Is South Africa’s public broadcaster using apartheid tactics?

- Published

There have been violent protests in the northern province of Limpopo

South Africa's public broadcaster has come under fire for its decision to ban the broadcast of footage showing the "destruction of property" during violent protests.

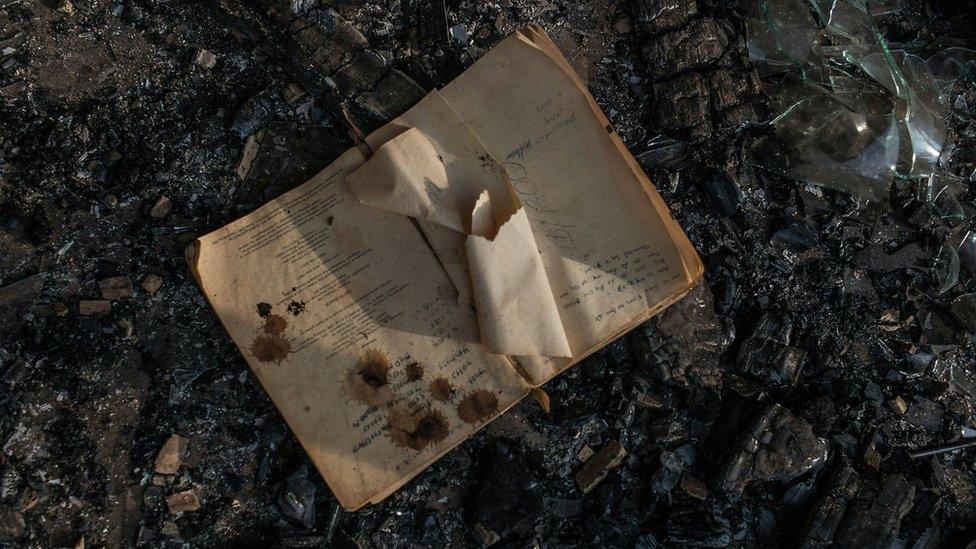

The announcement from the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) comes in the run-up to crucial local elections in August - and in the aftermath of violent protests in the northern province of Limpopo in which more than 20 schools were torched.

"As the SABC, we are very clear that we are going to cover protests that are happening and we are going to make sure that we are going to do that without fear or favour," its statement said.

"When we are covering those protests where there are people destroying the property, we are not going to show that footage on our television. If there is sound that will encourage that behaviour then we will not use that sound on our radio stations."

South Africa has a history of violent demonstrations, going back to the days when people protested against white minority rule under the violent apartheid system.

The school burnings over the past month were prompted by villagers angered that moves to include their neighbourhoods into a new municipality would delay efforts to get them better housing and water.

Teaching has not yet started again in areas where the schools were torched

The education ministry says hundreds of school children may miss their mid-year exams.

The government has provided more than 76 mobile classrooms but teaching has not yet resumed.

The SABC's ban has ignited wide condemnation from free-speech advocates, including the South African National Editor's Forum (Sanef).

"We would like to urge the SABC to review that decision because there is no evidence at the moment to prove that the broadcast of such incidents fuels them," Sanef chairman Mpumelelo Mkhabela said.

"Until such time that there is such research and concrete proof, I do not think such a drastic decision should be taken by the SABC."

'Puppet master'

Opposition parties, which regularly complain that the public broadcaster has turned into a state broadcaster, also weighed in.

Inkatha Freedom Party's parliamentary whip Liezl van der Merwe accused the SABC of flouting the Broadcasting Act.

She said the SABC, sometimes referred to by its critics as Fawlty Towers after the British sitcom because of its cash problems and boardroom battles, was required to "provide news and public affairs programming which meets the highest standards of journalism, as well as fair and unbiased coverage, impartiality, balance, and independence from government, commercial, and other interests".

South African parties are currently campaigning ahead of August's local elections

The main opposition Democratic Alliance was also scathing.

Phumzile Van Damme, the party's shadow communications minister, alleged the governing African National Congress (ANC), which has its quarters at Luthuli House in Johannesburg, was playing puppet master.

Hlaudi Motsoeneng, the corporation's chief operations officer, was hell bent on "fully turning the SABC into a propaganda portal for Luthuli House", she said.

Ms Van Damme called on the Independent Communications Authority of South Africa (ICASA) to urgently intervene as it had been tasked with ensuring the upcoming elections were covered fairly.

Even the trade union movement Cosatu, an ally of the ANC, pointed out that the fight against apartheid had also been against censorship.

"We are not a nanny state and therefore do not need an overprotective public broadcaster to take care of us," the two million-strong workers' federation said, external.

"What we have seen and learned is that once censorship starts, it never stops because those who are empowered to censor and impose blackouts, start to develop bottomless sensitivities and discover more activities that they feel should not be flighted on television."

'Attention-seeking anarchists'

Predictably Communication Minister Faith Muthambi, often accused of being lethargic, welcomed the ban, saying the decision was taken to foster social cohesion and was not about self-censorship.

SABC says it has a duty not to incite violence

"We unequivocally condemn the destruction of public and private infrastructure," she said.

"It is our belief that the decision by the public broadcaster not to show footage of people burning public institutions, such as schools and libraries, in any of its news bulletins, will go a long way to discourage attention-seeking anarchists."

However, some senior staffers at the SABC, who wanted to remain anonymous, told me that the decision goes against every fibre in their being as independent broadcasters.

When I asked Mr Motsoeneng whether there was dissent in the newsroom following his decision, he said the SABC was not about individuals.

"All employees must adhere to the editorial policy of the leadership of the SABC. We don't need permission from our employees. We have a duty not to incite violence through our cameras," he told me.

"If you don't want to work for the SABC you can go. There are many people out there looking for work."

So despite the criticism, the ban is to remain - though the bickering is likely to continue.

And South Africans have been left wondering whether apartheid tactics have been reincarnated in a democratic era, with the public broadcaster becoming a government mouthpiece.

- Published4 May 2016

- Published12 May 2016

- Published9 July 2024