Is private education the answer to Uganda’s ailing public schools?

- Published

Bridge international calls itself the world's largest education innovation company

Uganda's public education system is reeling from absent teachers, poor facilities and high dropout rates. Despite these challenges the country's ministry of education is pushing to close a chain of low-cost private schools, which says it is trying to offer solutions to these challenges.

A few minutes off the highway skirting the northern side of Kampala, we go down a dirt path, in a neighbourhood of bare-brick buildings with corrugated iron-sheet roofs.

The Bridge International Academies campus at Nsumbi, Nansana town in Wakiso district in the central region of Uganda, would blend right in, were it not for its bright green iron-sheet walls and roofing.

The half-built brick walls and wire mesh on the front give the school complex the look of a farm house.

A notice on a chalk-board at the gate reminds parents to pay at least half of their children's school fees, which range from $14 (£11) to $23 (£18) per three-month term.

The school follows Uganda's public education system of seven years in primary school, with children starting from the age of six.

Uganda's education crisis in numbers:

68% of students do not finish primary education

78% of new teachers failed a basic maths test and 61% failed a basic literacy test

29% of teachers absent during the week

Sources: Ministry of Education, 2014, Uganda National Examinations Board, 2015, Uwezo, 2015

Pre-installed lessons

The tuition fees here range from $14 (£11) to $23 (£18) per three-month term

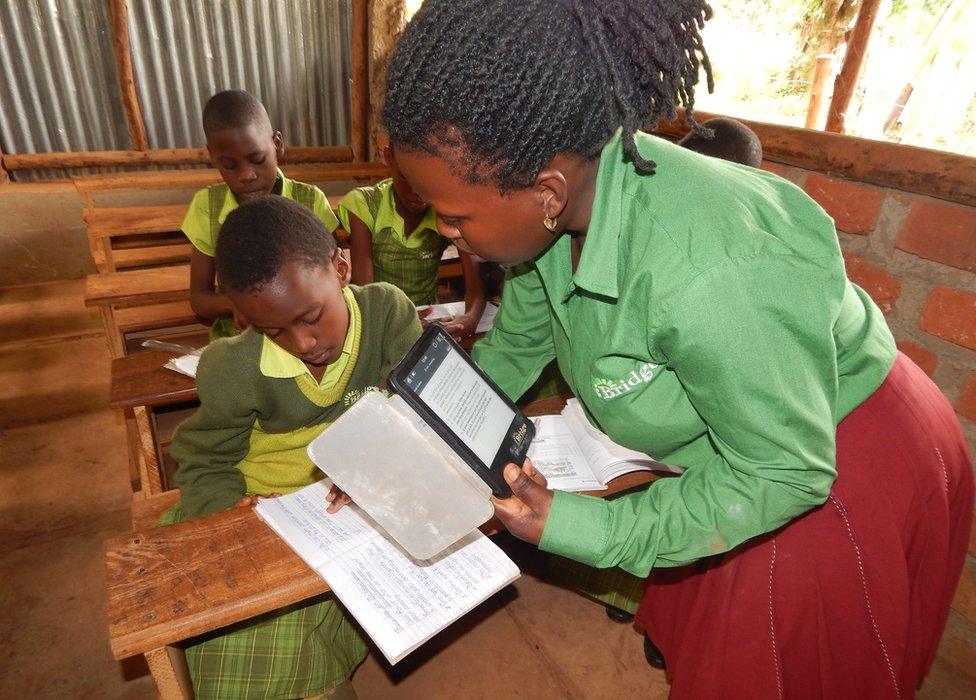

When we arrive, the primary five class are in the middle of a social studies lesson; learning about forests and their use as a habitat for animals. Answers are shouted out in chorus, on the teacher's cue.

The lesson is scripted, the teacher seeming to recite every line. There is a set of signals for teacher-pupil interaction; her snap of the finger signals to a pupil to ask a question, or give an answer.

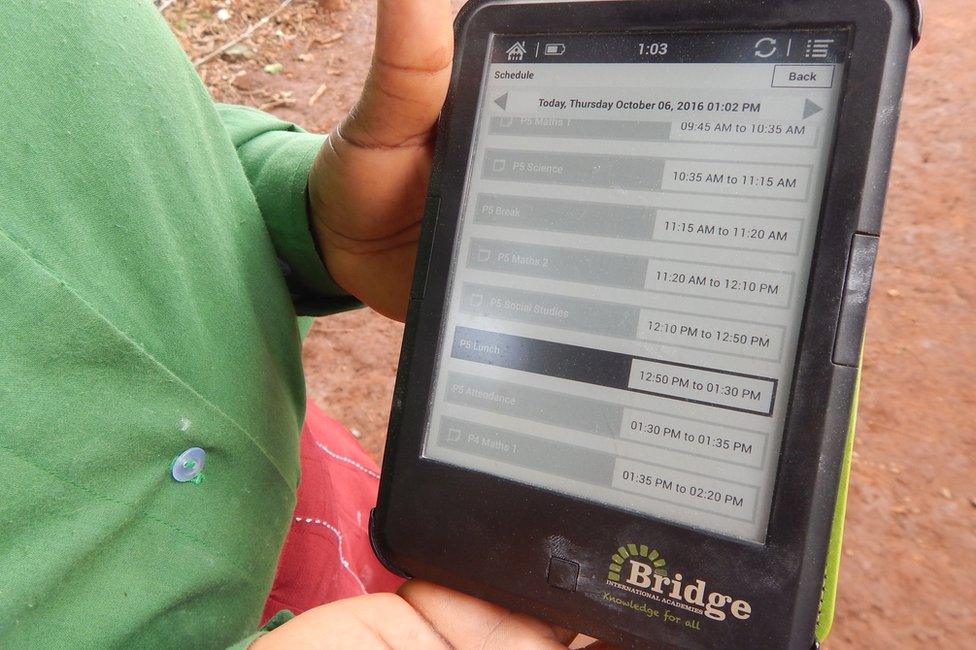

All that comes pre-installed in an e-reader, or a teacher computer.

"The tablet computers simplify our work. There is no need of writing up lesson plans," says Immaculate Nagawa, an English and Social Studies teacher.

"But we are closely monitored. We have preparation books which we fill in every morning.

"Some of the text books on the market have inaccurate information, but we don't fall victim to that because of the pre-installed content."

The expansion of the schools

Lessons are pre-installed in a tablet computer

I ask 10-year-old Alexa Rebecca Nakato what she thinks of this mode of teaching.

"The subjects are the same as my former school. But there we used to take down a lot of notes. I find the teaching method at Bridge very simple," she says.

Paul Kevin, her classmate, says his parents favoured the school so he could learn Kiswahili, East Africa's lingua franca.

As I move around the campus, I start to wonder whether it's all work and no play here, as even the queue for lunch seems to be managed with military orderliness.

In 2009, Bridge International opened its first academy in Mukuru, a slum in Kenya's capital, Nairobi.

The US-founded company, which aims to lower the cost of access to "quality education", now runs 405 schools in the country.

It also operates in India and Nigeria, and in January entered into a partnership with the Liberian government to run its primary schools.

The education venture opened its first school in Uganda in 2015 and just 18 months later operates 63 primary schools, with 12,000 pupils.

Why close the schools?

Pupil numbers have risen quite fast

But the school has courted controversy elsewhere.

In Kenya, the teacher's unions and non-governmental organisations have publicly called for the closure of the academies, saying that the schools were compromising teaching standards.

Bridge International, which calls itself "the world's largest education innovation company", receives funds from the International Finance Corporation of the World Bank, the Bill Gates foundation, Mark Zuckerberg's education venture and other organisations.

The UK's Department for International Development (DfID) also funds Bridge International, a situation that has been criticised by the UN, external because it is supporting a for-profit company.

A DfID spokesperson said it did not fund the Bridge Academies in Uganda and that: "When state provision is not delivering for the poorest, we work with low-cost privately run schools to provide an education to children who would otherwise get none."

In Uganda, the education ministry ordered the closure of the schools in July, citing:

Lack of a clear curriculum

Recruiting non-qualified teachers

Substandard school buildings

Poor sanitary facilities

The ministry declined to comment for this report.

Children learning under trees

Andrew White, the country director for Bridge International in Uganda, says that schools could not operate if they were run as a charity:

"The money is like a soft loan and there is an expectation of a return in future. Bridge is not an NGO. The money we use to operate comes from the pockets of parents."

He also denies suggestions that teaching is low quality, or is over-reliant on technology.

The half-built brick walls class at Nsumbi

"We have a residential program, where our teachers go through intensive training before they're deployed. Over 50% of our teachers are graduates of government teacher-training colleges.

"The integration of information technology in our teaching may look a bit different, but we're teaching the Ugandan curriculum."

He also argues that their buildings, which the education ministry has found wanting, were inspected and approved by the local District Education and Infrastructure Committees.

But if quality education is measured through bricks and mortar, then the government should not be criticising other educational providers.

Reports abound in the local press of public primary schools where lessons are conducted under trees or the children use anthills for desks.

Mr White said Bridge had a system that addresses one of the biggest problems in Uganda's public school's - teacher absence:

"Bridge has a computer system which will notify us if a teacher fails to show up for lessons. And we have a pool of substitute teachers. We can quickly deploy a substitute when we get the notification," he says.

The ministry complained about poor sanitary facilities, which Mr White says are basic ventilated pit latrines as "used in many schools in Uganda".

Twaweza, an education assessment NGO working in East Africa, found that children in Uganda's public schools aged eight-12 were unable to answer questions set for those aged seven.

Court case

Bridge International Academies says on its website that it aims to educate more than 10 million children across a dozen countries by 2025.

Its managers in Uganda say they are willing to explore all lines of dialogue with the education ministry, which seems bent on teaching them a lesson.

The schools are open for the moment, following an injunction issued by the High Court in September. The court case is expected to come for hearing on 28 October.