Senegal migrant town Tambacounda mourns its lost sons

- Published

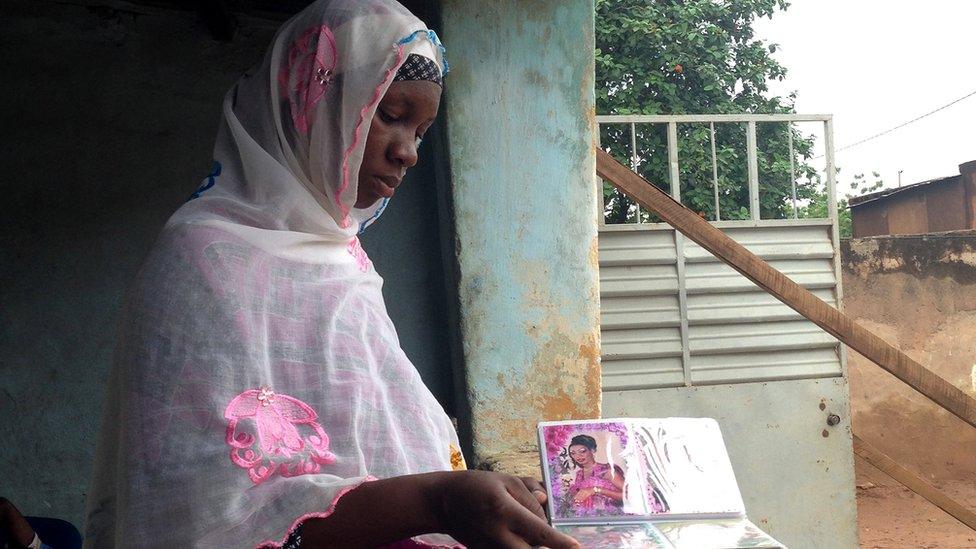

Aissatou Sanogo is looking after three children following her husband's death

People in one of Senegal's poorest areas are in mourning after dozens of their loved ones lost their lives in shipwrecks off the Libyan coast as they tried to make the treacherous journey to Europe. The BBC's Laeila Adjovi visited them.

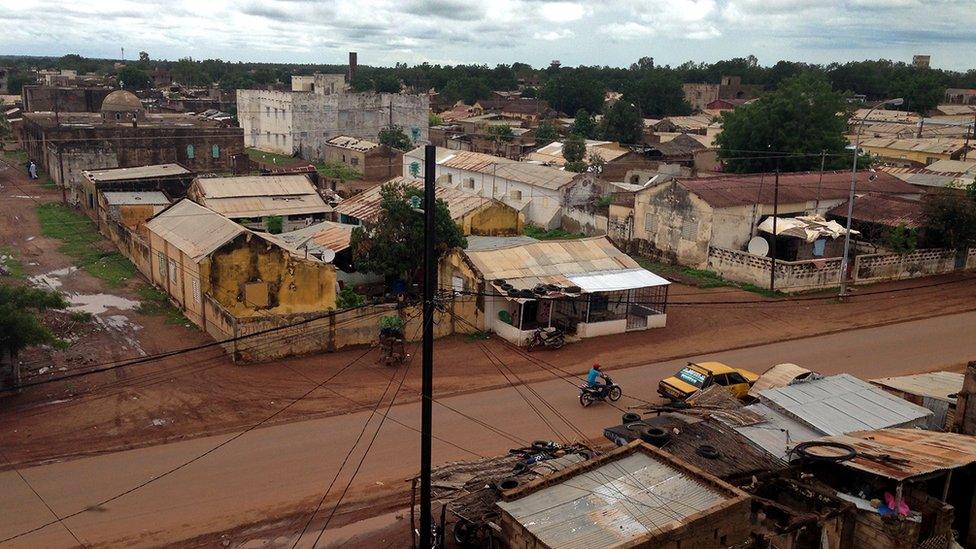

In the main city of Tambacounda in Senegal's eastern region, the main bus terminal is hardly ever empty. Located 600km (370 miles) east of the capital Dakar, the impoverished region borders Mauritania, Mali, Guinea and The Gambia. Many of the region's residents go abroad to flee poverty.

Aissatou Sanogo's husband, Souleymane, was one of them. She is only 25 years old but her features are drawn. She is wearing the white veil of recent widows.

"He left on 6 November," she says. "He went to Bamako in Mali and spent five days there, then he went to Libya. He spent five months there, and on 18 April, he boarded a boat to Europe. The accident happened on 19 April. I heard he was in the hospital or with the Red Cross. But on 11 June, I was told my husband had drowned."

'Falling from trucks'

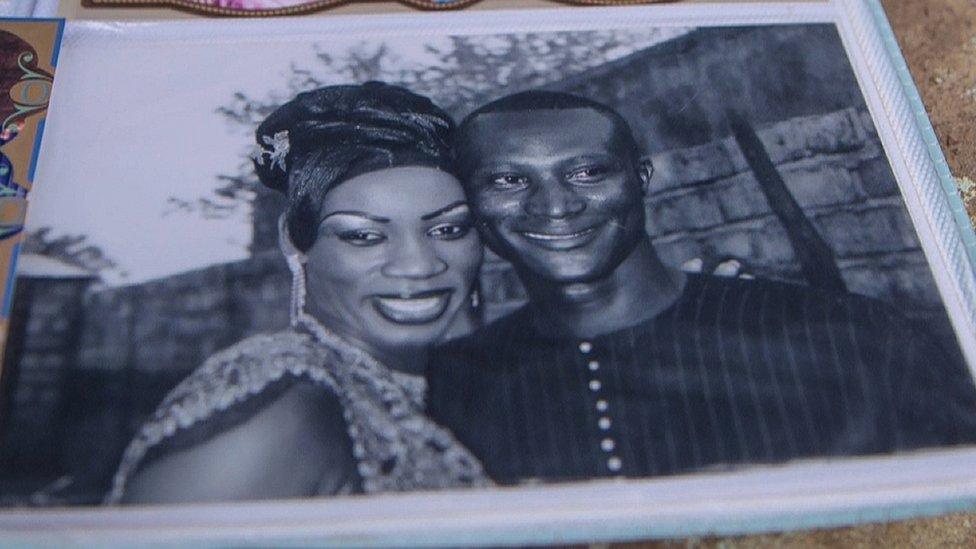

Mrs Sanogo shows pictures of their wedding and of the baptism of their three children, emphasizing the fact that she had not wanted her husband to leave his job delivering bread.

"I told him that I did not want him to go because I would much rather have my husband close to me," she said.

"I told him that even if we did not have a lot, he was earning some money and that I was not asking for much. But he insisted that he wanted to give us a better life, and not depend on anyone, and also provide for his sick father."

Mrs Sanogo says she did not want her husband to leave for Europe

Throughout Tambacounda, scores of people tell a similar story - a husband, father or brother who died trying to reach Europe illegally. Here, many travel agencies offer bus tickets to neighbouring countries.

From Tambacounda, most migrants go to Mali, and from there to Burkina Faso and then to Niger's northern town of Agadez, from where they travel across the Sahara desert into Libya. It is the last stop on land before people smugglers put them on boats towards Italy.

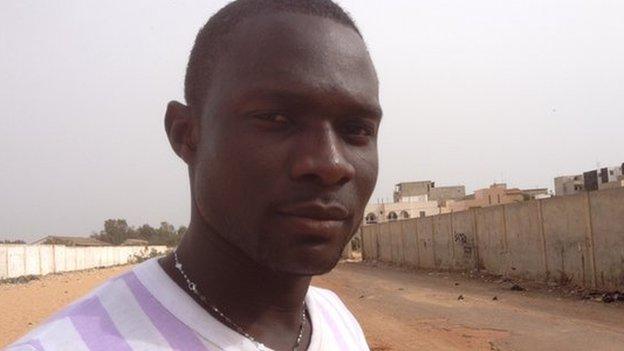

But many are unprepared for what happens on the way, says Aliou Mbow, 23: "Travelling conditions are so hard, even to get to Libya.

"You can get hit and sometimes people even get killed. For example, if there is an accident, or you fall from the truck in the desert and break your leg, the driver can pull out a gun and eliminate you, and then we keep on going. Nobody dares to ask for anything."

Mr Mbow made it to Libya but then there was some trouble on the boat to Italy. His group was lucky enough to be able to sail back to Libya.

He decided it was not worth risking his life again so he went back to Senegal.

Some local media have reported that in Senegal, the Tambacounda region has had the highest number of deaths since April due to illegal migration.

No jobs

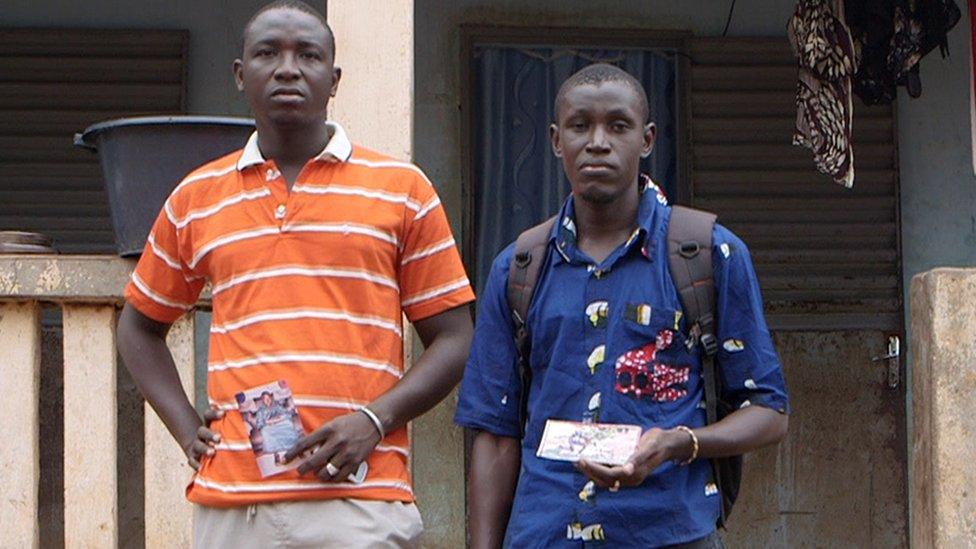

"Even after what happened in April, there are still people leaving," says Harouna Cisse, a teacher who has not had any news from his brother since he went on the perilous journey.

"Each day some young people take the trip, each and every day. This is because of unemployment. There is nothing here in Tambacounda, no infrastructure, and the government just keeps on making promises."

There is very little development in Tambacounda

Harouna Cisse (L) has not heard from his brother since he left for Europe

Expressing a similar view, Ibrahima Traore, the head of a youth group in Tambacounda, says: "Even if you graduate from a training programme you find no real economic prospect, no company to offer jobs here."

"Illegal migration is not a new phenomenon, but it is on the rise these past few years. And the government is just standing idly by."

There are still no statistics to evaluate the scale of the problem in a region where the official unemployment rate in 2013 stood at 36.5%, though some analysts say it is likely to be lower because it fails to take into account jobs in the informal sector.

The government wants people to become farmers to curb poverty

Bassirou Fall is a regional official from the ministry of youth. He cannot say how many have left or how many have died. He just knows how many made it back alive - 75 young men have been repatriated since the beginning of the year.

He admits the crisis is partly caused by "numerous failures in employment public policies".

"The profiles of returnees are young people from rural areas that were unemployed, or poor farmers," he says.

"According to their testimonies it is because they could not bear to see their parents struggle to provide for the family that they resorted to illegal migration. So we want to help them return to agriculture. We want to start vast and well-equipped farming structures to allow young people to work in them."

No-one knows exactly when those new farms will be set up. In the meantime, nothing is done for families who have lost their breadwinners to illegal migration.

Each day, the widowed Mrs Sanogo bathes her children in a small bucket in front of her house. She does not expect much from the government. The mother of three relies only on help from her poor family.

She could not prevent her husband from leaving but she has promised herself one thing: the only way one of her sons will travel to Europe will be on a plane, with a valid visa.

- Published13 May 2015

- Published19 February 2015