Living under a shadow of fear in Central African Republic

- Published

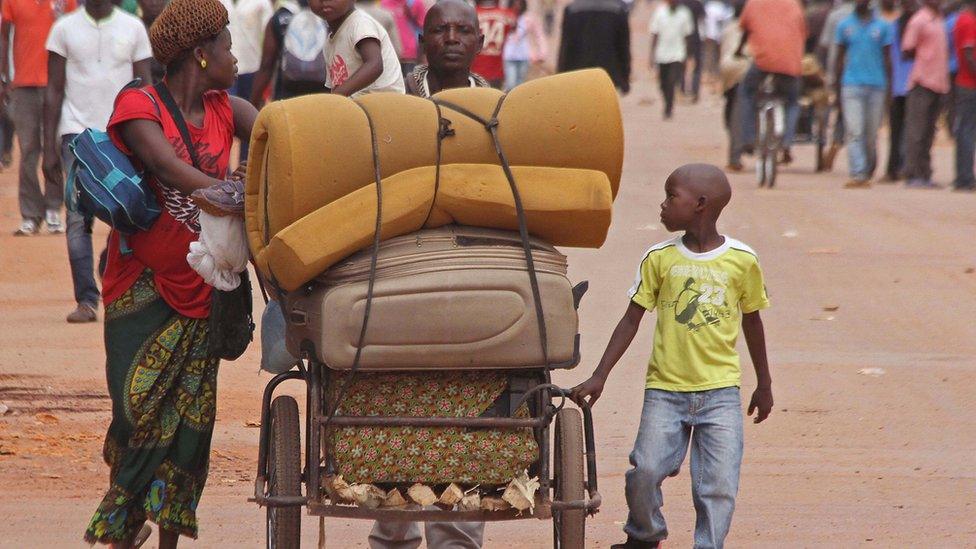

Some Bangui residents still do not feel safe in their homes and seek refuge in nearby camps

Working days start early in Bangui, capital of the Central African Republic, and they end early too because of a dusk-to-dawn curfew.

The country has been in turmoil since a loose alliance of mainly Muslim rebel groups, operating under the name Seleka, left their strongholds in the north and marched south and seized power in March 2013 from then-President Francois Bozize.

Their main leader, Michel Djotodia, briefly took over before being replaced by an interim head of state.

Since then, the CAR has lived under a shadow of fear, uncertainty and violence which has left some 6,000 people dead.

And the unrest has not gone away, far from it.

As we arrived in the capital, we were told that several people we had agreed to meet in the centre of town would not be able to make it.

It just was not safe anymore, they told us.

Three Seleka officials had been abducted and had disappeared; their bodies still have not been found.

The tit-for-tat response was immediate. The following day, three Muslims were killed. An accusing finger is being pointed at the mainly Christian "anti-balaka" vigilante militias.

Ingrid Sandanga is one of the presenters on Radio Ndeke Luka

News of the latest killings was broadcast for everyone to hear on Radio Ndeke Luka, one of the most listened to radio stations in the CAR.

Even the journalists there have had to adapt to the changing situation, with staff getting in to work later and leaving earlier because of the insecurity in Bangui.

"It's a small price for us to pay if we want to continue reporting on events," the morning show presenter, Ingrid Sandanga, told me.

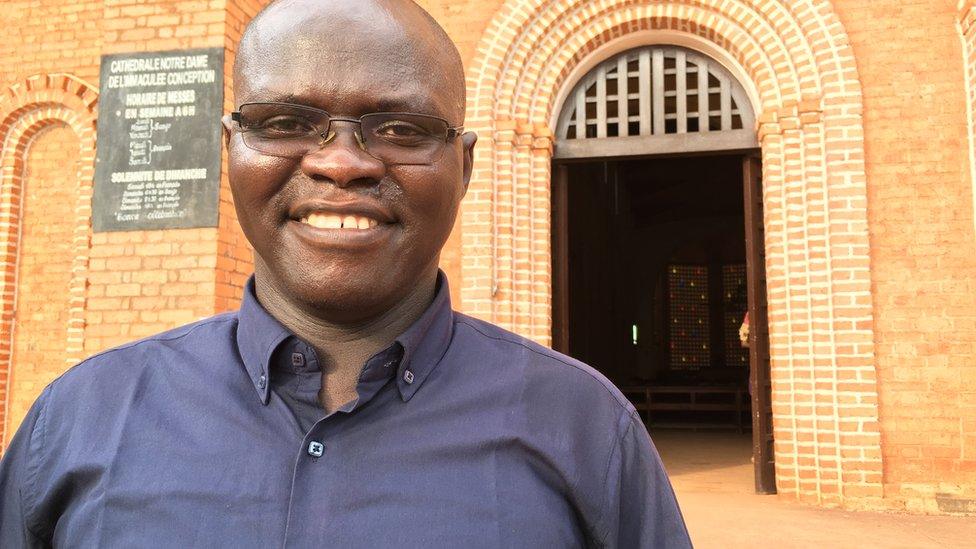

Father Xyste Mbredjeze-Ngasha is trying to build bridges between divided communities

And she points to a large, plastic-covered, sign on the table - the station's mission statement: "Ensemble, combattons la division dans notre pays", meaning "Together, let us fight division in our country".

Religious leaders are at the forefront of reconciliation efforts, with representatives of different faiths working hand in hand.

One of them is imam Abdoulaye Ouasselegue, vice-president of the CAR's Islamic Council.

As if to highlight what he is trying to achieve, he made a point of meeting us not at his mosque but on the grounds of Bangui's Catholic archdiocese, an island of tranquillity on the banks of the Ubangi River.

He is hopeful that stability will return, but says that he no longer wears anything that may identify him as a Muslim because it is too risky.

CAR's religious make-up

Population: 4.6 million

Christians - 50%

Muslims - 15%

Indigenous beliefs - 35%

Source: Index Mundi, external

When asked about the importance of the international military presence in the country under the flags of the UN and France, he lets out a long sigh of resignation, before answering: "What's the point of having peacekeepers here if there is no peace to keep?"

Father Xyste Mbredjeze-Ngasha is also hoping to build bridges.

But this Catholic priest faces a huge task - he has just been put in a charge of a new parish in PK5, Bangui's now notorious fifth district.

Home to many of the capital's Muslims, it has become a flashpoint in the current conflict.

The first time Father Xyste entered a Muslim neighbourhood in his parish, he had to be escorted by armed UN peacekeepers.

"I fear for my safety, but I must do God's work," he says.

'I don't feel safe'

As the afternoon begins to draw to a close, anxious Bangui residents head for home.

But for some, beating the curfew is the last thing on their minds.

They have no homes to go to. They are the thousands of people living in the capital's 28 camps for the displaced.

Keeping the peace in CAR

French troops are briefed before going out on patrol in Bangui

A 10,000-strong UN force took over a peacekeeping mission in September 2014

France has about 2,000 troops in its ex-colony, first deployed in December 2013

At the Benzvi camp, half of the tarpaulin tents are in bad need of repair, there is little sanitation, limited access to clean water and the camp becomes a quagmire of mud with each heavy rainfall.

A few months ago, the aid agency Medecins Sans Frontieres, who provide much-needed medical assistance and food relief there, were hoping to close it down.

But then violence broke out again in September and terrified Christians rushed to the camp.

More than 2,500 people survive in dire and cramped conditions, too afraid to venture beyond the camp's gates.

People in the camps try to earn a living, selling food to other residents

"Even here, I don't feel safe, I'm scared that the Seleka fighters will attack us again," one young woman now living in Benzvi told me, echoing the thoughts of many.

With peace still a long way off, the transitional government led by the interim President, Catherine Samba-Panza, is pressing ahead with plans to hold elections.

They have already been postponed once.

But President Samba-Panza still hopes to see the country go to the polls before 31 December, when her mandate expires.

' Elections will happen this year ' - C A R interim President

"We have no other choice - our priority is to secure the electoral process," she says.

"When the time comes, we shall see if we are really able to go ahead."

As the president speaks, Rwandan soldiers from the UN's Minusca, external force look on.

They have been tasked with guarding the presidential compound.

It is a sobering reminder that security in the CAR cannot be guaranteed without outside help.

Julian Keane will be presenting Newsday from Bangui on Friday 30 October 2015 from 06:00 GMT to 08:30 GMT on the BBC World Service.