Why I cannot tell 'the African story'

- Published

Great-grandmother Marie carries her adopted great-grandson Donnell Junior, whose mother died from Ebola

Ugandan TV journalist Nancy Kacungira has won the first BBC World News Komla Dumor Award for Africa-based journalists. Here, she explains her dilemma when she is asked to tell "the African story".

What comes to your mind when you think of "the African story"? Is it poverty, war and disease?

It is commonly accepted that journalism is mostly about bad news - planes landing successfully are not news, but plane crashes are.

In the case of Africa the focus on things going wrong is particularly harmful because of the relative dearth of other widely accessible sources of knowledge about the continent.

The system of storytelling on Africa is too often incomplete, stereotyped - and specious.

For example, reports on conflict in some African countries seem to give the impression that all of Africa is at perpetual war.

Yet no-one would associate the violence in East Timor, Syria, Sri Lanka and elsewhere with Asia as a whole.

Media reporting on Africa rarely focuses on everyday matters or the curiosities of daily life.

The result is an idea that the African crisis is "normal" - and any "good news" about the continent is an exception to the rule.

This narrative needs changing, and there have been numerous calls for more journalists especially from Africa, to tell "the African story".

2,000 languages

I am a journalist from Africa. I have lived and worked in Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya, and have an intimate relationship with the East African region.

But I cannot tell "the African story".

African countries share some similarities, for sure.

But when reporting on the political, economic and socio-cultural fabric of Africa, lumping all 54 countries into a single category just doesn't cut it.

More than a billion people live in Africa. There are more than 3,000 distinct ethnic groups; more than 2,000 languages are spoken.

It's a huge continent: the US, China, India, Europe and Japan combined could all fit into Africa.

So what could possibly inform a collective identity for such a vast and diverse part of our world?

Historically, much of the African identity has been not so much about what we are, but what we are not.

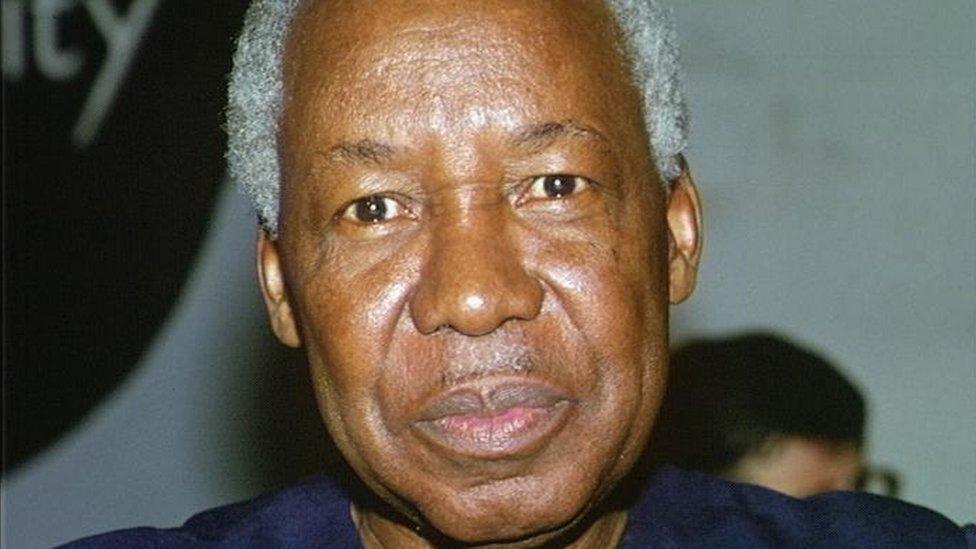

Julius Nyerere defined Africans as one people in relation to Europe

As Mwalimu Julius Nyerere put it: "Africans all over the continent, without a word being spoken either from one individual to another, or from one country to another, looked at the European, looked at one another, and knew that in relation to the European they were one."

Perhaps this is the crux of the problem: Africa continues to be defined as a country because it is always being compared to something from the outside.

Maybe that is why we call it either the "Dark Continent" or the "Rising Continent"?

Complicit

To define Africa as a whole makes it necessary to look at it from the outside.

But constantly doing so results in tropes that undermine the perspectives of those that live on the continent.

Rather than "the African story" there are very many African stories, and what I can do, as a journalist, is to tell some of them.

Journalists from every corner of the continent need to do the same. But African journalists will not always tell the best stories just because they are African.

Many African news outlets rely on foreign/western-based international news agencies to tell stories about other African countries - and become complicit in spreading misleading dominant narratives.

Hotel bookings are down in Tanzania because of the Ebola outbreak thousands of miles away in West Africa

An African journalist who parrots cookie-cutter storylines will not tell a better story than a foreigner who strives to understand context and nuance.

But what is needed now, more than ever, is a multiplicity of stories from within to challenge the dominant narratives from without.

Reliance on a dominant external narrative is not just a philosophical issue: it can have very tangible effects.

Geographical ignorance

Donald Kaberuka, former President of the African Development Bank, recently told a think tank in Beijing, external it "had become necessary to ensure that potential business opportunities in African countries are not jeopardised by a single story line whereby negative issues in one country are attributed to all 54 countries on the continent".

Look at the Ebola epidemic which hit Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia: the World Bank estimates, external the outbreak has cost other countries in sub-Saharan Africa more than $500m (£320m) in 2015.

It blames ignorance, external of African geography. For instance, the Hotels Association of Tanzania said that advance bookings for 2015 were 50% lower, external.

This in spite of the fact that Rome and Madrid are closer to the centre of the Ebola outbreak than Tanzania, which unlike Spain has never had a single case of the disease.

It is simply impossible to define Africa with just one description.

Addis Ababa, capital of Ethiopia - one of the world's 10 fastest growing economies

In Africa you'll find Ethiopia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ivory Coast and Mozambique - four of the world's 10 fastest growing economies.

You'll also find some of the world's poorest countries.

You'll find Equatorial Guinea with a 94% literacy rate (the global average is 84.1%) and South Sudan with a 27% literacy rate.

You'll come across local inventions like:

A touch screen medical tablet, external that enables heart examinations in remote locations

High-tech electric pedicabs, external manufactured from recycled materials

Stickers, external that turn any surface into touch sensors or screens.

But you will also discover that female genital mutilation occurs in 27 African countries and in Tanzania people with albinism are at risk of being attacked and mutilated by those wanting to use their body parts for witchcraft.

African countries by GDP ($bn):

Five largest:

Nigeria: 568.5

South Africa: 349.8

Egypt: 286.5

Algeria: 214.1

Angola: 131.4

Five smallest:

Seychelles: 1.4

Guinea-Bissau: 1.0

The Gambia: 0.8

Comoros: 0.6

Sao Tome and Príncipe: 0.3

Source: World Bank, 2014

Africa is not rich or poor, educated or illiterate, progressive or archaic.

What Africa is depends on which part of it you are referring to.

No single story can adequately reflect that, but a multiplicity of stories can and should broaden our received wisdom about the continent.

With more platforms and opportunities than ever before, there has never been a better time to challenge that confusing and costly concept of a single African story.

- Published18 October 2015

- Published21 October 2015

- Published23 September 2015

- Published19 October 2015

- Published19 October 2015