Barbie challenges the 'white saviour complex'

- Published

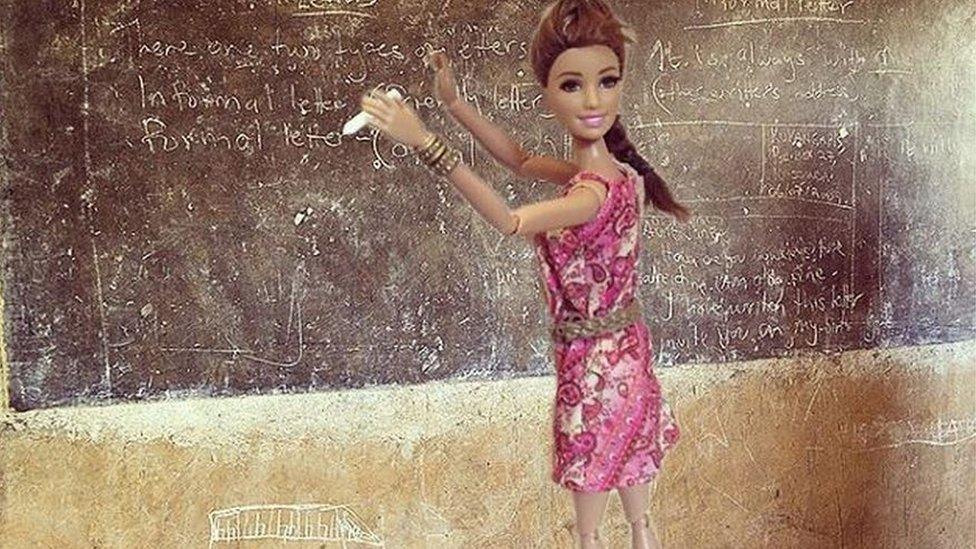

"Who needs a formal education to teach in Africa? Not me! All I need is some chalk and a dose of optimism."

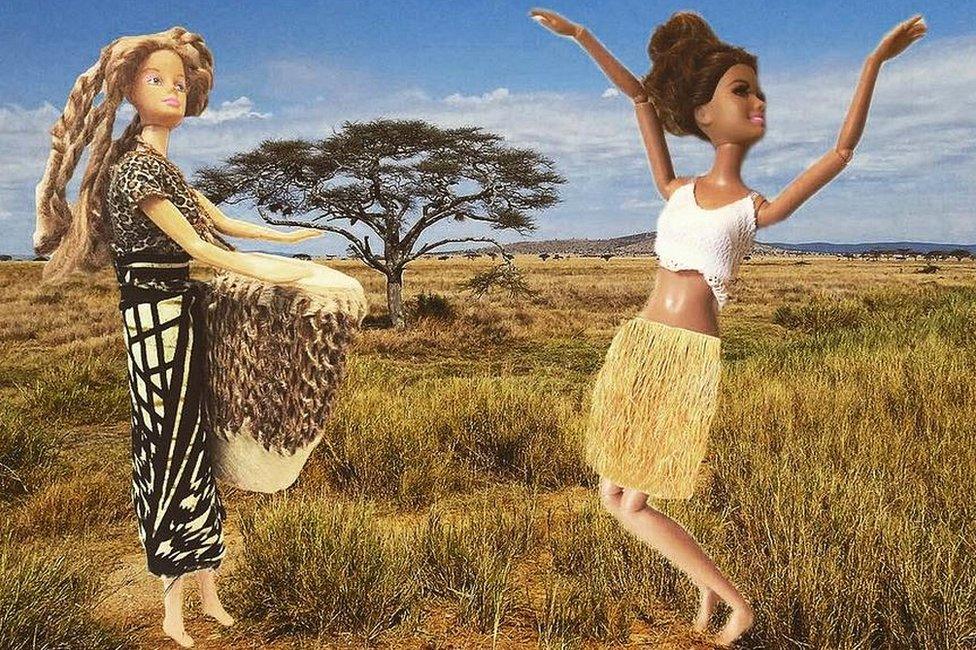

Barbie has ditched her riding gear, her ball gown and her ballerina costume and travelled to Africa to help the people there, while still managing to stay fashionable.

That is at least according to a much talked about Instagram account, Barbie Savior, external, which is charting her imaginary volunteer journey.

It starts with her saying farewell to her home in the US and wondering if the "sweet sweet orphans in the country of Africa" are going to love her the way she already loves them.

The satirical account encapsulates what some see as the white saviour complex, a modern version of Rudyard Kipling's White Man's Burden.

The 19th Century Kipling poem instructed colonialists to "Fill full the mouth of Famine And bid the sickness cease". Today, Barbie Savior says she is going to love the orphans "who lack such an amazing Instagram community".

Because of the history of slavery and colonialism, many people in Africa find such attitudes deeply patronising and offensive. Some argue that aid can be counter-productive, as it means African countries will continue to rely on outside help.

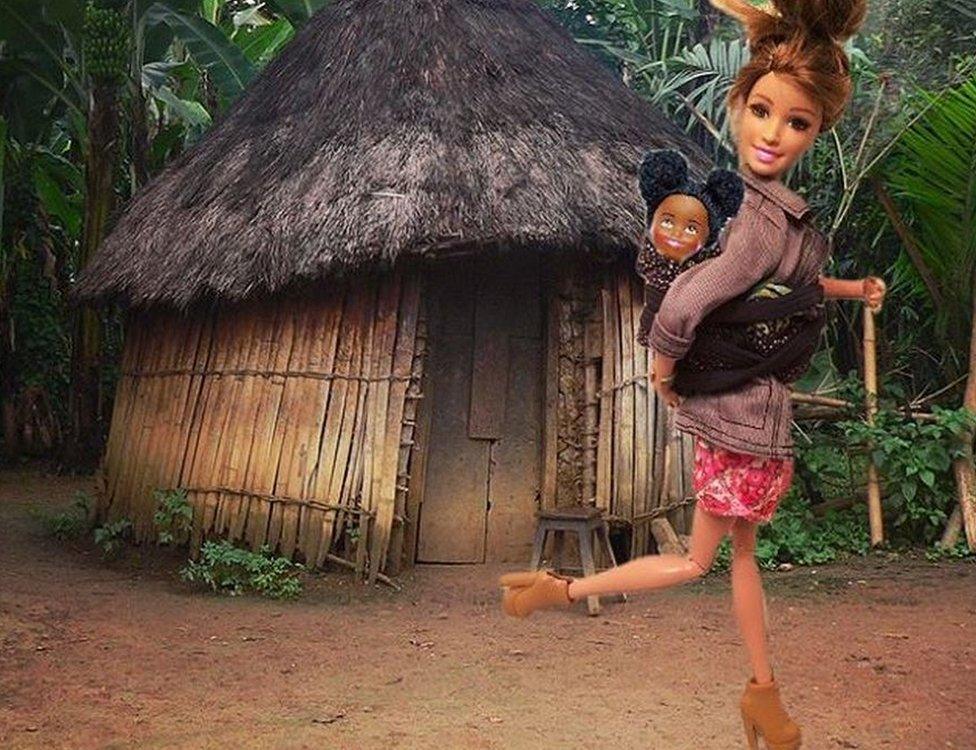

"At first, she was scared of my white skin... We are bound together by spirit and our humanity. And now, by cloth. I feel like mothering all of this country's children."

"Just taking a #slumfie amidst this dire poverty and need. Feeling so #blessed and #thankful that I have so much more than this"

US-based Nigerian author Teju Cole described the complex, external in a 2012 essay as a belief that "a nobody from America or Europe can go to Africa and become a godlike saviour, or at the very least, have his or her emotional needs satisfied".

The two American women behind Barbie Savior said that through their 10 years combined experience of volunteering, studying and working abroad they began to question what they once thought was right and good.

"From orphanage tourism, to blatant racism in [the] treatment of local residents, to trafficking children in the name of adoption - the list of errors never ends," the two - who have chosen to remain anonymous - wrote in an email to the BBC.

They are not against all aid work and when asked about medical staff going to help the fight against Ebola, replied:

"We have seen short-term medical teams do amazing things, as well as act in inexcusable ways."

They say that aid workers should act in the same way they would back home.

"For example, nurses in America are not allowed to take Instagram photos of their patients and post emotionally captivating blurbs about how tragic their life is."

They note that in the US, and other Western countries "it was decided that a person's privacy is more valuable than the need of the caretaker to have an emotional outlet" and the same standards should apply in Africa.

"As a Westerner coming into a developing country, whether to live or visit, you must be aware of the privilege your skin colour affords you," they argued.

And they want people to "stop treating 'third world countries' as a playground for us to learn and gain real life experience from".

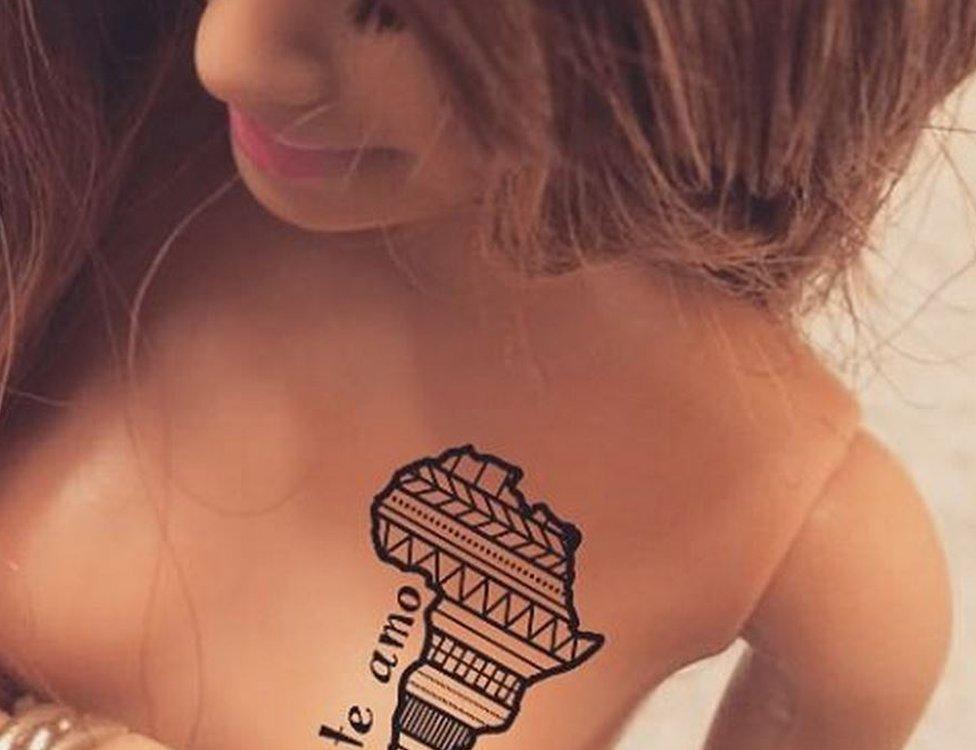

"Only hours after landing I knew that I needed no more time to make a permanent, life-long decision. One week later, I committed."

There are plenty of opportunities for Westerners to work abroad, from long-term placements with established NGOs to the growing market for the short-term "voluntourism" experience.

According to a 2008 estimate, external, 1.6 million volunteer tourists spent around $2bn globally.

On the GoAbroad.com, external site, which pulls together volunteering opportunities, there are more than 1,600 programmes in Africa alone.

One of the organisations featured is African Impact, external which says in its publicity that volunteering is not only about the "skills that volunteers bring, but also about what this magnificent continent, its warm people and amazing wildlife can give volunteers in return".

It sends volunteers to work in health, education and conservation projects across southern and east Africa, and in 2016 it is recruiting around 2,500 people.

African Impact managing director Greg Bows says that out of naivety some volunteers they get do come believing they can solve a country's problems - though one of its slogans encouraging people to sign up is "let's save Africa's wildlife".

But Mr Bows adds that he is now using some of the Barbie Savior pictures during the induction process to disabuse new volunteers of those ideas.

Barbie Savior's creators take particular issue with unqualified people doing jobs that they would never be allowed to do at home.

African Impact's publicity for a position helping at a school in Zambia, external, says "you do not have to be a qualified teacher to be a volunteer", but Mr Bows points out that none of his volunteers teach whole classes, rather they can provide vital one-to-one support.

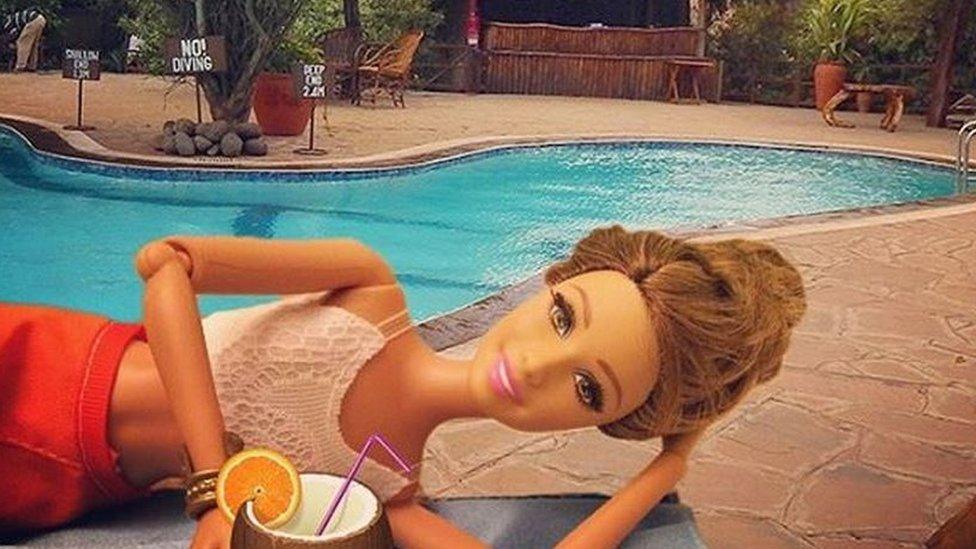

"Even amongst this devastation and poverty, amongst so much need... A girl's gotta relax from time to time!"

He says that local guidelines are observed and argues that in general, as long as the limitations are accepted, volunteering can make a difference.

He does acknowledge though that there are organisations that do not have the same standards as African Impact and that for him Barbie Savior highlights the need for regulation in the industry.

But for critics this goes beyond the sphere of volunteering, and Barbie Savior's creators say they are trying to tackle not just the attitudes but the damage that they can cause.

Kenyan writer and development consultant Ciku Kimeria, external says that "the development sector today is still chock-full of examples of benevolent and sometimes not-so-benevolent paternalistic attitudes from the West", and she draws a link with the colonial mindset.

She says that this can sometimes lead to people with an "average undergraduate education and a lack of development experience... getting to chair meetings of local experts with decades of experience".

"The people living in the country of Africa are some of the most beautiful humans I have ever laid eyes on. I feel so insignificant next to my new friend Promise."

She has come across some development workers who "are very uneasy with me and other Africans who don't fit into the mould of what they were told about African people.

"They do not know what to make of Africans who are better educated than them, more articulate than them, well-read, knowledgeable about the world and so on."

Ms Kimeria says aid work and volunteering can work as long as some basic points are observed.

Firstly, that people are aware that they are coming not to "save Africa" but to help out locals who are already doing the work.

Secondly, they need to acknowledge the privilege that they come with.

And thirdly, they need to know the real place they are visiting, not the place they imagined back home.

"Learning to dance like a native. May the movement of my hips be as intense as the belief I have in myself!"

Barbie Savior's creators are not intending to offer solutions themselves, but what they are happy about is that the Instagram account has sparked discussions and raised awareness about the white saviour complex.

But is Barbie Savior herself listening?

As she puts it: "I have noticed people informing me that Africa is a continent and not a country. I hope you can forgive my mistake. I have so much to learn.

"But I do know one thing for certain, and that is that my love for this place is bigger than any country! Even bigger than the country of Africa!"