The tough task of leading Libya’s peace talks

- Published

This month, the United Nations outgoing envoy to Libya, Bernardino Leon, found himself under a cloud of controversy when it was revealed he would soon be taking up a job in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). His newly appointed successor will have to contend with a lot of trust issues.

Bernardino Leon has been appointed by the UAE to lead the country's Diplomatic Academy. He had been in talks with the Gulf state's foreign office for several months about this new role - a deal that appeared to be finalised last week.

The UAE is widely seen as a party to the regional proxy war in Libya, often accused of financially and militarily supporting one side of the country's civil conflict, which it denies. Mr Leon was leading the political dialogue between Libya's warring political factions and parallel parliaments.

Last week, the Guardian revealed details, external that included diplomatic promises Mr Leon appeared to make in private emails to the UAE's foreign minister as far back as December.

Whichever angle you look at it from, it looks bad. It is ultimately embarrassing for the UN, and it is damaging to its mission to Libya.

Mr Leon denied any conflict of interest and that his proposed political agreement for Libya had ever been biased, saying he probably made the same promises to other regional players. Perhaps he did, but none of the others was simultaneously offering him a high-paying job.

UN diplomats in New York largely tiptoed around questions put to them over the matter, by simply saying they fully supported the UN mission to Libya and the work Mr Leon had done.

Into the storm

Mr Leon is leaving behind a process that remains deadlocked over his proposed "final political agreement", which includes a new unity government for Libya.

Bernardino Leon denies his proposed political agreement for Libya was biased

As Mr Leon prepares to exit, his successor as Libya's UN envoy, Martin Kobler, is walking into a storm left behind in the UN mission that is threatening to destroy a year-long political process.

He has quite the unenviable task ahead of him.

He is an experienced diplomat used to a hands-on approach and leading peacekeeping missions on the ground.

He has served in some of the world's toughest conflict zones, including Afghanistan and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Libya, however, with all its divisions and frequent shifting alliances, has left all foreign diplomats scratching their heads over the years.

So what lessons can be learnt?

If Mr Kobler is hoping for a modicum of success where all his predecessors have failed, he will need to employ a transparent and realistic approach to the largely disputed political agreement.

Mr Leon's proposed national unity government has sparked protests in Libya

At this time, most of those loudly cheering on the proposed unity government are foreign diplomats.

But Mr Leon says "the majority of Libyans" also back it.

Others supporting it include some Libyan actors in the dialogue rewarded with positions in the new government or who strongly believe they will be a part of it. Several militia groups are in the same boat., external This is hardly a foundation to build on.

Transparency is key. Too often during the dialogue, the delegates, who rarely ever sat in the same room together, were told what they wanted to hear.

At different times, each side would be left wide-eyed or angry after a press conference where Mr Leon would claim everyone was in agreement over everything and announce subtle changes.

According to insiders today, the UN Support Mission in Libya (Unsmil) is hoping to get enough MPs from each parliament to unilaterally back the political agreement and sign it.

This divide-and-conquer approach is a dangerous gamble in a political and military environment rife with divisions.

Libya's rival power bases

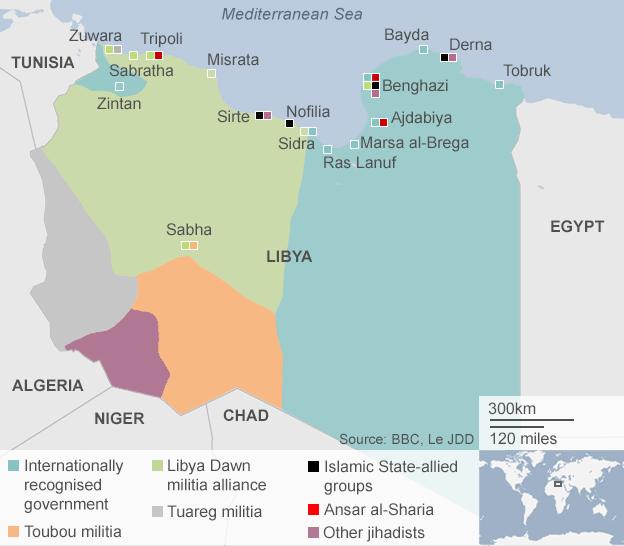

In the west, Islamist militias, including Libya Dawn and Libya Shield, control the capital, Tripoli, alongside the defunct parliament, the General National Congress (GNC).

Fighters from the jihadist group Islamic State (IS) have established a stronghold in the central coastal city of Sirte, encroached on nearby oil sites, and suffered some losses in their initial hub in the eastern city of Derna, for instance to the Derna Mujahideen Shura Council.

Other jihadist groups include Ansar al-Shari'ah, considered close to al-Qaeda, which is most prominent in eastern Libya, and the Benghazi Revolutionaries Shura Council, a coalition of Islamist militias (which includes Ansar al-Shari'ah).

In the east, groups supporting the recognised authorities are battling other Islamist militias, particularly in the country's second city of Benghazi, where battles have raged since early 2014.

The Al-Zintan, Al-Sawa'iq and Al-Qa'qa Battalions are anti-Islamist militias that support the official authorities and also operate in the west of Libya, for instance in the city of Zintan.

National reconciliation

The parameters that define which Libyan force will be entrusted with securing the country need to be identified and made clear by the UN to all the parties involved.

Ambiguous means to serve diplomatic ends are ultimately paving the way for continued militia rule.

The Libya Dawn Islamist group is just one of many militias in the country

Foreign states, including the US, UK and France, have repeatedly said that accountability for crimes committed by armed groups in Libya is key.

But it appears they are simultaneously pursuing a scenario in which rival militias will "protect" any new unity government.

They are banking on new militia alliances forming.

This is a formula that will cripple any new authority in the country.

Libya's numerous factions might also benefit from some breathing space to get together on their own.

They have done it before, and sporadically do it today.

If the international community invested more efforts in transforming locally brokered sticking-plaster resolutions into permanent ones, they might actually get somewhere.

Earlier this month, Tarek Al-Mitri, who led the UN mission to Libya when it was last operating from inside the country in 2014, told the Abu Dhabi Strategic Debate elections in Libya had been rushed and national reconciliation should be given priority.

It is an important point - even if he did little in the way of addressing this factor during his tenure.

The root of the country's post-Gaddafi troubles lies in the absence of national reconciliation, and justice for both the Gaddafi era and the aftermath.

Holding to account every militia leader and political figurehead backing them would be the start of a process of pinpointing which force will protect the new government.

But is anyone willing to address that elephant in the room?