Fespaco 2017: Six things about Africa's biggest film festival

- Published

From a timid start in 1969, the Pan-African film and television festival (Fespaco) has today grown into the leading cultural event in Africa.

It takes place every two years in Burkina Faso's capital, Ouagadougou, with the stated aim of promoting African cinema.

The event is loosely modelled on the Cannes Film festival. Like Cannes, it:

offers an opportunity for film enthusiasts to binge-watch cinematic productions;

brings professionals together to promote their work and discuss industry-related challenges;

celebrates excellence by handing trophies to top industry talents.

This year's edition has been going on since last Saturday and is wrapping up this weekend. Here, are six things you need to know about the festival.

Going digital

Fespaco is a unique event where African film enthusiasts get to see as many African productions as possible

Fespaco received almost 1,000 submissions for 2017, far more than previous years.

The festival used to be very select with regard to which type of production is acceptable and who could compete.

Films shot on budget-intensive celluloid were the standard and the official selection was open only to continental African directors.

The restriction was lifted a year ago. So now, digital films and films from directors from the African diaspora qualify for consideration in all categories.

The large number of entries meant submissions were put through a sift, and ultimately 150 films were retained by the organisers.

But many directors are in Ouagadougou to promote work which does not feature in the official strands - so a total of 200 films are being screened during the festival.

'The African Storm'

No picture at Fespaco 2017 seems to be making as much a splash on the festival enthusiasts as The African Storm, a film by Beninese director Sylvestre Amoussou.

It features among the 20 films which are up for the top award - the Golden Stallion of Yennega, a trophy with a cash prize of 20,000,000 CFA francs ($32,000; £26,000).

The film tells the story of an African president who nationalises businesses run by racist, cynical Western executives.

"It's not an anti-European film, but a film against the governments of states that exploit us," Amoussou told the AFP news agency.

The subject matter of The African Storm is rarely tackled by African productions which are usually funded by Western donors under criteria that favour themes on a "miserable Africa", Amoussou says.

With the unusually provocative message it conveys, the movie seems to connect so well with its Fespaco audience.

Its screening on Wednesday was punctuated by applause and shouts of approval.

A Thomas Sankara Prize

A look back at former Burkina Faso President Thomas Sankara's time in power

When Ethiopian filmmaker Haile Guerima won the Golden Stallion of Yennega, Fespaco's top award, in 2009, he did not show up to collect the trophy in person.

Guerima had vowed he would not set foot in Burkina Faso for as long as President Blaise Compaore was in power.

Guerima's boycott was because he believed Mr Compaore killed Thomas Sankara in 1987 to grab power. Mr Compaore, who was ousted in 2014 by a popular uprising, denies the allegation.

Now Guerima might have more than one reason to set foot back in Burkina Faso for Fespaco. Not only is Mr Compaore no longer in power; but also a prize has now been created in honour of Thomas Sankara.

Praised by supporters for his integrity and selflessness, the military captain and anti-imperialist revolutionary, often nicknamed Africa's Che Guevara, led Burkina Faso for four years from 1983.

Be it through the red beret worn by firebrand South African politician Julius Malema, or the household brooms being wielded at street demonstrations in Burkina Faso, there are signs that Sankara's legacy is enjoying a revival.

The prize in his name has been created to promote that legacy.

Contenders to the award are not required to tackle a "revolutionary" theme - the winning production is picked for its artistic merit.

Heavy Security

Burkina Faso has been rocked by a series of attacks since 2014 and as a result Fespaco is taking place under heavy security

Security has always been stepped up in Ouagadougou during Fespaco, but none of the previous festivals has ever taken place under such heavy security.

Armed soldiers have been positioned at screening venues and crowded places to prevent the festival coming under assault.

Burkina Faso has been rocked by a series of attacks by Islamist militants over the last two years, with the deadliest so far killing 30 people in January 2016.

And as the festival was getting underway earlier this week, two police posts came under attack.

The attack prompted organisers to reassure the public over security.

"I call on all festival-goers to remain calm because security forces are doing their best to assure maximum security,'' said Marcel Pare, head of security for Fespaco 2017.

Reggae diplomacy

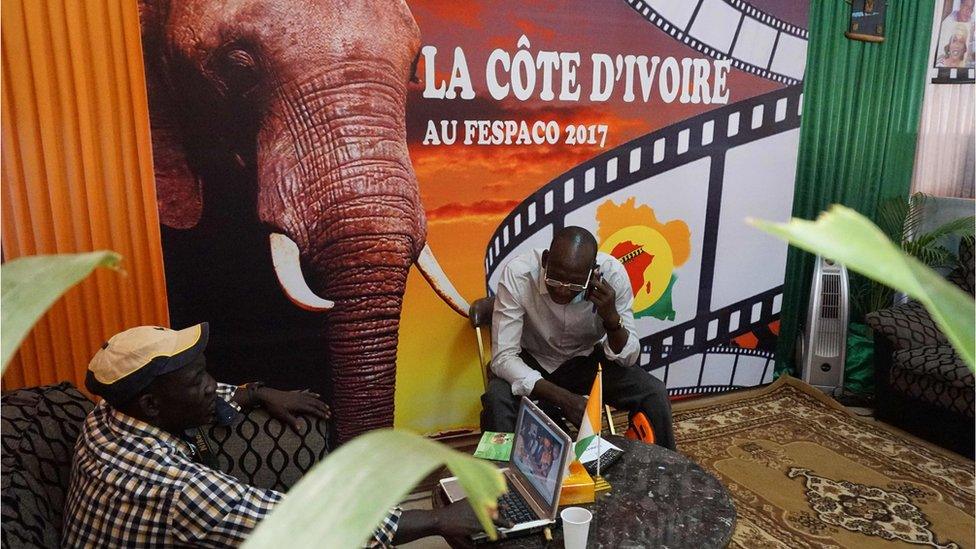

One of Ivory Coast's official stands at the Fespaco in Burkina Faso.

Every year, an African country is designated as "guest of honour" - this year, it is Burkina Faso's neighbour Ivory Coast.

Political tensions have been running high between Ouagadougou and Abidjan since former President Compaore fled into exile in Ivory Coast after he was ousted in 2014.

Honouring Ivory Coast through Fespaco is seen as one of many ways for officials in Burkina to reduce the tensions.

Ivory Coast's Alpha Blondy led the musical acts at the opening of the festival

Ivory Coast responded in style, with two Ivorian productions featuring in the festival's main competition.

But that is not all: Ivory Coast provided its mega reggae star - Alpha Blondy - as the lead act for the lavish performances which marked the opening ceremony of Fespaco 2017 last Saturday.

Haunted HQ?

Next to Fespaco's main building is an enormous structure which should have been the festival's major hub this year.

If the plan had been on-course, most films at the Fespaco would have been screened from purpose-built rooms within the structure.

Visitors could have gone to an African cinema museum inside the same building - in short, a lot was expected from it.

But there is a problem with "La Salle Polyvalente" - Fespaco's long awaited and delayed multi-function complex.

After it took many years to complete with delays blamed on mysterious accidents happening on the construction site, it later caught fire and work to restore it was not completed in time for this year's edition.

The multi-function complex of Fespaco is still unfit for occupation

That started a rumour which has it that the building is haunted.

La Salle Polyvalente was reportedly built on a sacred plot of land and the unhappy local residents would not let any use be made of the building.

Officially, that explanation is rubbished.

"A myth has been created," Baba Hama the longest serving director of Fespaco told AFP.

"Haunted? And how could I still be alive? Traditional authorities granted permission. Ceremonies of exorcism took place.

"The sacred wood had been spared through a careful delimitation. Plus in Africa, there is always an antidote for calming the spirits."

No matter how much officials try to put the rumours to rest, there is always a tale in Ouagadougou about some angry ancestors frowning upon the defiling art of the cinema and who would not let La Salle Polyvalente be put to its intended use.

- Published26 February 2013

- Published1 March 2013

- Published13 May 2015