West Africa - from dictators' club to upholder of democracy

- Published

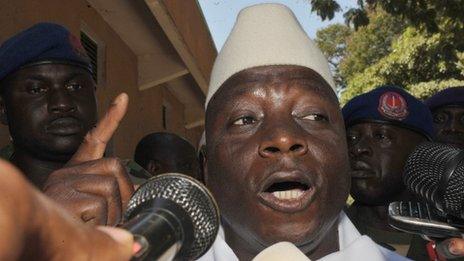

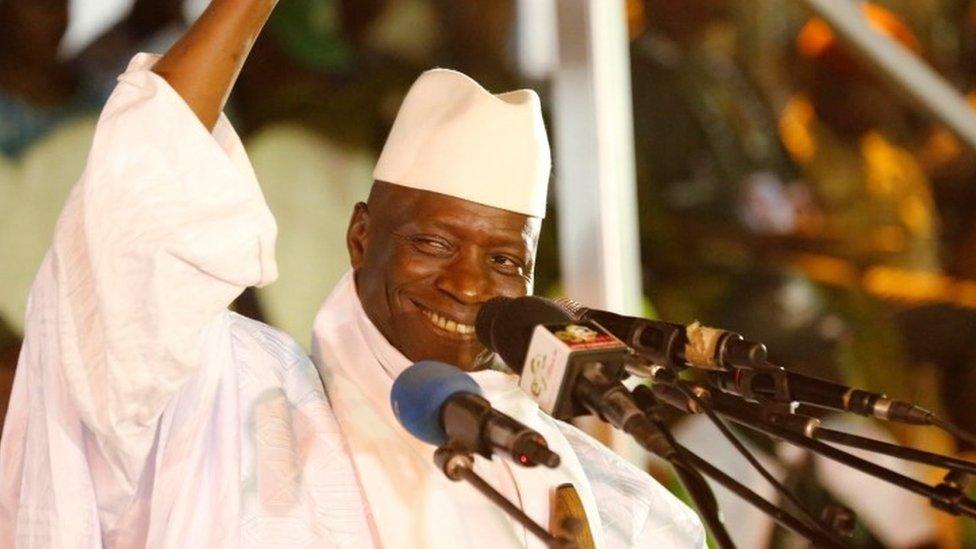

Yahya Jammeh appears to have secured immunity from prosecution

Former Gambian leader Yahya Jammeh failed to appreciate that democracy had taken root in West Africa. It left him on a hiding to nothing once he lost elections, writes Elizabeth Ohene.

If proof were needed that the political atmosphere had changed in West Africa, it came with the departure into exile last Sunday of the long-time leader of The Gambia.

Yahya Jammeh would want to put a spin on the circumstances of his departure, but the unvarnished truth is that he was forced out by troops from regional grouping Ecowas.

The Ecowas leaders had tried to talk him out of hanging on after losing the December elections, but when the talking failed, they resorted to language they knew Mr Jammeh would understand.

Time was when the most exclusive club in the world was the African heads of state club. It was not very easy to determine what the membership qualifications were, apart from the obvious.

Liberian President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf is one of only two women to have joined the African leaders' club

Members had an unwritten but sacred rule about never criticising each other for whatever they did to the citizens of their own countries. The "internal affairs of member countries" were off-limits and never came up for discussion during meetings of the continental or sub-regional meetings.

A country's prisons could be jammed with political prisoners and the head of state would be welcomed at African continental meetings and given a standing ovation for criticising "the racist South African regime".

For a long time, it was an all-male club and members called each other "my brother president". Indeed they still do, even though there have been two female interlopers in the past decade.

Members did not care very much how "the brothers" came to be heads of state. You could be elected to the position in dodgy elections, or in fairly conducted elections and then change the rules, you could assume the position through a coup d'etat. For as long as you could show you had firm control over your country, you were a "brother president".

It wasn't clear if members were required to pay dues but membership appeared to be for life. During the 1970s, 80s and 90s, the west African part of the continent had a poor reputation. At one stage, only one country, Senegal, had not endured a military regime.

West Africa had become a region known for political instability and leaders who did not want to leave. The chances of a peaceful transfer of power were zero.

It is difficult to determine exactly when things began to change but gradually fortunes changed for the personalities who had appeared to be perpetual opposition figures.

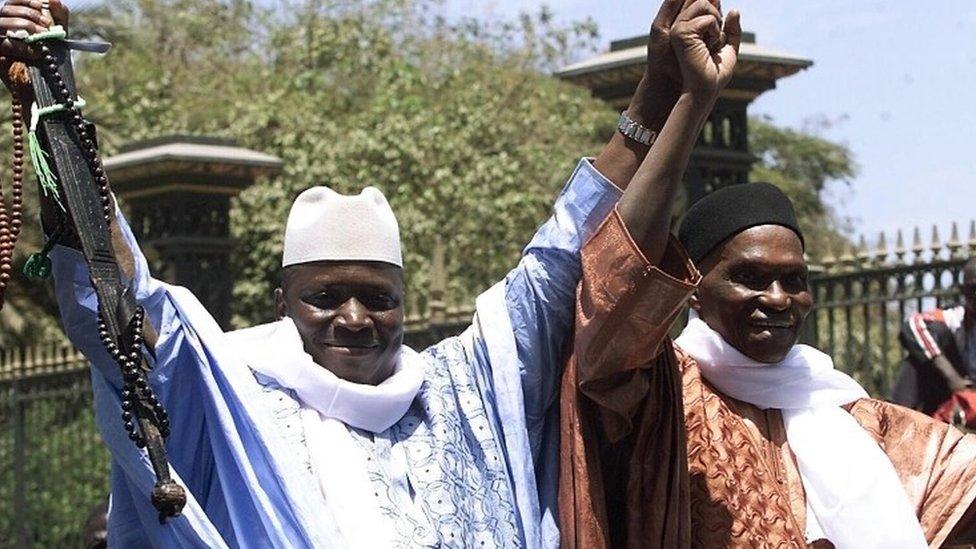

Abdoulaye Wade (r), seen here with Mr Jammeh in 2002, was one of the first opposition leaders in the region to gain power

Abdoulaye Wade, Senegal's perennial opposition leader, won a famous victory in 2000 and became president, sending into opposition for the first time the party that had governed the country since independence. He was one of those who broke the mould.

As it turned out, President Wade then appeared to become afflicted by the West African disease and tried to prolong his stay in office beyond his official welcome. He lost to Macky Sall in the 2012 elections and did concede, although ungraciously.

Former opposition leaders now in power in West Africa:

Patrice Talon, Benin

Nano Akufo-Addo, Ghana

Alassane Ouattara, Ivory Coast

Muhammadu Buhari, Nigeria

Macky Sall, Senegal

Ernest Bai Koroma, Sierra Leone

In Ivory Coast, an equally perennial opposition figure, Laurent Gbagbo, became president in 2000. He is currently at The Hague before the International Criminal Court since his arrest in 2011 after trying to retain power after an election loss in late 2010.

Those elections were won by Alassane Ouattara, another who had unsuccessfully stood in several elections.

The biggest triumph came over in Nigeria, the impossible happened in 2015 when the incumbent, President Goodluck Jonathan of the PDP, the party that had been in power since the return to constitutional rule in 1999, lost to opposition candidate Muhammadu Buhari.

Sitting presidents simply don't lose elections in Nigeria and the PDP had looked immovable. But President Jonathan graciously conceded and presided over a smooth transition of power.

The deployment of Senegalese troops by Ecowas was a language Mr Jammeh could understand

In Ghana, transitions of power had become more commonplace, with the governing parties ousted in both 2000 and 2008, as well as 2016.

In fact, on 9 December, just about the time that Mr Jammeh was reversing his initial decision to accept defeat, Ghanaian President John Mahama was phoning Nano Akufo-Addo to congratulate him for winning after losing the two previous contests.

So the idea of conceding has become accepted and expected practice in West Africa. Ghana and Nigeria have even voted out one-term presidents and the heavens haven't caved in.

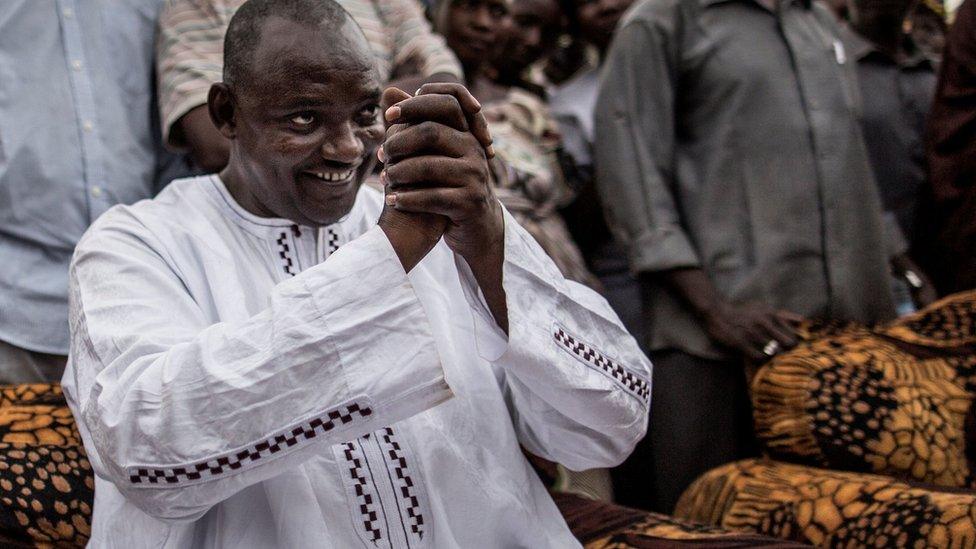

Sengalese President Macky Sall (r) gave Adama Barrow a red-carpet send-off when he returned to The Gambia on Thursday to take power

Mr Jammeh had already become quite an embarrassment to his colleagues in the African leaders' club. His longevity in office did not give him the senior positions to which he aspired. Three times he tried to become Ecowas chairman and three times he was thwarted.

There were few leaders who would openly support him in his claims to be able to cure Aids or his boast that he could rule The Gambia for a billion years if Allah wished.

Having conceded, and then un-conceded, Mr Jammeh was on a hiding to nothing. Ecowas mediators came to Banjul - one, Mr Buhari, a beneficiary of a one-term president who had conceded, and another, Mr Mahama, who had just conceded himself.

They were never likely to look on Mr Jammeh with sympathy. A few years ago, Mr Jammeh might have been able to bluff his way through it and hold onto power.

But not today, with so many West African presidents being former opposition leaders themselves.

The only lingering uneasiness is over the terms of Mr Jammeh's exit deal. It would appear from the joint statement issued by the UN, AU and Ecowas that Mr Jammeh was promised immunity from prosecution in return for leaving.

As details emerge of alleged human rights abuses committed under his rule, the strength of that promise may yet be tested.

- Published26 January 2017

- Published19 January 2017

- Published23 January 2017

- Published22 January 2017