Zimbabwe shutdown: What is behind the protests?

- Published

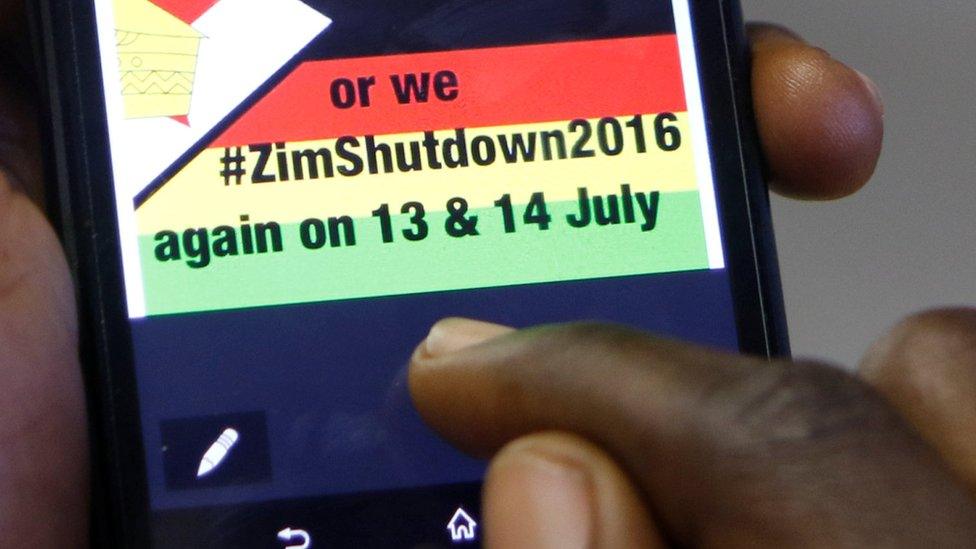

Zimbabweans are being urged on social media and the messaging service WhatsApp to observe a two-day national "shutdown" in protest at the government's alleged mismanagement of the country.

A one-day stay away was organised last week and led to a complete shutdown of schools, businesses and shops across the country.

It was the biggest strike action since 2005.

Why are people protesting?

Zimbabwe has run out of money.

Last month, all civil servants were paid late. Soldiers and police were paid after a two-week delay and teachers and nurses were among those who were only paid in the wake of last week's stay away.

Zimbabwe's week of protests

These salaries have to be paid in foreign currency as Zimbabwe abandoned its own currency in 2009 in order to stem runaway inflation.

As the country is importing more than it is exporting, it cannot pay its bills.

The coalition government formed with the opposition, which was in power from 2009 until 2013, halted the economic free-fall.

But things started to flounder again after President Robert Mugabe's Zanu-PF party won elections in July 2013 on a mandate of "indigenisation" and a promise to create two million jobs.

This has required all companies to cede economic control to black Zimbabweans.

With echoes of the country's land reform programme, which saw the seizure of land from some 4,000 white farmers, some detractors say this has discouraged much-needed foreign direct investment.

How bad is the situation?

Many people literally cannot afford to feed themselves. This has been exacerbated by a severe drought - the worst in decades.

Many Zimbabweans are relying on food aid this year

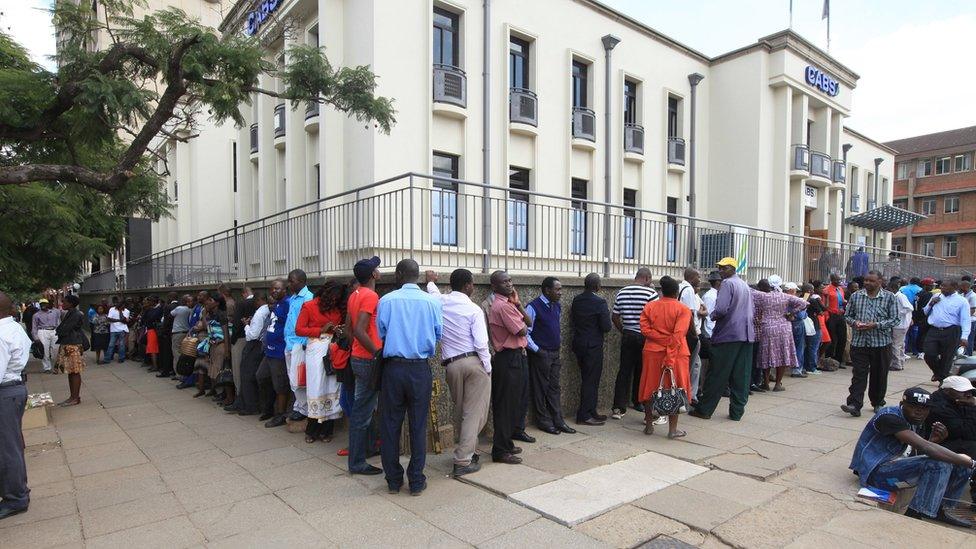

Even if Zimbabweans have money in their bank accounts, strict limits have been imposed on how much they can withdraw, leading to long bank queues.

With unemployment at more than 90%, many rely on cross-border trading to make a living.

In an attempt to stop money leaving the country, last month the government banned the importation of many goods - from coffee creamers and body cream to beds and fertiliser.

This led to demonstrations at the South African border and a warehouse belonging to the tax agency used to hold seized goods was set alight in Beitbridge.

Ten days later, police in the capital, Harare, had to use tear gas and water cannons to break up a protest by minibus drivers who were angered at constant harassment at roadblocks by officers demanding bribes.

Is there a plan to kick-start the economy?

The government wants to introduce bond notes as a cash substitute. They are to be pegged to the US dollar and would have no value outside Zimbabwe.

Zimbabweans can spend all day in a bank queue

Many Zimbabweans are sceptical about this and do not trust the scheme backed by the central bank governor and a $200m (£151m) bond facility from the African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank).

Memories of hyperinflation, when the highest denomination was a $100 trillion Zimbabwean dollar note - and prices would go up by millions from one hour to the next - are still fresh.

They fear that within months, the specially designed two, five, 10 and 20 dollar notes would have very little value - and as one market trader put it "wouldn't even buy a sweet".

It has not helped that the announcement of the bond notes came shortly after Mr Mugabe revealed that $15bn of the country's diamond wealth had been looted - something he blamed on foreign mining firms but which many Zimbabweans find hard to believe.

Who is behind the protests?

Pastor Evan Mawarire is using the Zimbabwe flag to rally for change

Charismatic pastor Evan Mawarire began a social media movement in May under the hashtag #ThisFlag, when he spontaneously posted a video online, expressing his frustration at the state of the nation.

It went viral and spurred him to continue urging Zimbabweans to find their voice and demand accountability from their government.

His outspoken videos in English and Shona are careful to say that non-violence is key, but other agitators are not so guarded.

Younger activists under the banner Tajamuka, meaning "we strongly disagree", are less moderate.

Shutdown activists' five demands:

Pay civil servants on time

Reduce roadblocks and stop officers harassing people for cash

President Robert Mugabe should fire and prosecute corrupt officials

Plans to introduce bond notes to ease a cash shortage should be abandoned

Remove a recent ban on imported goods.

Its supporters are young men who are fed up of waiting for jobs. Their brazen approach is similar to that of "Occupy Africa Unity Square", a group founded by Itai Dzamara, an anti-corruption activist who disappeared in mysterious circumstances last year.

Another agitator is young politician Acie Lumumba, who was recently expelled from Zanu-PF because of his vocal criticism of the government. He has recently launched his own party, and publicly insulted the 92-year-old president, saying: "You have never really seen Zimbabweans angry so here is the red line… I have drawn the line."

What happens next?

There are bound to be more arrests, the pastor has already been charged with inciting public violence. The authorities are determined to find those activists sending out the messages on WhatsApp.

Protests are likely to continue if civil servants are not paid on time. Churches and women's groups also appear to be joining in criticism of the government - and young people feel they have nothing to lose.

Supporters of President Mugabe blame Western sanctions for the country's problems

According to the Financial Times, external, the government is hoping to negotiate an emergency loan to pay off arrears totalling nearly $2bn with the World Bank, African Development Bank and IMF.

This would allow the country an emergency injection of funds from these institutions.

At the moment, South Africa is in talks with Zimbabwean officials over the import ban and some have suggested that switching to the South African rand as the currency of choice would also help boost the economy.

But to date Zimbabweans have been reluctant to hold the rand because of its falling value.

Another option would be to reintroduce its own currency and peg it to the rand, external, like in Lesotho and Swaziland. But that may dent national pride and signal a loss of financial independence.