Sudan civil disobedience: Why are people staying at home?

- Published

A Twitter user posted this photo saying it was of shops closed as part of the protests

Protesters in Sudan are holding a "day of disobedience". What is it and why are they protesting? BBC World Service Africa editor James Copnall explains.

What are the protesters doing?

Instead of taking to the streets or marching towards a ministry or the presidential palace to express their concerns, as they have done in the past, Sudanese protesters are doing something much simpler - staying at home.

Some students have not gone to their school or university; workers have not turned up at the office; even some government employees have not shown up for work. This tactic of "civil disobedience" has been tried before - in November the protesters held a three day "stay-at-home" strike.

Activists tweeted photos of empty streets and offices, particularly on the first couple of days. By day three, most people were back at work. But the protest was considered to be so successful that the "day of disobedience" is being repeated.

However, it appears as though fewer people are heeding the call to stay at home this time.

You can follow on social media with hashtags like #SudanCivilDisobedience and #Dec19Disobedience.

What are they upset about?

The trigger for these protests came last month when the Sudanese government imposed a fresh round of austerity measures - at a time when the economy is doing so badly that many Sudanese are struggling to make ends meet.

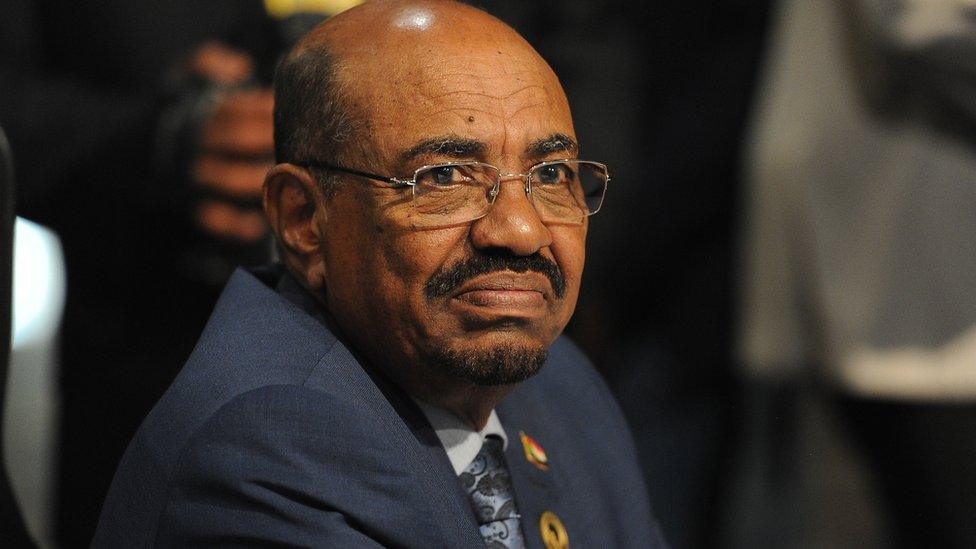

Sudanese President Omar al Bashir has dared protesters to take to the streets

The rise in petrol and diesel prices led to an increase in the cost of many basic goods, including medicines. The government eventually backtracked on medicines, because the suffering of sick people struggling to afford the drugs they needed provoked such anger.

For many - but by no means all - of the protesters, another motivation is dislike of President Omar al-Bashir and his government.

Since Mr Bashir seized power in a coup in 1989, Sudan has not known a day of peace and civil wars continue in Darfur, South Kordofan and Blue Nile.

Who is organising the day of disobedience?

This is a very interesting question and one which nobody seems to have an answer for. The initial call to stay at home came on social media, but no organisation or group has said it was responsible.

A Twitter user shared a photo of this nearly empty highway in Sudan

Instead it seems to have been the work of a number of social media users with no particular affiliation. A large number of bodies have backed the campaign, including opposition parties, cultural organisations and youth groups.

Even a major rebel movement, SPLM-North, has tried to throw its weight behind the demonstration. However most of the protesters seem sceptical of these attempts to join - or shape - their efforts.

How has the government responded?

These protests have clearly rattled the government.

Last week, President Bashir warned "keyboard activists" that they would not be able to overthrow his government and challenged them to take to the streets - a reference to the last major protests in the capital in September 2013.

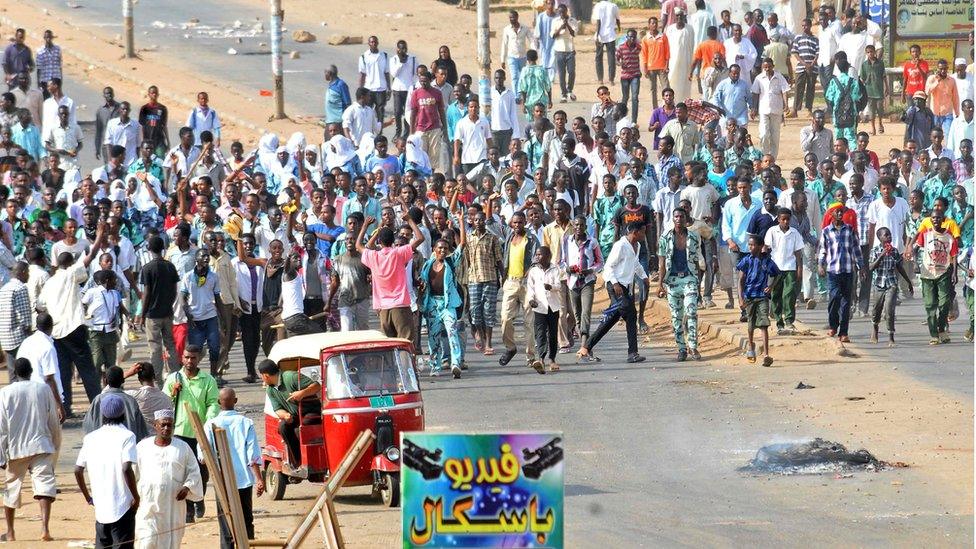

People in the capital Khartoum demonstrated against the government's economic reforms in 2013

The security forces used live ammunition to stop those demonstrations, which were also about austerity measures. Rights groups say as many as 200 people were killed.

This time round, the security forces have used tear gas to break up some demonstrations before and after the first stay-at-home days, and they have arrested several opposition politicians and stopped newspapers from printing stories about the protests.

The government insists it has no choice other than to impose the austerity measures, which have been recommended by the International Monetary Fund. The economy has been crippled by the secession of South Sudan in 2011.

When the South Sudanese declared their independence, they took with them three-quarters of the oil production, leaving a huge hole in Sudan's finances. The slump in the world oil price has not helped either.

But critics say the economic crisis is also a result of the government's political failures, including the ongoing civil wars, its insistence on spending so much money on the military and national security and the pervasive corruption.

How significant are these protests?

The civil disobedience campaign has invigorated activists and many who are opposed to the government. Some told me they felt a rare feeling of power - when they are more often used to helplessness - as they saw the empty streets and places of work the first time round in November.

The great strength of a stay-at-home campaign is that people can register their dissent with comparatively little risk. The security forces crack down hard on any street protests, but it is more difficult to stop people from expressing their dissatisfaction by skipping work.

Yet the form of the protest also underscores its limitations, as Mr Bashir himself said, keyboard activists and people sitting around in their homes are unlikely to topple him.

But fewer people have followed the disobedience day compared to November.

There are several possible explanations for this:

The government cancelled the rise in the cost of medicines, which had infuriated so many

The security forces had more time to work to stop people protesting

And some people seem to have been annoyed by the attempts of the opposition and other groups to take control of the campaign.

That said, these protests are highlighting the huge frustrations in Sudan and the economic crisis, which people are angry about, is perhaps the greatest threat facing Mr Bashir and his government.

- Published13 September 2023