Mozambique leads way on tackling menace of mines

- Published

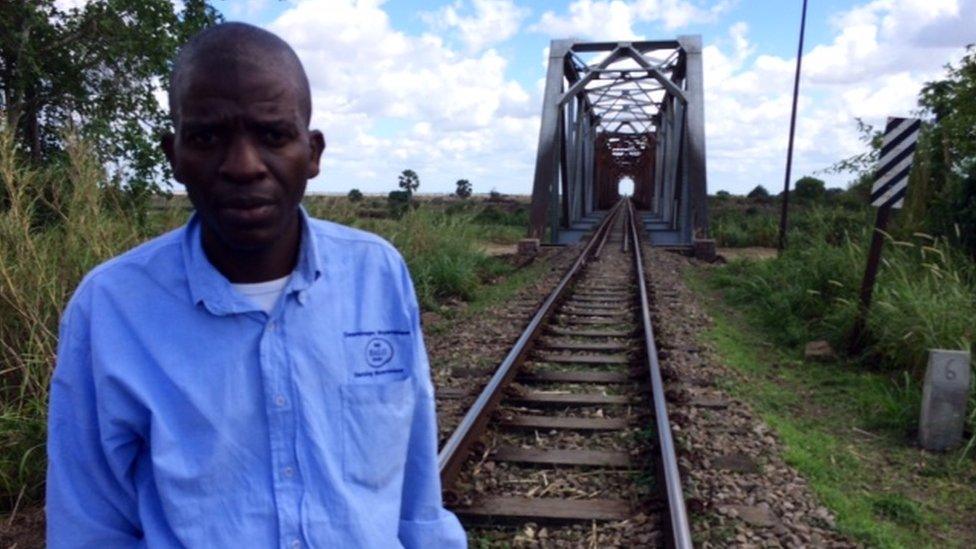

Joao Maximal has worked for years to clear Mozambique of mines

Joao Madamol was just 11 years old when he witnessed the sheer terror and insanely random nature of anti-personnel mines.

"I saw a woman in a field being carried off on a stretcher with her leg blown off," he says.

One of the men trailing behind was carrying a fragment of what he would learn later was an anti-personnel mine.

Trying to ensure others did not face the same pain and misery would become his life's work.

As a young Mozambican growing up during the civil war in the late 70s and early 80s, Joao saw first hand how his country, like many others at the time, found itself embroiled in the enmities of the Cold War, fuelling its own internal conflicts.

As he trained as a de-miner, it was no surprise to come across mines from the US, China, Russia, Hungary and Portugal littered in strategic positions to either protect infrastructure and key installations or deny territory to the "enemy".

Joao describes in graphic detail the first time he identified a mine.

It was about 08:00 and he picked up a signal from his metal detector under one of the many bridges heavily fortified in the north of the country.

"I was about to cry, I was so terrified," he says.

It was a time when some 600 casualties a year were being reported as a result of landmines in Mozambique.

That figure dipped down to just over a dozen in the last years of mine clearance.

Two decades later, Joao's tears are now of relief that the last known anti-personnel mine has been removed from Mozambican soil and his children can grow up in a mine-free land.

So what are the lessons Mozambique can offer to the world?

Mines were found under this abandoned railway carriage

The first lesson is that "it is possible to clear a whole country", according to Calvin Ruysen, head of Africa for the Halo Trust, external. "The second is coordination," he adds.

Dr Alberto Augusto, the director of Mozambique's National Institute for De-mining, agrees it is undoubtedly the coordination between the government and the humanitarian operators and the commitment to get the job done that has enabled Mozambique to achieve mine-free status.

The way the government and its partners "deal with communities living with mines around them" is also critical, he says.

Organisations such as the Halo Trust, which have been responsible for 80% of mine clearance in Mozambique, have trained and employed thousands of de-miners from the very communities affected.

It more or less guarantees huge buy-in and an enduring incentive to recover roads, dams and fields, contaminated by landmines and re-engage them in productive activity.

Ottawa convention

Some 162 states globally have signed the Mine Ban Treaty, external known as the Ottawa convention on the prohibition and destruction of anti-personnel mines, which came into force in 1999.

It is a commitment to destroy all stockpiles and work to clear sites contaminated by mines.

Non-signatories to the Mine Ban Treaty:

Armenia; Azerbaijan; Bahrain; Burma; China; Cuba; Egypt; Micronesia; Georgia; India; Iran; Israel; Kazakhstan; North Korea; South Korea; Kyrgyzstan; Laos; Lebanon; Libya; Mongolia; Morocco; Nepal; Pakistan; Russia; Saudi Arabia; Singapore; Sri Lanka; Syria; Tonga; UAE; US; Uzbekistan; Vietnam

Mozambique signed the treaty at the outset but, like many other states, found a 10-year commitment unrealistic and had to request extensions to several deadlines in order to complete its work.

Like Mozambique, many countries are emerging from conflict and need to build transitional governments from scratch before they can begin the gritty task of removing mines from the ground.

The most heavily mined areas on the planet in terms of land mass, remain Afghanistan, Bosnia, Cambodia and Turkey and "very probably Iraq", which are classified as having "massive anti-personnel mine contamination", according to data from the Landmine Monitor, external.

Mines are still manufactured but in much smaller quantities than before the mine-ban treaty came into existence.

Last year saw a dramatic milestone when the US was removed from the list of mine producing countries.

The Landmine Monitor believes "active production", external may be on-going in as many as four countries: India, Myanmar, Pakistan and South Korea.

Much to do

Mines may have been cleared from Mozambique, but there is still work to be done.

Just across the border in Zimbabwe, where many Mozambicans regularly travel to trade, there remains a thick belt of anti-personnel mines.

Rats have been used to sniff out landmines in parts of Mozambique by some other de-mining operators

Accidents caused by unexploded bombs also continue, with a number of child casualties reported just a few weeks ago, and the Halo Trust is now in discussions with the government of Mozambique about clearing former military ammunition depots, according to Mr Ruysen.

In countries such as Afghanistan, where old Soviet mines continue to litter the countryside, you quickly discover that the world for "mine" and "roadside bomb" are used interchangeably by civilians and the Afghan National Security Forces, causing considerable confusion.

As landmine production and contamination wane and armed militias employ more guerrilla-style tactics, using trip wires, booby traps and roadside bombs detonated by mobile phones to intimidate, maim and kill, the type of help conflict countries require is changing.

Assistance and training in clearing these types of deadly weapons are likely to eventually become the mainstay of mine-clearing charities' activities.

And as conflicts continue in Syria, Iraq, Central and South Asia, de-miners are unlikely to be done out of a job.

- Published17 September 2015

- Published27 June 2014