Mobile drought insurance to protect Africa's farmers

- Published

A mobile insurance scheme to help small-scale farmers in Kenya ensure their agricultural produce against drought and other natural disasters is spreading to other parts of Africa, as Neil Ford explains.

A greater proportion of sub-Saharan Africans work in agriculture than anywhere else on the planet but only 6% of the population of Africa and the Middle East have any form of agricultural insurance.

"The insurance man" was a feature of many Western countries in past decades. Local agents collected tiny sums on a weekly basis to provide cover against long-term illness, funeral costs and unemployment.

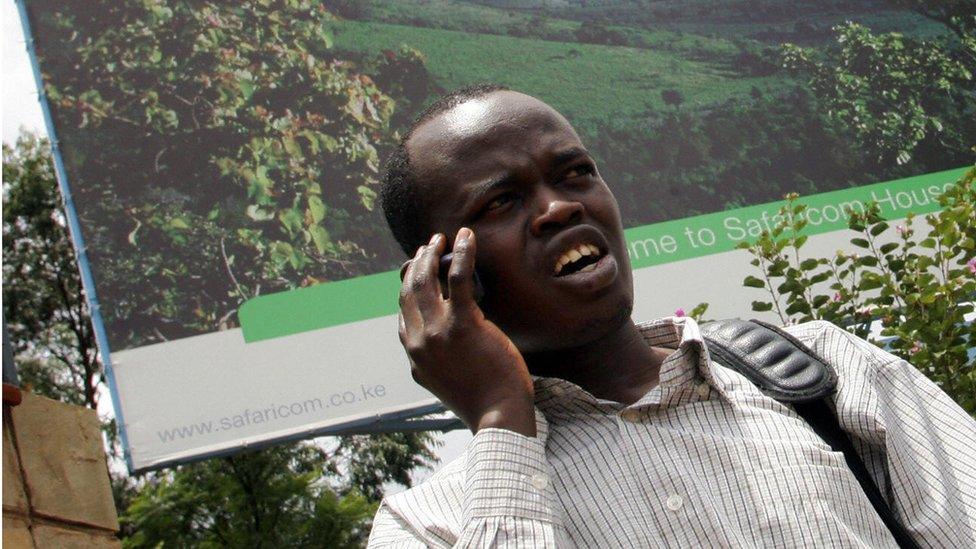

Kenya has now adopted this model for the 21st Century via mobile handsets.

Farmers with as little as one acre of land can insure themselves against extreme weather events.

They pay a 5% surcharge on purchases of fertilisers and seeds, which is registered with an insurance company, which in turn communicates with farmers via text message.

The first product was introduced on a small scale in Kenya in 2009 but has become increasingly popular. There are now no claim forms, as claims are automatically triggered by data from local weather stations and distributed in the form of mobile money.

This makes the system cheaper to operate and removes the possibility that farmers will make incorrect claims.

Kenya is seen as a leader in mobile financing in Africa

Safaricom is the market leader in Kenya at present but UAP Insurance is this year launching in Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda. Such insurance aims to help smallholders to even out the good and bad years.

It should also encourage farmers to invest more in their land, with some assurance that they will receive compensation if their crops fail because of poor weather.

There are others reasons for crop failure, including disease and insect infestation, but drought is the most common problem.

Kenya as a test bed

First, Kenya was the birthplace of the "pay as you go" telecoms model. By allowing users to pay for call time upfront, telecoms companies were able to get around difficulties in payment collection.

Most Africans have no formal bank account and residential postal services are limited.

Then, East Africa's biggest economy spawned mobile banking. M-Pesa was launched in 2007 and now has more than 20 million users in Kenya, out of a total population of 46 million.

More recently, the solar kiosk has come to the fore. Customers pay to charge mobile phones and other devices at small kiosks fitted with a couple of solar panels. In each case, the innovation has spread to other countries.

World Bank support

Kenya is now also taking mobile insurance on to the next level.

Majority of poor Kenyans are farmers

On 12 March, the Kenyan government and World Bank began to roll out the nationwide Kenya National Agricultural Insurance Program. This is a little more complicated as it uses a combination of mobile phones, crop yield data and statistical sampling.

It will also deploy GPS tracking for the first time, so cover can be provided for cattle in the north of Kenya, where drought is the biggest cause of death. Another big development is that the government will buy premiums for poor farmers from private companies.

Diarietou Gaye, the World Bank Country Director for Kenya, said: "The large majority of the poor in Kenya are farmers, so this programme has the potential to have a significant impact on Kenya's economic development.

"This programme aims at improving farmers' financial resilience to these shocks and will enable them to adopt improved production processes to help break the poverty cycle of low investment and low returns."

Ethiopian alternative

Mobile insurance is not the only innovative way of insuring farmers in Africa. Plans to insure 15 million Ethiopian smallholders were announced in early March.

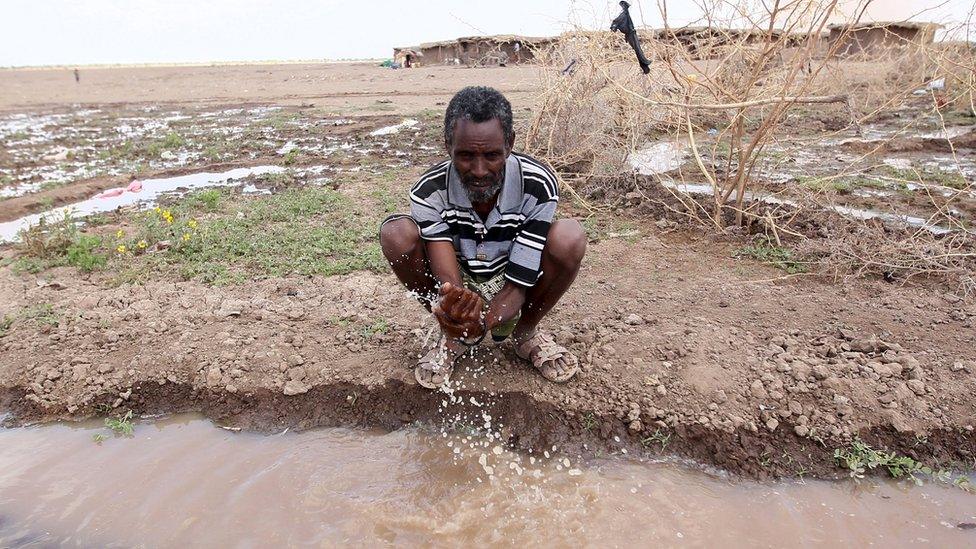

An El Nino-driven drought has affected many Ethiopian farmers

A group of Ethiopian, Dutch and international agencies will ask farmers to pay a 10% premium on the price of all agricultural inputs, including seeds, fertiliser and pesticide.

The average Ethiopian smallholder spends 2,500 to 3,000 birr ($115-140; £80-100) per season on inputs. They will then recoup the purchase price of these products from the Ethiopian Insurance Corporation if their crops fail because of weather.

The big difference, however, is that a vegetation index long employed by aid agencies will be used to define a drought situation.

In Ethiopia, using mobile phones was not an option because the government continues to control the telecoms sector and so the country has not benefitted from the private sector-driven mobile boom experienced by most other African states.

There are just 34 handsets for every 100 Ethiopians, leaving the vast majority of farmers without any means of modern communications.

Yet Ethiopia remains an outlier in this respect and many farmers in neighbouring countries do have access to mobile phones, so they are well placed to continue to benefit from the technological experiments undertaken in Kenya.

- Published6 January 2016

- Published5 June 2015

- Published27 November 2015