Buhari's battle to clean up Nigeria's oil industry

- Published

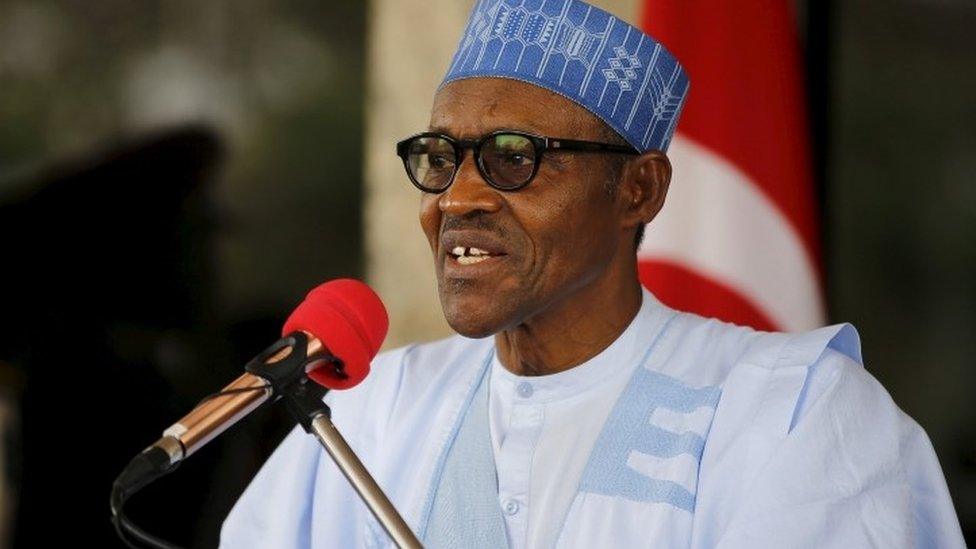

President Muhammadu Buhari has said he wants to deal with crime in the oil sector

The revelation by Nigeria's auditor general that $16bn (£11bn) of oil revenue went missing in 2014 has emphasised the scale of the task facing President Muhammadu Buhari in his efforts to clean up the oil sector. Neil Ford, an expert on oil, crime and security in Nigeria, outlines some of the ways in which huge amounts of money are stolen and assesses the president's chance of success.

The influence of oil on Nigeria is well known. From the soils of the Niger Delta to government revenues, it permeates the country's economy, politics and environment like nothing else.

It also encourages corruption and organised crime to such an extent that other African governments warn of the need to avoid becoming "another Nigeria".

There are many ways of illegally tapping oil revenues, and crime in the oil sector is easily the second biggest industry in the country after oil production.

President Muhammadu Buhari campaigned on a pledge to tackle corruption

President Buhari was elected last March on a platform to tackle this crime but similar promises by his predecessors have had virtually no impact.

The man, who some called Baba Go-Slow, has taken swift action on one of the biggest problems: Corruption and inefficiency within the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC).

Opaque oil company

The state oil company is involved in oil production but also regulates the sector and handles government oil revenues, creating conflicts of interest and opportunities for theft.

Last May, Mr Buhari chose Emmanuel Kachikwu as the man to sort it out. As former executive vice-chairman at ExxonMobil Africa, he is well aware of the Nigerian oil industry's shortcomings.

Now as NNPC group managing director and junior oil minister he has replaced the heads of all eight of the firm's divisions and said the corporation's monthly losses have been reduced to $15m (£11m).

Nigeria is Africa's largest oil producer but struggles to take advantage of the money earned from it

On 3 March, the government announced that it would break the NNPC up into different companies to be run on commercial lines whilst remaining state owned. However, the country's powerful trade union movement opposes the plans.

Ensuring good governance has become even more important as oil prices have tumbled and are now between $30-40 (£21-28) a barrel.

Nigerian oil exports were worth $78.3bn in 2014, followed by gas at $12.9bn. The next biggest exports were coffee, tea, cocoa and spices at just $1.2bn.

Oil theft

The theft of oil in the Niger Delta will be an even tougher nut to crack.

Oil theft - or bunkering as it is known in Nigeria - grew out of protests against the lack of benefit that people form the Delta were getting from oil production. They saw little investment and received few skilled jobs but experienced water, soil and land pollution.

Estimates vary, but bunkerers now take about 200,000 barrels of crude oil a day and even more production is kept out of use by attacks on pipelines and other infrastructure.

Some oil companies have blamed bunkering for pollution in the Niger Delta

As a president from the north, Mr Buhari will find calming the southern Delta region almost impossible in this divided country, particularly as some security and political officials have been accused of being involved in bunkering.

A more recent spin-off of bunkering has been piracy in the waters off Nigeria and neighbouring states.

Pirates have attacked tankers to either rob crew members or take the crude or fuel products for sale elsewhere in the region.

Subsidy fraud

Some of the least reported but most lucrative forms of crime in the oil industry revolve around fuel imports.

Although Nigeria is an important crude oil exporter, it imports most of its refined petroleum products and there are many ways to exploit the subsidies paid on these shipments.

One of the most popular is called round tripping, where fuel that has already been imported and a subsidy paid is taken just outside Nigerian territorial waters and back in again to double the subsidy.

The government has long paid subsidies on more fuel than Nigeria actually consumes.

Recovering stolen money

Mr Buhari's government is also seeking to recover as much oil money as possible that was spirited out of the country by corrupt officials and relatives of former rulers.

Top of the list are the billions of dollars reputed to be held by relatives of former military leader Sani Abacha but banking sector secrecy does not make its recovery easy.

Measuring success

The entire fuel distribution and refining sector will have to be rebuilt from the ground up, if Mr Buhari is to end the corruption and theft.

A good method of judging his success will be if the NNPC's four refineries are brought back into full use or replaced.

Nigeria's oil refineries have not been working properly for a long time so the country has to import fuel

Most fuel imports are only necessary because all four have been out of use or operated intermittently for many years, generating a lot of money for those behind the scams.

The enormity of the task makes it unlikely that the president will manage to tackle all forms of crime in the oil sector, even if he serves two four-year terms of office.

Given Nigeria's track record, he would do well to win the battle on even one front.

But his tough reputation on corruption means the chances of success are greater than they have been for many years.

- Published21 October 2015

- Published28 July 2023