Why elephants are seeking refuge in Botswana

- Published

"We've been seeing carcasses of elephants, some four months old, some less than a week old" reports Alastair Leithead, flying over Botswana

Elephants are everywhere - under the shade of trees, drinking by the river or playing at the few remaining waterholes in the drought-parched landscape.

Botswana has more elephants than any other country in Africa - 130,451 to be precise. At least that's the estimate given by the Great Elephant Census.

Sadly, hundreds of them have now probably been killed since the survey was done.

Botswana may be their last place of refuge on the continent, but poachers are already breaching its vast borders in their pursuit of ivory.

After two years spent flying half a million kilometres across 18 African countries, the Great Elephant Census (GEC), external results have been released and they don't paint a positive picture.

Fitting a tracker on a large elephant is a risky operation

In seven years, 30% of Africa's elephants have disappeared. At the current rate of decline, half the continent's remaining pachyderms will be gone in just nine years.

These are the headline findings from the first pan-African survey of savannah elephants, funded for $7m ( £5m) by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen.

It identified Tanzania, Mozambique, Angola and Cameroon as some of the worst affected areas.

"Of the 18 countries that we flew over, the GEC estimated 350,000 savannah elephants," said Dr Mike Chase, from Elephants Without Borders, external in Botswana, who was the principal investigator.

"Since 2007 Africa has lost 144,000 elephants, primarily due to the ivory poaching crisis. Each year we are losing nearly 30,000 elephants."

It's not easy counting all of Africa's elephants, especially in Botswana where there are so many.

Kelly Landen, also with Elephants Without Borders, has spent hundreds of hours 300 feet (90m) above the ground, peering out of a small plane and counting every elephant she saw between two wands precisely fitted to the wing.

Counting Africa's elephants from the air

"On each side of the plane we have a camera set up, so when we are counting we take several photographs and then we double-check and re-count afterwards in case we have missed a calf," she said.

The area is split into sections, or transepts, and the plane flies back and forth like a lawn-mower cutting the grass - turning at each end to ensure nothing is missed.

"The methodology is very robust and very strict. It was refined with a group of aerial survey experts. The numbers are extrapolated by the science," said Kelly Landen.

A statistical formula is used to estimate the total number of elephants in each landscape from the sample survey.

As well as counting live elephants, they also took note of every carcass, and in some places there were many.

Elephants clearly have a cognitive ability to understand where they are threatened

In parts of northern Cameroon the census found eight dead elephants for every 10 live ones. With only 148 left, scientists believe they will soon be locally extinct.

"There were days on the Great Elephant Census when I thought the only good I was doing was recording the disappearance of one of the most remarkable animals that walks this planet, but we have to be hopeful," said Dr Mike Chase, standing next to a newly discovered carcass.

But it's hard to be hopeful with the aerial survey data, and the evidence from the tracking collars they use to follow herds across the last great trans-frontier range in southern Africa.

Elephants Without Borders was set up to help governments protect the animals that wandered across Botswana, Namibia, Angola, Zambia and Zimbabwe, but there's now little they can do.

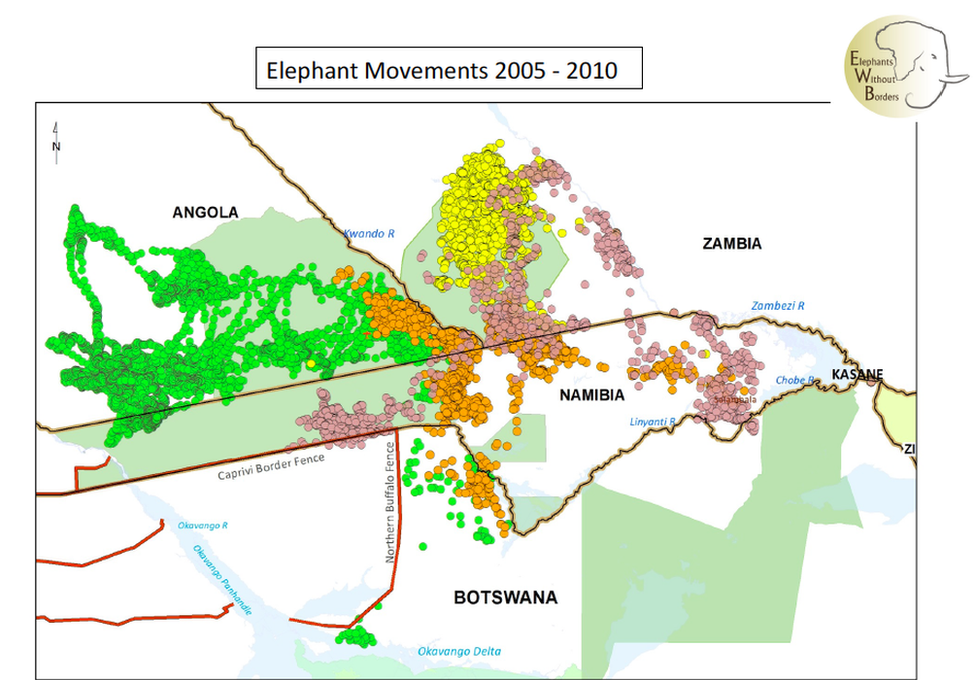

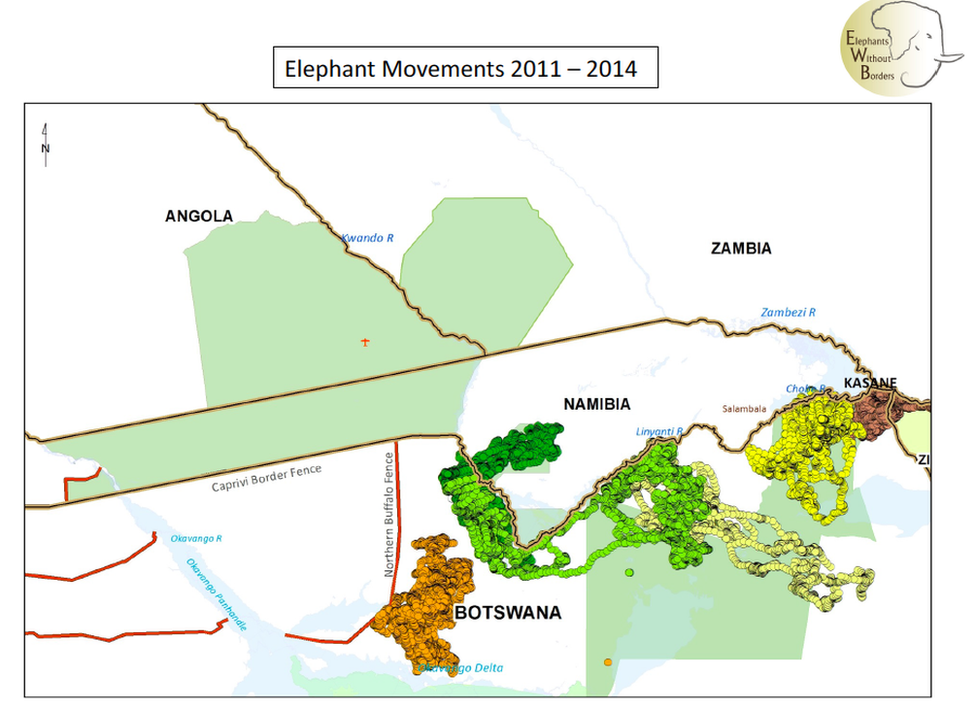

The satellite data shows how the animals are avoiding places where they are in greater danger.

How to put an elephant to sleep

Fitting a tracker on a large elephant is a risky operation.

First a vet has to find a safe place to dart the animal with anaesthetic, so it won't be hurt as it falls when the drugs take effect.

Then the team has to work quickly to attach the collar before injecting an antidote and then watching from a safe distance as the elephant gets back on its feet.

"We are housing a lot of refugee elephants in Botswana," the country's national parks director admits

The data is invaluable - and has given a remarkable insight into just how smart, and how threatened, these huge animals have become.

While elephants used to roam quite happily across international borders, the influence of poachers in Angola, Zambia and Namibia now limits them to Botswana.

"Elephants clearly have a cognitive ability to understand where they are threatened and where they are safe and in this case they are seeking refuge and sanctuary in Botswana where they are well protected," said Dr Chase, who admitted there wasn't room for them all.

Even without the worst drought in 30 years, Botswana can't cope with so many elephants.

Hunting has been banned here and even though the species is in crisis, culling is now being discussed.

"We are housing a lot of refugee elephants in Botswana," said Otisitswe Broza Tiroyamodimo, director of the country's Department of Wildlife and National Parks.

"Currently the number of elephants is so high per square kilometre that it puts a lot of pressure on the environment."

The huge human population growth across Africa is fast encroaching on areas where these huge animals can roam, and is increasing conflict with villagers.

The cosy pretence that Botswana's elephants are well protected has been completely blown out of the water

But at the moment their biggest threat is from the poachers and traffickers serving Asia's insatiable appetite for ivory.

Flying low over the floodplain which marks the border between Botswana and Namibia, that threat is clear

In the last few weeks Elephants Without Borders have discovered at least 21 fresh carcasses - the first major poaching incidents recorded inside Botswana.

"The cosy pretence that Botswana's elephants are well protected has been completely blown out of the water," he said through the helicopter headset.

"It's the last thing I expected to see and it becomes a lot more personal when it happens in your home country."

Carcass after carcass was scattered along the river - their faces hacked away to remove the maximum amount of ivory.

Soldiers do patrol the border - Botswana takes poaching very seriously - but the distances are vast, the financial returns for traffickers huge, and the risks to Africa's last remaining elephants increasing by the day.

- Published31 August 2016

- Published28 April 2016

- Published28 April 2016