Why election results in Africa are so slow

- Published

Sunday was a busy day for elections around the world. Results from Argentina, Guatemala and Poland were announced within hours, but election officials say results from Tanzania, Ivory Coast and the Congo referendum will take several days.

Everyone hates a slow election process.

It's not just the voters and the candidates, desperate to know the results.

It's also the election staff, who probably got up before dawn to prepare the polling station, worked all day running the voting, stayed up most of the night counting the ballots and then had to take the results to a central point and wait for hours, sometimes days, to see their results safely received and entered into the system.

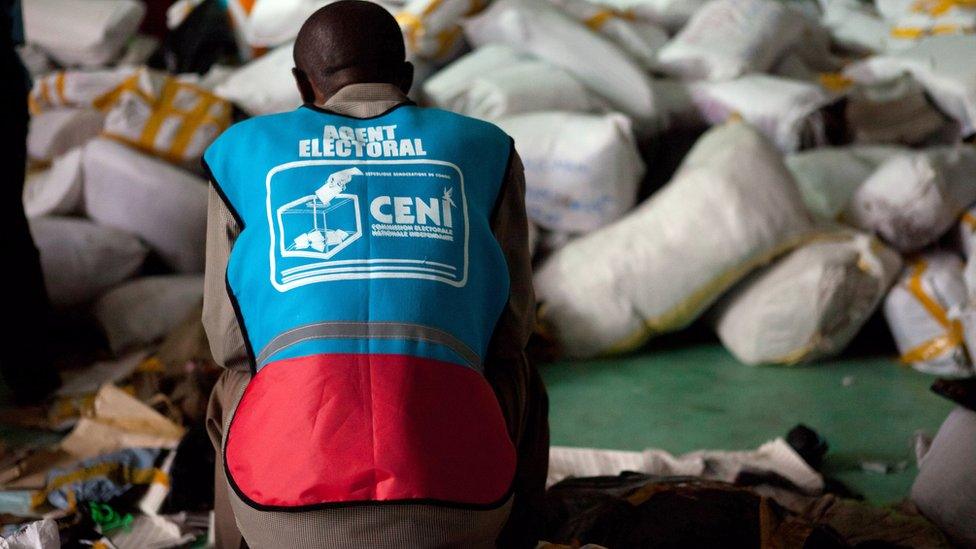

In the Democratic Republic of Congo capital Kinshasa in 2011, I remember presiding officers at the tally centre, fast asleep on top of their sacks of ballot papers; in Nigeria the same year, I watched as the Edo state election commissioner, red-eyed and grey with fatigue, waited for the last results - carried by canoe and motor boat - to finally arrive from the creeks of the Niger Delta.

Presidentially slow

The problem is not a lack of technology.

The UK still uses the most primitive of voting systems - paper ballots, physically carried to the counting centre and counted by hand.

But the UK, like Poland, which voted at the weekend, and India, the biggest democracy of all, has a big advantage.

It takes longer to count votes for a president than for a parliament

It's a parliamentary system, so the election in each constituency is complete in itself and can be declared immediately; there is no need to wait for results from the whole country to know who the next president will be.

Apart from Ethiopia, most African countries have presidential systems, and these are inevitably slower.

Fears of fraud

The other advantage the UK has is one of trust.

Where there has been very little past fraud, there is no need for time-consuming safeguards.

Polling officials could simply phone their result in to the national election commission, and no-one would doubt them. But unhappily that is not the case in most of Africa.

The Edo State results had to be brought physically to Benin City so that the commissioner could see that the results sheets had not been altered and all the party agents had signed that they were correct.

And the commissioner then had to get on a plane and personally fly to the capital, Abuja, carrying the State results sheets (again, signed by all parties) to the national election headquarters.

No wonder the process takes time.

And physically transporting results is not foolproof.

Sometimes the results which arrive are not the same as those which left.

People fear that votes can be manipulated

In the DR Congo, the European Union noted that the results its observers had seen in Katanga province were not the same as those later declared in Kinshasa.

So that's why conscientious officials slept on top of their ballot papers.

Attempts to speed up the process with modern technology have not been a great success.

Malawi bought a sophisticated electronic transmission system for its elections last year, but it was so sophisticated that most districts could not get it to work.

The fax system used as a back-up collapsed under the strain, and in the end, after days of delay, the results were hand-carried to the national headquarters.

India's electronic voting machines make counting relatively fast

Where machines are used, the best systems have been the simplest.

India uses small voting machines, powered by batteries. They are not connected to phone lines or the internet.

They simply keep a record of the votes cast, locked inside, and are safely stored until the time comes to count.

Indian elections are so huge that voting days in different areas are spread over several weeks, but the count itself goes quickly.

In Malawi rumours of manipulation were rife, and this is the problem when results are delayed.

Phoning it in

Mobile phones have been a game-changer.

Political parties and and local observer groups can now run their own parallel counts.

Because they trust their agents, local results are simply phoned in to the national headquarters.

Typically these parties and civil society organisations know the election result long before it is officially declared.

This can be an effective check on fraud, but where people think they already know the result, yet there is no declaration, they get suspicious.

Even where there is a ban on declaring these unofficial results, eventually they begin to leak out.

Transporting votes, as in Tanzania, because people fear fraud, slows the count down

Of course, sometimes the results are being massaged, but even where they aren't, trust is undermined.

Yes, logistics in Africa are challenging and communications are unreliable, but above all it is the need for multiple layers of safeguards which makes these election processes cumbersome.

But until everyone is prepared to trust a simpler system, African voters will just have to keep waiting, and waiting, for their results.

More on elections across Africa

Elizabeth Blunt has reported on African elections since 1979, and has also served as an election observer for the Commonwealth and the European Union.