Djibouti’s thin-skinned democracy

- Published

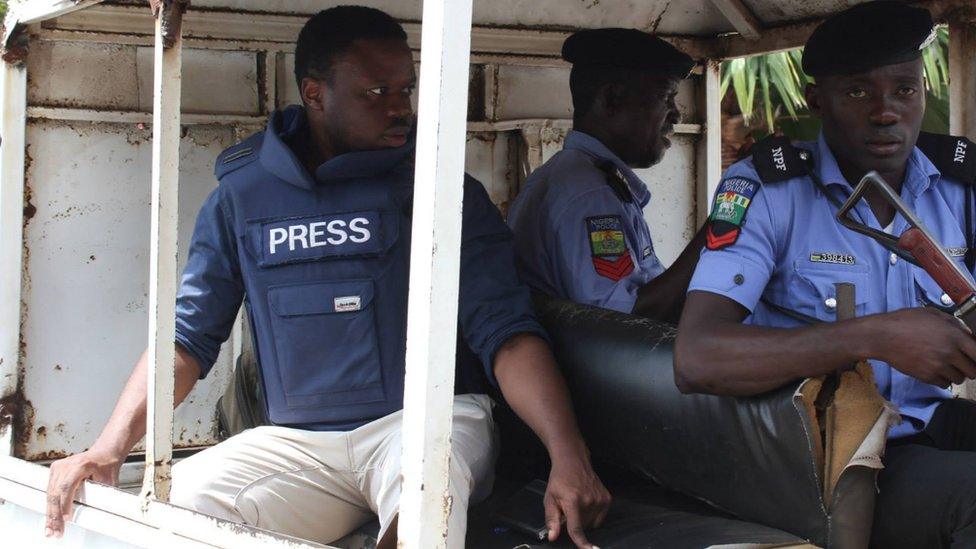

The BBC team was in Djibouti to report ahead of the presidential elections, due on 8 April

Djibouti is clearly a little nervous about democracy, as within 48 hours of arriving to report on the forthcoming elections, I was among a three-man BBC team detained and expelled without explanation.

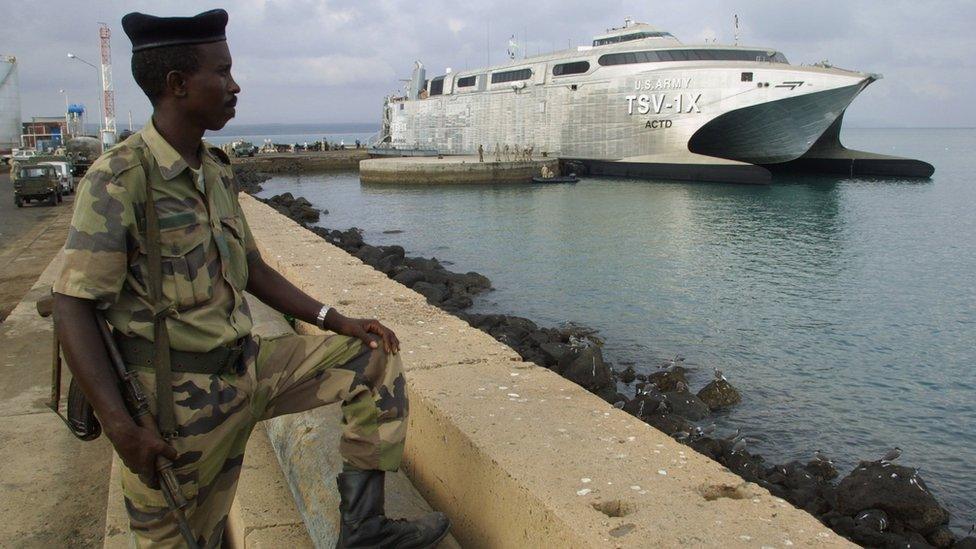

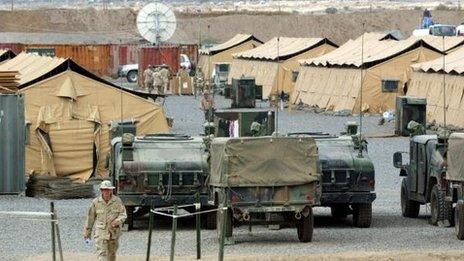

The Red Sea nation is an important security hub, hosting military bases from the US and France.

It was my first visit and I was most looking forward to seeing how the country operated with so many military personnel representing different interests.

As well as focusing on the election and its attraction to the world's military powers, we wanted to see how its economy was developing.

The heavy military presence is a win-win situation, Foreign Minister Mahamoud Ali Youssouf told me a few hours after our arrival.

Djibouti, which borders Somalia, Ethiopia and Eritrea, gains revenue and expertise from some of the best military forces the world had to offer as well as also enjoying good security, he said.

Tomi Oladipo has been a BBC journalist for nearly a decade

Later that evening, we went out for dinner to have a feel of Djiboutian life and a taste of the election fever.

Equipment seized

Our team included a cameraman and producer, and as we weaved through several narrow streets, at one point a group of children ran past chanting: "I-O-G! I-O-G!"

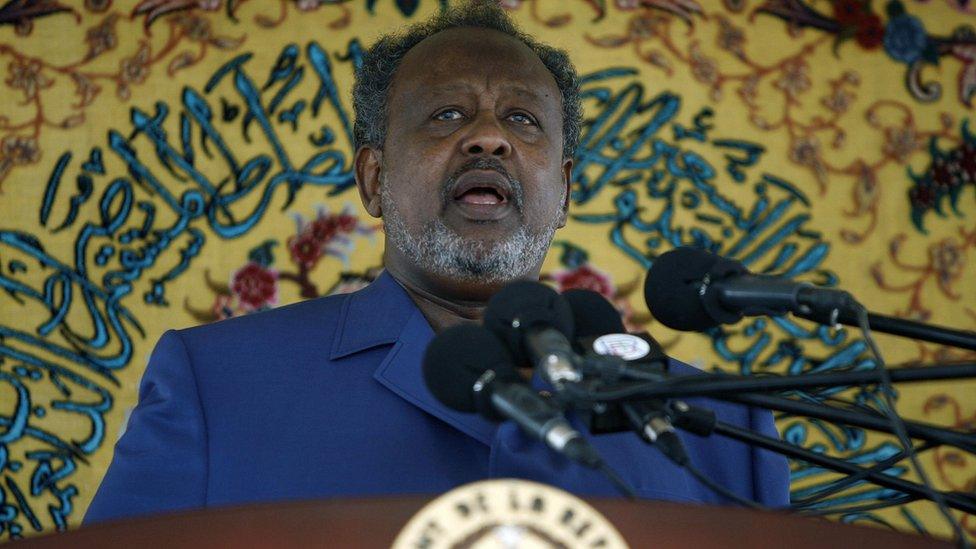

We had seen these initials, referring to President Ismail Omar Guelleh, on buildings and vehicles everywhere - and on a brief drive out of the capital city the next day we noticed that they had even been painted in white on the hills in the distance.

It was a strong reminder of the dominance of the man who has led Djibouti for 16 years - and looks likely to defeat any opposition challenge in this week's elections.

President Ismael Omar Guelleh has close security ties with the West

Omar Elmi Khaireh is one of two candidates actually running against the president, with three of the country's seven opposition parties choosing to boycott the poll entirely.

Mr Khaireh is no stranger to confronting authority, having got into trouble with French colonialists during the struggle for Djibouti's independence.

'Threat to the president'

On the day after our arrival, we interviewed him just before he set out for a rally.

With a yellow sash draped around his neck, he complained that the government was not providing a good atmosphere for opposition parties to operate.

Djibouti is not generally considered a safe haven for dissent.

It ranked 170 out of 180 on last year's World Press Freedom Index by the media watchdog Reporters Without Borders, with reports that legal and illegal means have been used to stifle journalists.

So we were not surprised to see the silver Suzuki car trailing us as we moved around the city, or the man secretly filming us on his mobile phone when we stopped outside a shop.

But we didn't anticipate what happened next: A group of at least six men approached us in a tranquil cafe where we were having lunch.

They flashed green ID cards and said they were from "national security".

Their leader, a tall man, possibly in his mid-thirties, announced they were taking us back to our hotel to get our equipment.

Our hotel was just across the street, but bizarrely, they tried to force us into a minivan with blacked out windows to get there.

Djibouti hosts a large army base for former colonial power France

We refused and eventually they agreed to walk with us, having confiscated our mobile phones.

The receptionist at our hotel tried to stick up for us, protesting at the aggressive behaviour of the men as they crowded the entrance to the hotel, demanding we hand over our cameras.

But his attempts only brought trouble on himself, and soon two men with "Police" spelled out in bold on the back of their polo shirts descended on him and bundled him into another vehicle.

They drove our team away in the first minivan, forcing us to put our heads down unless we wanted to be blindfolded.

No outside contact allowed

We headed east from our hotel, stopping at a building where we were held for most of the next 19 hours.

We met a man who hesitantly identified himself as Abdi. He appeared to be the person in charge and said this was a matter of national security. He offered us coffee and water.

We were interrogated for about eight hours in total, sometimes as a group, but mostly individually.

Why were we interviewing an opposition candidate?

Why had we chosen this specific time to be in Djibouti?

At times, their questions made me wonder if we had got the election dates wrong.

They also accused us of posing a threat to the president and of being sponsored by the opposition.

Djibouti hosts the largest US military base in Africa

They scanned and photocopied our passports.

It was almost laughable how they could not even decide what they wanted to charge us with.

Eventually Abdi, the man in charge, said the decision had been made from higher up to expel us from the country.

At this point in our detention, we had still not been allowed to communicate with anyone in the outside world.

The people holding us left for the day and handed us over to another bunch.

These ones were younger, mostly in their twenties and appeared less willing to reason with us, preferring to focus on chewing mouthfuls of khat, the plant traditionally used as a stimulant in the region.

Djibouti's port is a gateway to the Suez Canal, one of the world's busiest shipping routes

At one point they told us it was time to leave. They took us to the airport but they could not get us on the 23:30 GMT Kenya Airways flight, so we were taken back to the national security building.

This time we were shown a room, which I suppose was for security guards. In it there were mattresses on the floor for us.

As the three of us lay there, we thought and talked about our loved ones and colleagues who would be trying to reach us.

We barely slept until daylight. Later in the morning we were taken to the airport again.

We rushed to the plane, which had been delayed for us.

This time we had our mobile phones in hand and were able to announce that we were safe.

- Published16 June 2015

- Published18 April 2023