Libya: Can unity government restore stability?

- Published

Special security forces protect Libya's unity government

Last week, Libya's UN-backed Presidency Council sailed to the capital Tripoli and set up shop in the navy base.

They travelled by boat from Tunisia because their rivals in the capital closed the airspace when they tried to fly in. The doomsday scenario of rival militia clashes in Tripoli did not happen.

So is this just a honeymoon period, or is Libya turning a new page?

The numerous militias in western Libya who led the battle for the capital in 2014, forcing the elected parliament to move to the east, remain in place. They are now supporting the Presidency Council.

For five years, Libyan militias have been like an abusive partner in a relationship. The governments that have come and gone have persistently thought they can change them, but the end result is always the same.

The international community has been like an observant and nosey neighbour who has witnessed the abuse, and done nothing.

At each other's throats

A European ambassador recently admitted to me that outside powers are aware of the risks of forcing through this agreement without a clear consensus on the ground.

But they have run out of other ideas. "What do we do?" he asked.

To start with, it would help if world powers had a coherent strategy for good governance and nation-building.

They have talked only of fighting illegal migration and halting expansion of the so-called Islamic State (IS) militant group.

But these issues will not be resolved if Libya's military actors are at each other's throats.

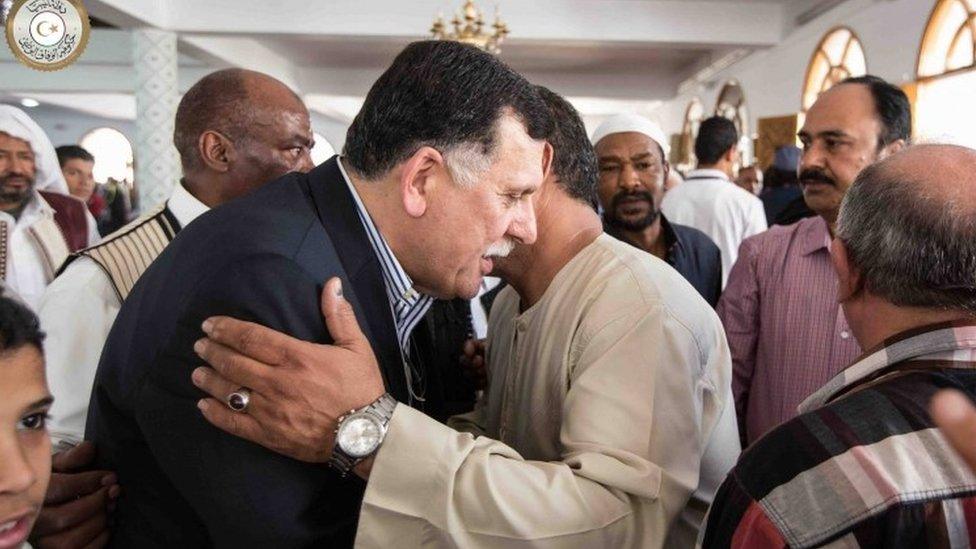

The new Prime Minister, Fayez Sarraj, has the unenviable task of broadening the UN-backed political deal and demonstrating that he will not be beholden to the militias supporting him.

Who is Fayez Sarraj?

Prime Minister Fayez Sarraj was born in Tripoli in 1960 into a prominent local family. His politician father, Mustafa, held office under King Idris, whose 18-year monarchy ended in 1969 when he was overthrown by Muammar Gaddafi

Al-Jazeera TV has described Mustafa Sarraj as "one of the founders of the modern state of Libya after its independence from Italy"

During the Gaddafi era, Fayez Sarraj was not prominent politically but did hold several posts at the housing ministry

After the uprising in 2011, he became a member of the National Dialogue Commission - a group trying to establish national consensus and unity in Libya

He was later nominated for membership of the House of Representatives for the constituency of al-Andalus in Tripoli

His choice as prime minister was seen as a compromise as he is not affiliated to any political party involved in the power struggle

On the sidelines of a Libya experts' forum in Tunis last week, I ran into many familiar people - there was the academic who refused to speak on the record because "I can get killed or kidnapped when I go back to Tripoli" and the former ministers who have gone into exile because of militia threats.

Salah el-Marghani, a former minister of justice, says Libyans have no choice but to be hopeful. But he is familiar with the challenges.

"We have to do away with the concept of revolutionaries, or militias, because those groups are uncontrollable - even if they support the government now.

"The moment they see the government contradicting their interests, they will turn against it."

He also thinks Western countries need to play a bigger, more effective role in disarmament because the government cannot deal with it on its own.

Legal limbo

However, the immediate priority for Europe and the US is finding potential partners in the fight against IS. This policy will entrench militia rule if it is not coupled with a disarmament and army re-integration plan.

Former Foreign Minister Mohamed Abdelaziz says foreign partners should put more effort into capacity building across various sectors rather than focus on military training alone.

It is also unclear how the contested UN-brokered political agreement will be implemented.

Parliament still has not voted for the cabinet that the council proposed. It must also vote on amending the constitutional declaration for the new government to assume its powers.

Until that happens, the unity government is in legal limbo.

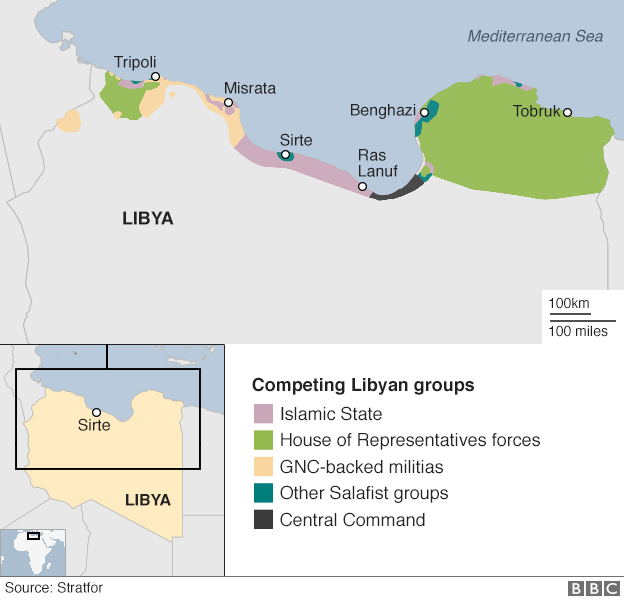

Under the UN-brokered agreement, the elected parliament, the House of Representatives, that sits in eastern Libya remains the nation's legislative body.

The former parliament, the General National Congress (GNC), that resurrected itself in the capital in 2014 becomes a State Council with an advisory role and veto powers.

Both these entities are now split right down the middle over the new government.

Adding to the confusion, the UN's Libya envoy, Martin Kobler, recently tweeted, external that the unity government "needs legitimacy to work" and that parliament must vote on it.

But he added, "if they can't decide" the government "has to go on".

Unless the plan is to do away with parliament in Libya and rewrite the political agreement, this issue cannot be bypassed.

The international community tends to look at Libya through a political lens focused on western Libya - a policy that has the effect of exacerbating tensions with the east. This area saw the bloodiest conflict with extremist groups for over a year.

Military actors there accuse rivals in western Libya of providing weapons to these groups.

With each side feeling like the rightful army of the country, the next battle will be how to unite these competing factions.

Libya has suffered from a lack of planning, both locally and internationally, that has hindered long-term stability. And politicians who bend to the will of the gun are not doing the country any favours.

Warlords have not been held accountable. Justice and reconciliation is an uphill struggle.

The question has always been how to achieve peace and unity. The answer remains as elusive as ever.