Dismissal of case against Kenya's Ruto huge blow to ICC

- Published

The ICC said there was insufficient evidence against Joshua arup Sang (l) and William Ruto (2nd from right), pictured here shortly after the court's finding was announced

The decision by the International Criminal Court (ICC) to "terminate" charges against Kenya's Deputy President William Ruto and a co-accused radio journalist effectively brings to an end the international efforts to pursue justice for the victims of violence that followed the country's disputed elections in 2007.

More than a thousand people died and half a million were forced to flee their homes during inter-ethnic clashes driven by fierce political rivalries and the pursuit of power.

The ICC's decision - a majority decision made by two of the three judges - will come as a blow to the victims of the violence and their families, who want to know the truth behind what happened, who was responsible - and to claim compensation.

"This ruling does not mean the violence didn't occur, it does not mean that the victims do not exist," said Nelly Warega, a human rights lawyer who represents some of the victims.

"We have been looking up to the ICC and hoping that the victims were going to acquire justice after what they went through. This is a huge disappointment for us."

But she still had hope that the case, which is going through the Kenyan courts, could still bring justice, even though it looks like "that light is dwindling and looks very dim right now."

"What we are working towards is compensation for them," added Ms Warega, who is with the Kenyan branch of the International Commission of Jurists.

'Insufficient evidence'

The pain and the tribal rifts are still felt, as nobody has yet been held accountable for fomenting the violence which was widely seen as having been organised rather than spontaneous.

The ICC is known as "the court of last resort" and in 2011, after investigating the post-election violence, its then prosecutor Luis Moreno Ocampo indicted six people on charges of crimes against humanity for their alleged role in the violence - among them the men that shortly afterwards went on to become president and deputy president.

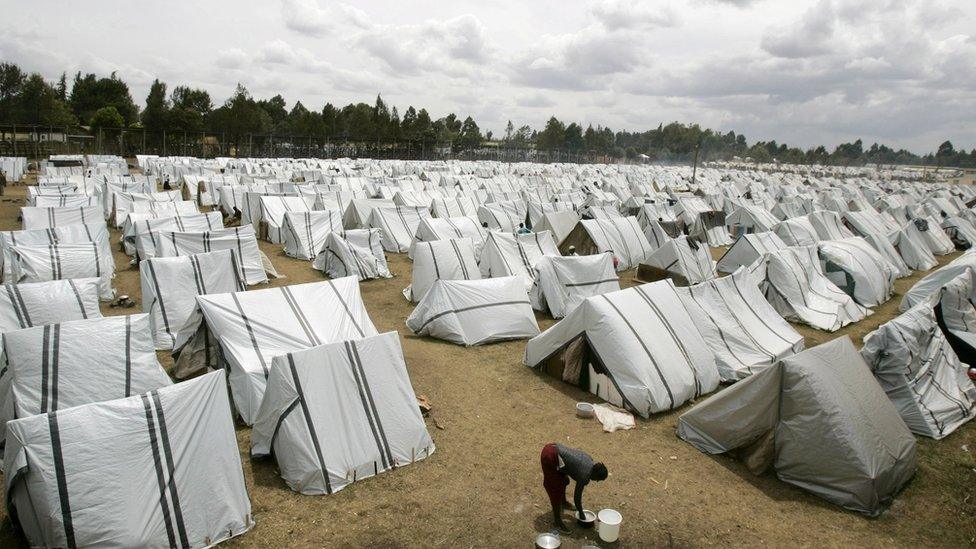

The four months of violence following the 2007 elections left about 1,200 people dead

Mr Ruto appeared in court first - in 2013. President Uhuru Kenyatta became the first standing head of state to appear at the ICC in the Hague in 2014, but charges against him and three others were dropped later that same year.

The prosecution said witnesses had been bribed and intimidated, and the Kenyan government refused to hand over documents that could have been used in evidence.

Two cases remained - that of Mr Ruto and his co-accused, Kenyan radio executive Joshua arap Sang.

The prosecution claimed it faced a similar challenge over witness interference, but in February the court denied its request to allow the use of evidence which had been collected by witnesses before they changed or withdrew their testimony.

On Tuesday, two of the three ICC judges agreed with Mr Ruto's lawyers that there was not enough evidence for the case to continue.

"On the basis of the evidence and arguments submitted to the chamber, Presiding Judge Chile Eboe-Osuji and Judge Robert Fremr, as the majority, agreed that the charges are to be vacated and the accused are to be discharged," a statement from the ICC said.

Judge Fremr said there was simply not "sufficient evidence on which a reasonable trial chamber could convict the accused".

Lawyer Wilfred Nderitu said the ruling would come as a disappointment for victims

The presiding judge declared it should be classed as a mistrial because "the weaknesses in the prosecution case might be explained by the... tainting of the trial process by way of witness interference and political meddling that was reasonably likely to intimidate witnesses".

Judge Herrera Carbuccia disagreed, believing there was still a case to answer.

In 2013, Kenyan journalist Walter Barasa was charged with "attempting to corruptly influence a prosecution witness", after the new chief prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, alleged he was part of a network of people close to the Kenyan presidency that was trying to undermine the investigation. Two people have been indicted for influencing witnesses.

The prosecution is allowed to appeal against Tuesday's ruling, and it will not prevent a new prosecution in the future if more evidence emerges.

Court 'powerless'

Kenyan High Court advocate Saitabao Ole Kanchory said the process was "bungled" by the ICC, which did not do its own investigation, instead depending on evidence gathered by a third party.

"I think the ICC will have to do some soul searching and the Kenya case has exposed the underbelly of the court," he said.

"It is supposed to be this all powerful court set up by the powers of the world, but it has shown it is powerless.

"If there was a case of witnesses being intimidated they should take the necessary steps against those people - the court has the power to do that."

Uhuru Kenyatta (L) and William Ruto were running mates in the 2013 elections

It is a huge blow to the ICC, which has been criticised for focusing most of its attention on Africa.

It also shows the difficulties of attempting to build a case against a sitting president or deputy president.

Mr Kenyatta and Mr Ruto were on different sides in the lead up to the 2007 elections.

Mr Kenyatta, an ethnic Kikuyu, was supporting incumbent President Mwai Kibaki, while Mr Ruto, a Kalenjin, was backing opposition leader Raila Odinga, who is from the Luo community.

It is not known who actually won the election, but the Kenyan electoral commission backed Mr Kibaki's claims of victory, and the violence followed his hasty inauguration.

Those in Kikuyu regions were targeted first.

Dozens of people - mostly women and children - were locked inside a church and burned alive on New Year's Day.

More than half a million people were forced from their homes during the post-election violence

Retaliation led to a downward spiral of violence as people from the different ethnicities turned on each other.

Mr Kenyatta was accused in a report by the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (KNCHR) of attending meetings in early 2008 to plan for retaliatory violence by his Kikuyu community.

Mr Ruto faced three separate charges of crimes against humanity, as the ICC accused him of being a "principal planner and organiser of crimes" against supporters of Mr Kibaki.

Two months after the violence began, former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan's mediation efforts led to a power-sharing agreement between Mr Kibaki and Mr Odinga, and they formed a coalition government.

'Long overdue'

Once bitter rivals but united against the ICC charges, Mr Kenyatta and Mr Ruto campaigned together in the last election to form the Jubilee Coalition, which is still in power.

President Kenyatta issued a statement welcoming the ruling.

Supporters of William Ruto cheered the ICC's decision

"This moment is long overdue but no less joyful. I join my brothers in celebrating their moment of justice," he said.

"The victory in this matter is partial and the quest for justice incomplete, because the International Criminal Court elected to blindly pursue ill-conceived, defective agenda at the expense of accountability," he added.

The dropping of charges against Mr Ruto levels the political playing field, but it is hard to predict what impact that will have on the complex Kenyan political arena in the lead up to the next election.

- Published12 February 2016

- Published13 September 2022

- Published6 January 2015

- Published6 October 2014

- Published10 September 2013