Why does South Sudan matter so much to the US?

- Published

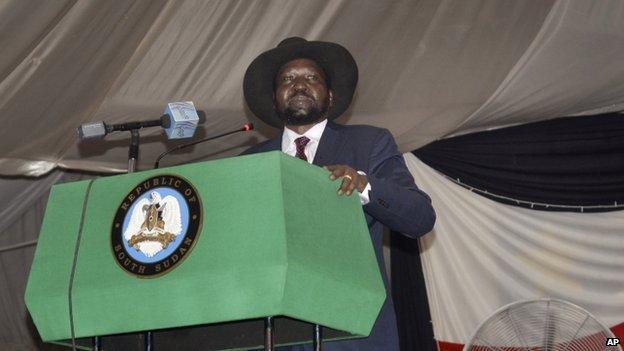

It wasn't so much a collective sigh of relief when President Salva Kiir finally signed the peace deal this week. It was more a sense of "let's see" as the US issued a warning that it would "hold to account" any of the leaders who might stray from their public commitment.

For the moment, the champagne is being kept on ice.

After more than a year and a half of hostilities and failed peace efforts, threats of sanctions and possible war crimes charges by the US followed.

President Obama has been left feeling deeply unimpressed by the South Sudanese leadership. During his recent East Africa visit there was talk of a "Plan B", external if the two parties failed to sign a deal.

A deadline was set and when Salva Kiir stalled and called for more time, Washington deployed its National Security Advisor Susan Rice for some straight talking.

She ditched the diplomatic niceties and singled out the South Sudan president, declaring Washington "deeply disappointed" that he had "squandered" the opportunity to bring peace.

A week or so earlier she delivered another salvo, warning that the leadership was putting its own selfish interests ahead of the nation. Although the US has been deeply frustrated at the impasse, it's clear that it had no plans to simply walk away.

So why does the US care so deeply about South Sudan?

Key points of peace deal:

Fighting to stop immediately. Soldiers to be confined to barracks in 30 days, foreign forces to leave within 45 days, and child soldiers and prisoners of war freed

All military forces to leave the capital, Juba, to be replaced by unspecified "guard forces" and Joint Integrated Police

Rebels get post of "first vice-president"

Transitional government of national unity to take office in 90 days and govern for 30 months

Elections to be held 60 days before end of transitional government's mandate

Commission for Truth, Reconciliation and Healing to investigate human rights violations

History

The US in general and President Obama in particular, have been looking for a "success story" in Africa. There are of course millions of individual success stories but collectively, like so many other global leaders, they thought they had it when on 9 July 2011 South Sudan became the world's newest state.

But secession from Sudan and the government in Khartoum was not a magic bullet.

Former Congressman Tom Andrews recalled to me from Washington how he had been in the town of Juba for the birth of South Sudan "literally going to sleep in one country and waking up in another without moving".

That sense of optimism was quickly replaced by a mood of "despair" felt by many ordinary citizens. America had a "special relationship" with the country and so felt a "special responsibility" to help.

You don't have to dig too deep back in history to find American footprints here. I remember a bitter cold night in 2004 huddled from the wind on the shores of Lake Naivasha in Kenya, covering my first ever story in East Africa.

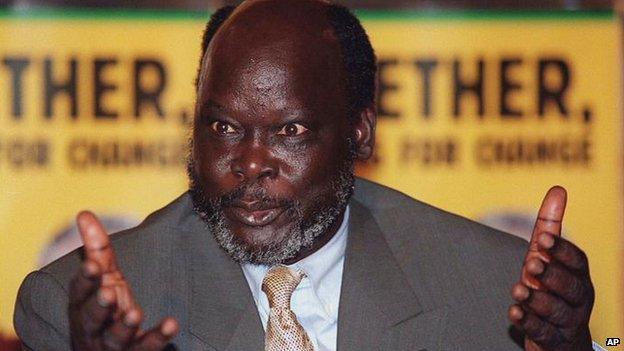

John Garang led the Sudan People's Liberation Army from 1983 to 2005

Peace talks were going on late into the night and the towering figure centre stage was John Garang, the leader of the Sudanese rebel movement, the SPLA. He was quietly admired by the American diplomats, shivering alongside us in the cold.

For years the armed militants had been fighting for independence from the north. Garang stood proud through a lengthy signing ceremony in the middle of the night. The documents that bore his name would later become part of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement. It was the deal which would seal South Sudan's independence.

John Garang's face now adorns South Sudanese bank notes

Turned on themselves

At the time the SPLA was considered a relatively cohesive liberation movement, fighting to break away from a country whose borders seemed to have been drawn up on the back of an envelope by the colonial administration forcing the largely Christian animist south to live alongside the Muslim, largely Arabic speaking north.

A year later John Garang would be dead, killed in a mysterious helicopter crash. He would never see an independent South Sudan.

A decade later the leaders who followed in his wake have turned political animosities into an all-out rebellion, where tens of thousands of civilians have been killed and 2.2 million people have been forced to flee their homes.

No longer facing a common enemy as they had done in the fight for independence, they turned on themselves in a conflict tinged with ethnic rivalries. Millions more are hungry and the US has been largely left to pick up the bill.

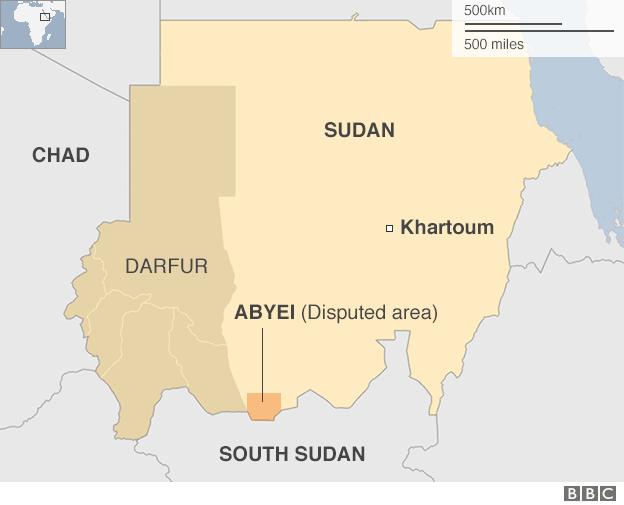

The north of the country was largely (although not exclusively) Muslim and Arabic speaking, occupying about two-thirds of the land mass. In contrast, the South took its reference points for its race, culture and religion from the rest of sub-Saharan Africa.

After independence in 1956, the "northern-dominated government in Khartoum sought to Arabise and Islamicise the South", explains Francis Deng, a Sudanese academic.

The reaction was to trigger Christian evangelists, largely from the US, to come to Sudan and spread throughout the south to counter the Arab-Muslim model of the north.

Fast forward to today and the the world's newest state has been engaged in what the Royal Africa Society's Richard Dowden says is "the worst war in Africa at the moment". With its historical footprint, he argues, America feels "responsible".

Strategic influence

The US spent $1.2bn (£780m) in South Sudan last year. More than half of that was emergency relief.

Even before it seceded from the north, oil-rich Sudan was a top priority for America. According to the US official development assistance database, Sudan has been the third largest recipient of its aid since 2005, behind only Iraq and Afghanistan.

There's also a broad agreement among many who pay attention to this part of the world that global leaders underestimated the complex inter-relationship between the conflict in Darfur in the west of Sudan and the wider struggles between north and south.

As the spotlight was shone on Darfur - a Muslim-on-Muslim war fuelled by competition for scarce resources such as water - for which President Omar al-Bashir has been indicted by the International Criminal Court, the potential conflicts between north and south were somewhat overshadowed.

News can only deal with one Sudan crisis at a time, a news colleague joked at the time. He was right.

The reality is that some of the players from the Darfur conflict have been implicated in South Sudan's more recent war. Regional neighbours have used it to settle old scores and the US, which heavily backed the South's bid for independence, feels quite possibly let down, almost embarrassed by it all.

Prof Calestous Juma, a Kenyan-born international development specialist at Harvard University, makes a further point. He says that South Sudan is "now at a new geopolitical competition between the US and China, with ethnicity fanning the flames of a political fire created by the volatile mix of religion and oil".

If you agree with that then it's clear the US cannot afford to ignore South Sudan.

Political lobbying

Three successive US presidents have been pushed to make Sudan a foreign policy priority.

In the early 1990s the US granted military support to neighbouring countries to stem the advance of the Sudanese military. In 1993 Sudan was declared a state sponsor of terrorism and faced the imposition of sanctions.

And from the crisis in Darfur sprang a bi-partisan movement - the Save Darfur campaign - which was arguably a huge success in putting this patch of the globe, thousands of miles away from the White House, on to TV screens across the US, declaring it a modern day "genocide" .

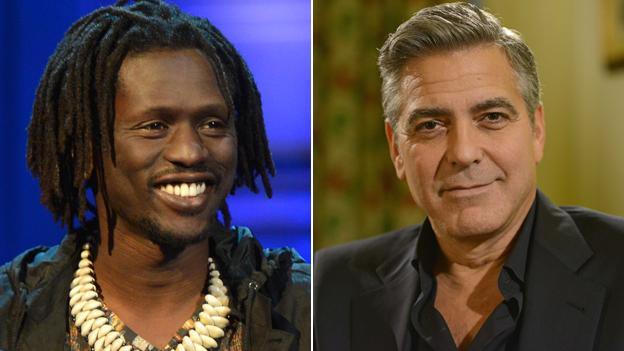

Sudan activists include South Sudanese musician and former child soldier Emmanuel Jal and actor George Clooney

One of the movement's founding members was Senator Barack Obama, so he has a very personal reason for caring about South Sudan.

Since then influential figures including the former Director for African Affairs at the National Security Council, John Prendergast, has founded the Enough Project to end genocide.

Driven by humanitarian concerns they have helped to keep the issue alive. Not to mention popular stars such as the actor George Clooney, and ex-Sudanese child soldier Emmanuel Jal, who have acted as goodwill ambassadors for a number of UN agencies working on Sudan and South Sudan.

Tying up loose ends

In the same way that the US has recently moved to "normalise" relations with Iran, much has been made of a "rapprochement" with Khartoum in recent months.

A recent piece in the Sudan Tribune, external sheds some light on the behind-the-scenes movements to try to rebuild bilateral ties between Washington and Khartoum, as part of a policy driven by intelligence concerns.

It is perhaps naive (though not inconceivable) to imagine that the US will fully embrace a country whose leader is the subject of an arrest warrant by the International Criminal Court.

It is unlikely to happen in the remaining time Barack Obama has as president.

But Washington's strong rhetoric against the leadership of South Sudan, should it renege on its promises, sends an important message to its northern neighbour. That despite its history and the US backing for the South's drive for independence, it is not beyond reproach.