Cult of Dos Santos and the state of Angola

- Published

Parts of the capital, Luanda, resemble Dubai

In many ways the Angolan capital, Luanda, feels like Africa's best kept secret. Fifteen years after emerging from a bitter civil war in which Cold War rivalries were counted in lives lost, parts of the city look like Dubai.

Smart glass-fronted buildings reach up to the sky and virtually every vehicle downtown is a large shimmering 4x4. This is what oil money looks like.

It has paid for Angola's impressive infrastructural development, five ports and an expansive road network, a welfare state that many other African nations could only dream of, with hospitals populated by top-class Cuban doctors and schools where the textbooks are free.

Yet when global oil prices plummeted, the cracks began to show. Angola found itself in fiscal crisis, unable to pay the bills, restock its hospitals, pay the doctors or collect the rubbish.

A yellow fever outbreak helped to expose the shortcomings of what some consider to have been skewed priorities and a sense of complacency in a country that imports most of what it needs and depends almost exclusively on oil.

The slump in prices appears to have encouraged Angola's leaders to open up to the rest of the world and expand ties beyond the established links with Cuba, Brazil, China and Portugal.

It is an "opportunity rather than a crisis", says Antonio da Silva, who heads APIX - the Agency for Investments and Exports Promotion - a body set up to encourage more foreign investment and trade.

He admits the time is long overdue for Angola to diversify and the oil shock could help to accelerate that long promised change and recalibrate Angola's relationship with the world.

He points to fast-food chains, agribusiness and environmental companies eager to do business here - but when I ask him about corruption, he plays it down.

Angola is the 12th most corrupt country in the world, external, according to Transparency International.

The rankings measure perceptions, but a poor rating does little for business confidence surely, especially with potential "suitors" such as Britain, which now has legislation targeting companies that pay overseas bribes.

New systems have been put in place for foreign businesses "cutting out the middle-man", Mr Da Silva offers by way of assurance.

But what if the middle-men and women are at the top, as many commentators would seem to suggest?

Mr Dos Santos has ruled the oil-rich nation for 37 years

At the helm of this African oil giant, is President Jose Eduardo dos Santos. A man who has led Angola for the past 37 years and made his country a beacon of hope for others held back by poor infrastructural development.

He has declared his intention to stand down from office after elections next year. Stepping down would seem to indicate a loosening of his grip on power and a change of direction, but the appointment of his daughter to a top job, suggests otherwise.

Isabel dos Santos, the richest woman in Africa, has just been named president of the state oil giant Sonangol. She has a reputation as a slick operator, has interests that range from telecoms, real estate and diamonds and is considered as an accomplished businesswoman in in her own right.

She has, in the words of journalist Simon Allison, "shattered the glass ceiling of Africa's male-dominated business world" - but it is hard to separate the woman from the name.

When the news hit the streets that "Isabel" was to head up Sonangol, some people grumbled.

While Mr Da Silva reminded us of her track record in business, others view her appointment as part of an elaborate plan to shore up the Dos Santos dynasty and the powerful elite who have benefited from the oil giant's funds.

Sonangol is responsible for half of Angola's gross domestic product (GDP), but critics accuse it of being unproductive and opaque - a vast omnipresent entity whose coffers have been plundered by powerful oligarchs.

Isabel dos Santos:

Daughter of Angola's Jose Eduardo dos Santos

Studied electrical engineering at King's College in London

Appointed by her father as head of the state oil company, Sonangol

Named by Forbes magazine as Africa's richest woman, worth an estimated $3.3bn (£2.3bn)

Owns large stakes in many of Angola's strategic industries, including diamonds, banking, media and telecommunications, with large parts of her business empire based in Portugal

Owns 7% of Portuguese oil and gas company Galp Energia

Plans to privatise the oil giant to make it more productive and transparent do little to appease sceptics such as Rafael Marques, a human rights campaigner and journalist.

He questions how much Angola is really transforming.

"The oil crisis has exposed problems in the way our country is run," he says, and until that is addressed and Angola gets a properly functioning democracy, little will have changed.

"This skewed economy, which protects the wealth of a privileged few", he states bluntly, will continue to be vulnerable to external shocks and "foreign investors risk perpetrating that system of patronage".

Meanwhile, President Dos Santos's son Jose Filomeno de Sousa dos Santos, in charge of the Sovereign Wealth Fund, has also found himself in the spotlight.

The fund, designed to promote development for the poor through the use of oil revenues, is estimated to be worth some $5bn.

But it has been been dismissed by some as a device to launder money out of Angola.

An outbreak of yellow fever has hit Angola hard

The shadowy body has recently found itself the subject of documents leaked from Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca, with links to Swiss bankers again raising questions about transparency.

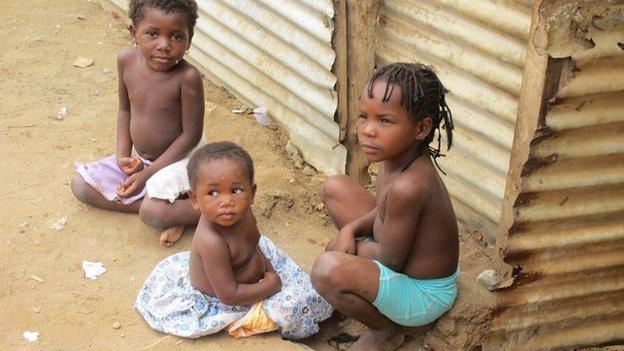

It is easy to be seduced by a city such as Luanda, but not far from the shimmering buildings are the shantytowns, where support for Dos Santos in next year's election cannot be guaranteed.

Here, the effects of the oil crisis are being felt hardest as food prices soar and access to dollars is limited.

People now speak openly about their irritation at what they consider a nepotistic clique that looks after its own.

It is where young people yearning for a change at the top vent their frustrations on social media.

Their parents may be tired of fighting, after 30 years of civil war, but the fact that there is access to social media gives them hope and a powerful platform.

Hope that future investors in a country oozing potential such as Angola will help lobby for a change of direction before it is too late.

- Published3 June 2016

- Published27 November 2015

- Published27 March 2015

- Published20 October 2014

- Published6 June 2016