South Africa's unemployment crisis: Begging for jobs

- Published

Young men holding placards market themselves as painters, plumbers, gardeners and builders in the busy streets of South Africa's main city of Johannesburg.

This is not an uncommon scene in a country where unemployment stands at 26.7% - the highest on record since 1995, a year after the end of apartheid.

Since the beginning of the year, 300,000 jobs have also been lost, with the hardest hit being young people.

"I've given up on job hunting after 12 years of trying, it's depressing," says Thabiso Molaka, who sells mobile phone chargers in Hyde Park, one of Johannesburg's posh northern suburbs.

"I decided to start selling goods to feed my family," says the 28-year-old, who finished high school and travels hundreds of kilometres to get to Johannesburg every day.

'Crisis'

Of South Africa's estimated five million people who are unemployed, 3.5 million are under 35, more than 170,000 of them, including Anthea Malwandle, are university graduates.

A photograph of Ms Malwandle holding a placard stating she had a degree in chemical engineering and was jobless recently went viral on social media.

"After job hunting for more than a year, I wondered if all the money and hard work spent on tertiary education were worth it," she subsequently told a local radio station, external.

Thanks to the publicity, Ms Malwandle's future seems secure after a number of prospective employers phoned in, offering her a job.

The South African government has come under fire from its political opponents who blame it for the country's economic woes.

Most of South Africa's unemployed are under the age of 35

One in four people in the labour force failed to find work in 2015, a far cry from the government's goal of reducing unemployment to below 15% by 2014.

The government insists it has made progress in tackling youth unemployment, though Buti Manamela, the minister in charge of youth development, admits there is a crisis.

He says the government has been the biggest employer.

"But this is unsustainable, the private sector has to come in," the minister says.

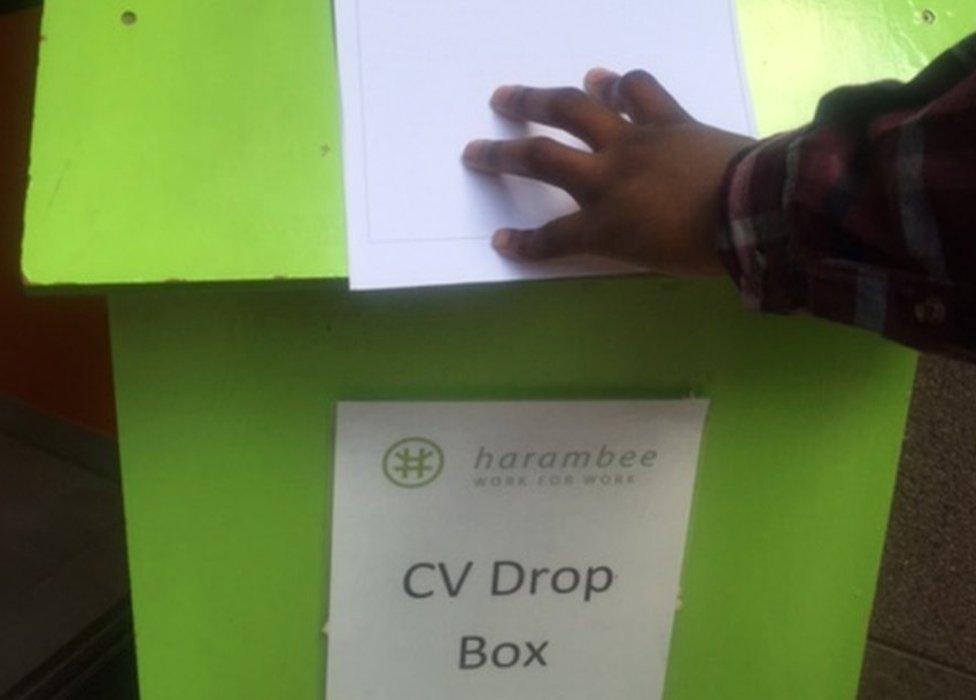

Most days in downtown Johannesburg, university students line up to drop off their CVs at a job-seekers centre called Harambee.

The organisation tries to link young people who are currently locked out of the formal economy with prospective employers.

They are taught about the dos and don'ts of how to handle themselves during job interviews - and tips such as having professional email addresses.

'Feeding graduates'

"In most cases, young people are not aware of job opportunities that exist, so we go out there to recruit them," says Lebo Nke, an Harambee executive.

Looking for a job takes up a lot of energy.

A job seeker's centre, Harambee gives graduates tips on finding employment

Harambee has also found that feeding job seekers makes things a little easy for them.

"Just by introducing peanut butter sandwiches and fruit, test assessment scores went up by 30%, because many of them come to our centres very hungry and therefore not able to put their best foot forward," says Ms Nke.

Ms Malwandle may have captured the heart of the nation with her innovative way of getting the attention of potential employers.

But the hundreds of thousands of graduates who remain unemployed cut face are unlikely to be so lucky.

- Published24 February 2016

- Published2 May 2014