Jacob Zuma fights for his reputation

- Published

South Africa's President Jacob Zuma is experiencing the dark night of the political soul.

Last week he faced the embarrassment of being heckled in parliament during a chaotic session when he had to wait about an hour before he could make his state of the union address - an occasion that has all the pomp and ceremony as that of the US Congress.

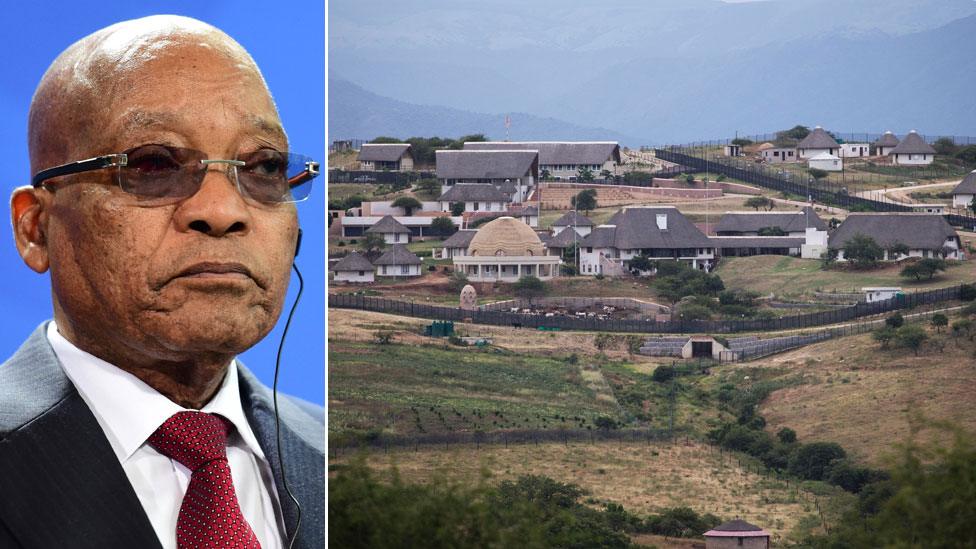

That came hot on the heels of the biggest political U-turn in democratic South Africa's political history when he agreed to pay back to the state some of the millions spent on upgrading his private home, Nkandla.

Yet it was a tactic that failed to pay dividends as the opposition went ahead with their case at the Constitutional Court in the hope that its ruling may open the way for impeachment proceedings against him.

And then there have been the other upsets in recent months.

Mr Zuma used some $23m (£15m) of state money to upgrade his Nkandla home

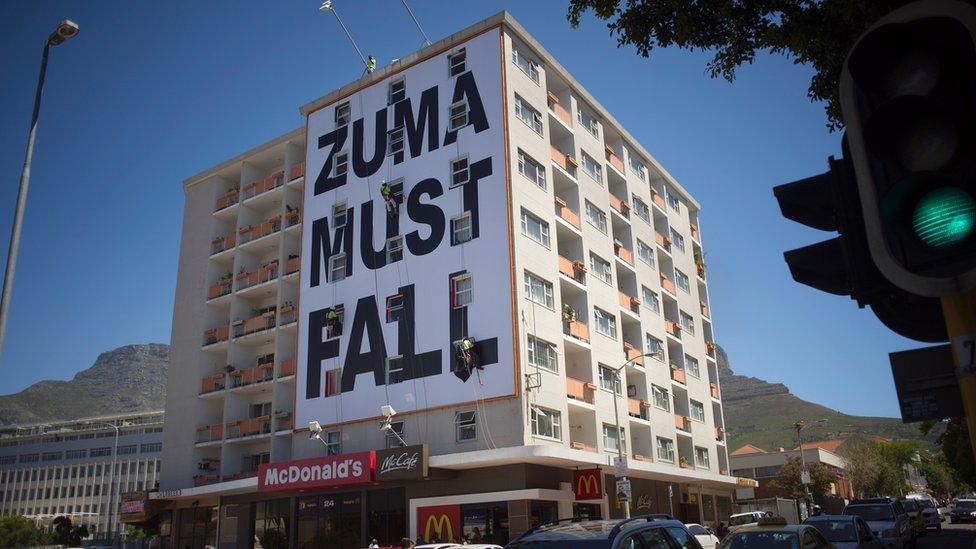

The finance ministers fiasco when he had three within two days, sending the markets into freefall and sparking the Zuma Must Fall demonstrations, which were rooted in the student protests that rocked the country last year.

And he was roundly mocked and forced to issue an apology for declaring at a business meeting that Africa was the biggest continent - forgetting the huge land mass that is Asia.

But Mr Zuma has always been able to laugh off the many controversies he has faced, including - before his election in 2009 - fighting off allegations of rape and corruption in relation to an arms deal.

And he has always relied on the backing of the governing African National Congress (ANC) to survive his scrapes.

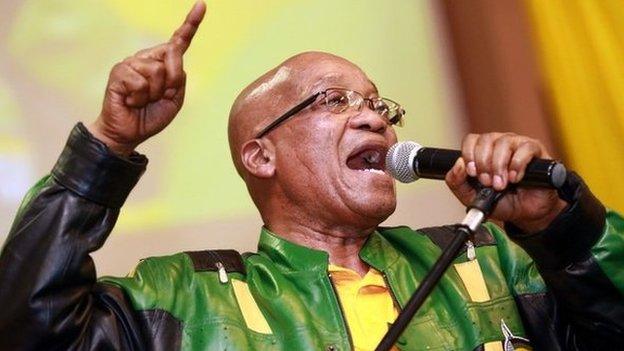

The president has come in for increasing criticism

So despite his recent political battering, Mr Zuma - an avid chess player - is unlikely to throw in the towel himself.

But the ruling of the Constitutional Court, which could take several months, and the outcome of upcoming local elections may ultimately decide his fate.

The president can only be removed by the ANC. The party has a parliamentary majority and so his own MPs would have to vote for him to be fired.

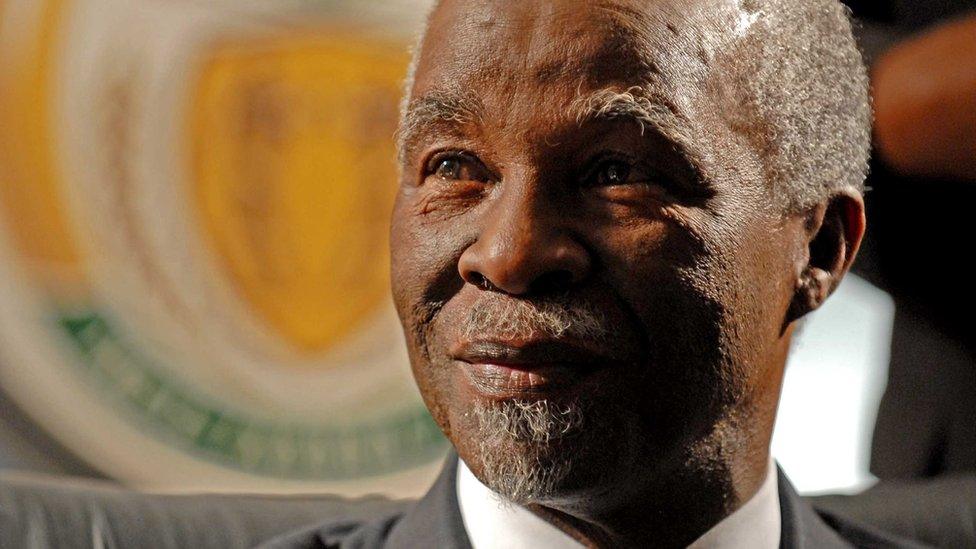

The other scenario is that the party's national executive could demand he go - as they did to Thabo Mbeki in 2008, external. There is no provision in the constitution for a president to be removed from power by recall but Mr Mbeki was forced to resign.

Former President Thabo Mbeki resigned in 2008 after a high court judge suggested he may have interfered in a corruption case against his rival, Mr Zuma

For the moment that is unlikely as senior leaders in the former liberation movement are currently at loggerheads with trade unions.

"Zuma will continue to take advantage of these divisions. There's no one strong lobby group about who will succeed him," Judith February, political analyst at the Institute for Security Studies, told me.

But she said there is a chink in the 73-year-old president's armour.

"He is not weakened enough, unless the local government elections go hugely against the ANC, then they might want to revisit the idea of recalling him," Ms February said.

So the climb down over Nkandla may have robbed him of his moral authority - but it is not checkmate, yet.

- Published11 February 2016

- Published9 February 2016

- Published6 April 2018