Will South Sudan peace deal be worth the wait?

- Published

South Sudan's President Salva Kiir signs the peace deal

They waited and they waited in the big tent adorned with chandeliers and fairy lights as the temperature gradually rose.

They have been waiting a while for peace in South Sudan, so weren't surprised to wait a few hours more for the nitty-gritty of an agreement to be ironed out before the show began.

The leader rarely photographed without his broad-rimmed trilby hat entered the tent with much acclaim, and finally put his name to South Sudan's latest hope for peace.

On the stage, five flags wafted in the breeze of a dozen fans. It was the combined weight of those flags which forced both leaders into submission.

Kenya, Ethiopia, Uganda and Sudan have been instrumental in bringing the two sides to the table.

And the people of South Sudan are sick of war.

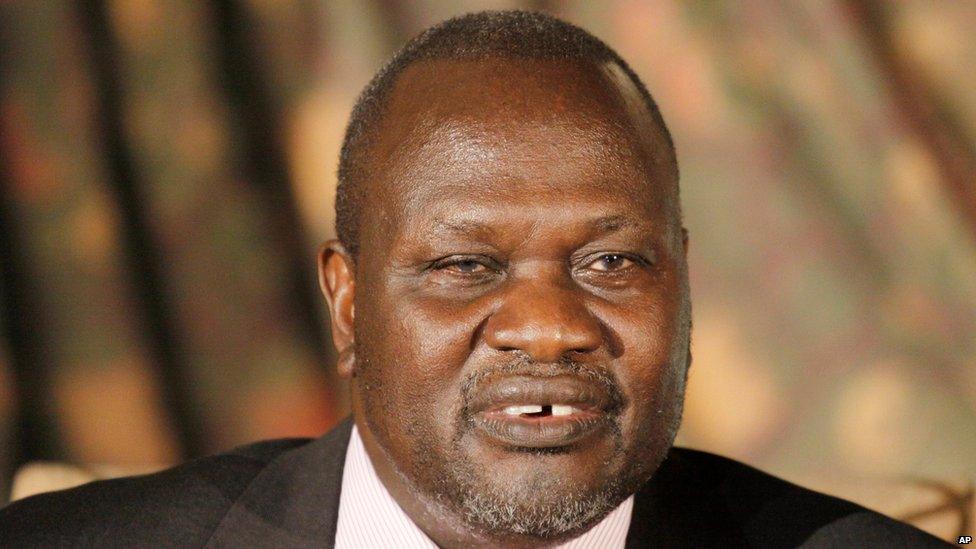

Rebel leader Riek Machar will become vice-president

South Sudan's President Salva Kiir had been given 15 days to sign on the dotted line after his rival, the vice-president turned rebel leader Riek Machar, agreed to terms set by an international panel of mediators last week.

'The wrong war in the wrong place'

A brass band dressed in red with a lavish gold trim added to the pomp and ceremony.

Each visiting head of state gave their comments in turn.

President Uhuru Kenyatta of Kenya hinted that the long day's discussions leading up to the ceremony had been hard, saying there's no such thing as "a perfect agreement", but it is better to find a solution around a table rather than on a battlefield.

"Don't see the obstacles," he said, "but the opportunity and hope."

The elder statesman, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, rebuked President Kiir, calling the fighting in South Sudan "the wrong war in the wrong place at the wrong time".

Up until the last minute it wasn't even certain if President Kiir was definitely going to sign, with his "registration of serious reservations."

Child soldiers have been used in the conflict

He even handed out photocopies of his list of reservations - and they weren't small points, but major differences.

He made a theatrical point of initialling a copy on every page - and unsuccessfully urging the other heads of state to do likewise - before finally putting ink to paper on the aptly called Compromise Peace Agreement.

'Will the fighting stop?'

But the question is not just whether the two leaders can even agree on a proper, long-lasting peace deal, but whether those fighting in the bush will take the cue.

At least with President Kiir's signature now on the peace accord there's more chance of an end to the fighting.

But don't expect the 200,000 people currently sheltering in UN camps to be heading home just yet.

There are still sporadic clashes, and with renegade generals splitting their troops from the rebel side and going it alone, it's hard to judge how successful a ceasefire might be.

The UN Security Council threatened "immediate action" if their members were left at the altar yet again.

America's draft resolution included targeted sanctions and an arms embargo.

A UN panel of experts said the free flow of weapons to both sides and the tens of millions of government dollars being spent on arms and ammunition were fuelling the war.

They also highlighted an increasing brutality towards civilians as rebel supporters were being cleared out of the countryside.

The statistics are horrifying - 1.6 million people have been displaced from their homes, 70% of the population are short of food including a quarter of a million severely malnourished children, and parts of the country have been cut off by fighting where aid workers can't go.

Twenty months into this crisis the reports of human rights abuses keep coming - child soldiers; rape as a weapon of war; ethnic-based killing; people being trapped in huts and burned alive.

There have been atrocities carried out by both sides, as the clashing of two political heavyweights and leaders of the country's two largest ethnic groups, sparked terrible violence.

There are parts of Unity state in the north of the country where aid agencies haven't been able to go, and where conditions are thought to be dire.

'Complex differences'

The complex historical differences between and within ethnic groups and clans will be hard to unravel.

And what the generals who have not signed up to peace decide to do with their thousands of troops will have a big impact on whether this really means peace.

The text of the agreement will be full of the loopholes and conditions necessary to bring the two sides together, but is unlikely to be a long-term solution.

The signing of the deal is just one small step in a long process towards peace and reconciliation - and there have been many steps this way which have faltered before.