After jihadists strike Burkina Faso and Mali, where next?

- Published

The attacks on a hotel and cafe in Burkina Faso killed 29 people

We will probably never know how long exactly it took for al-Qaeda militants to plan their attacks in Mali's capital Bamako as well as in Ouagadougou, the capital of Burkina Faso.

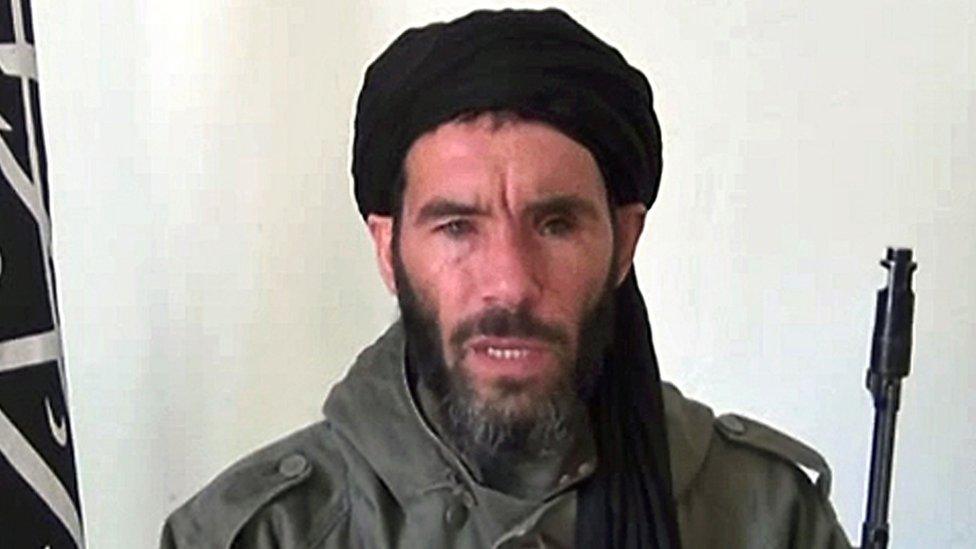

But both operations were mounted just weeks apart from each other, and by the same faction - that of the wanted jihadi commander, Mokhtar Belmokhtar.

The assailants have shown how easy it remains to drive around West African capital cities armed to the teeth and ready to commit mass murder.

This will raise fears that after Bamako and Ouagadougou, other regional capitals may be on the extremists' list of potential targets.

Three years after the French led a military campaign to put an end to jihadi rule in northern Mali's main towns, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) - and other Islamist groups - do not control any more swathes of territory.

Instead, Algerian-born jihadi commander, Belmokhtar, and his battalion known as al-Murabitoun are showing worrying capacities to recruit locally in order to strike throughout the region's main cities.

Moreover, the very young age of these new West African Islamist "martyrs" persuaded to carry out suicide missions is striking.

Alassane Baguian said that being scared would allow the militants to win.

Those who killed scores of hotel guests and staff at the Radisson Blu in Bamako were barely out of their teens.

So were the three militants who pulled the deadly trigger in Ouagadougou at the Cappuccino cafe and the Splendid Hotel.

There is no doubt AQIM is benefiting from most West African governments' inability to give hope to the younger generation.

Migration to Europe has long been seen as a way out of poverty for young and disillusioned souls.

Extremist groups may now offer a new generation of mostly uneducated youngsters a more attractive option.

Of all West African main cities, Bamako was considered the most vulnerable to the well-known presence of Islamist fighters on Mali's soil.

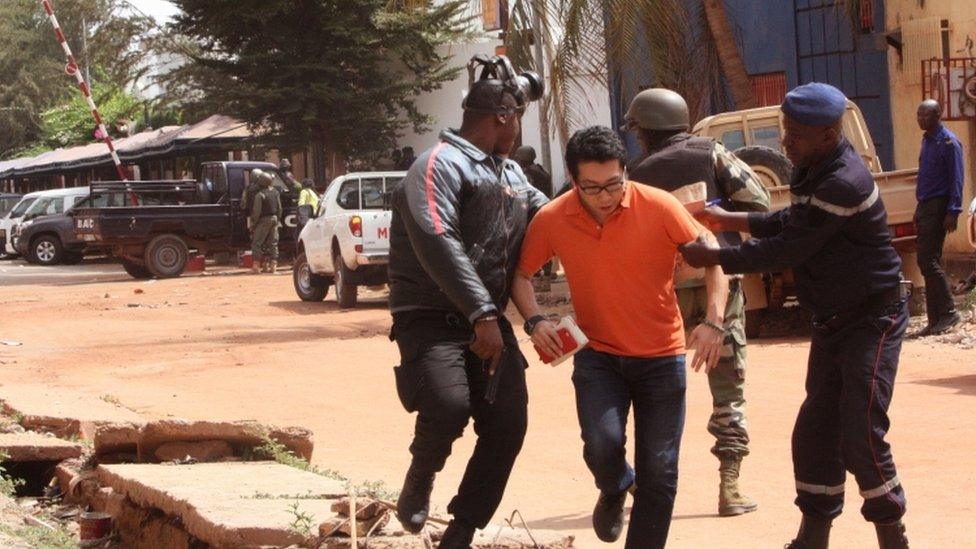

The siege on the Radisson Blu hotel in Mali's capital left 20 people dead

The attacks in Burkina Faso and Mali are both linked to a faction headed by Mokhtar Belmokhtar

Ouagadougou, though, did not have to worry much until Burkina Faso's former president Blaise Compaore was ousted following a popular uprising in 2014.

Mr Compaore had his nose in many conflicts throughout West Africa during his long years in power.

From Liberia to Ivory Coast and Mali, he had been in direct or indirect contact with many armed groups and rebellions.

Some rebel leaders even found a home in Ouagadougou, where peace deals have often been negotiated.

Mr Compaore's regime had somehow forged a relationship of good understanding with some Islamist groups such as AQIM.

The president's men were key for Western countries to secure the release of some of their kidnapped nationals, in return for ransoms.

But with the demise of the Compaore political machine, Islamist militants have lost that channel in Burkina Faso and the country is now vulnerable to their presence in the Sahel.

Observers also note that AQIM may be keen to show its strength at the time when al-Qaeda's rival, so-called Islamic State, is accumulating alliances around the world.

In the Sahel, Boko Haram pledged allegiance to IS last year.

This rivalry may also explain AQIM's renewed propaganda campaign. The group even issued live statements commenting on every step of the attack in Ouagadougou.

Finally, recent kidnappings of a Swiss national in northern Mali and of an Australian couple on the Burkina Faso's side of the border bear the signs of AQIM's methods too.

Kidnaps for ransom have been a major source of revenue over the years for the Islamist militants.

It was AQIM's first attack in Burkina Faso

But if the jihadis make it clear that Westerners are their prime targets, they also show their intention to strike throughout the whole region.

Radical imams were arrested in Senegal in recent months, suspected of having links to Islamist cells.

Wanting to prevent potential attacks, the Senegalese authorities imposed restrictions on the use of fireworks and gatherings during the festival period at the end of last year.

For each attack, the terrifying stories of those who survived massacres feed a growing climate of fear while West African governments struggle to provide a solid response.

But in the meantime, these survivors' dramatic tales have become all too familiar in the region.

Everywhere, populations are left with the dreadful question: when and where is next?

- Published16 January 2016

- Published17 January 2016

- Published18 January 2016