Somalia ship hijack: Maritime piracy threatens to return

- Published

The latest hijacking off the Somali coast could mark the return of a lucrative business

The hijacking of a merchant fuel tanker by pirates off the Somali coast this week has sent shockwaves through parts of the shipping industry.

It is the first successful hijacking of a major commercial vessel in the Somali Basin since 2012 and is prompting debate over whether shipping companies have become complacent about the risk of maritime piracy.

The MT Aris 13 was travelling from Djibouti to Mogadishu on 13 March when, instead of giving the Somali coast a wide berth as advised, it took a short cut between the tip of the Horn of Africa and the Yemeni island of Socotra.

Somali pirates then ambushed the vessel just 11 miles (17km) from shore with two fast speedboats, known as skiffs, while aiming their weapons at the crew.

The vessel and its crew of eight Sri Lankan seafarers have now been seized by the pirates and are being held pending either ransom negotiations or a rescue attempt by the regional Puntland authorities. This brings to 16 the number of seafarers currently being held by Somalia-based pirates, the remaining eight being Iranians.

A 'sitting duck'

"For a vessel passing that close to the coast of Somalia without armed guards shows a level of complacency," said a spokesman for Neptune Maritime Security, which is currently running armed protection teams on around 70 vessels this month as they pass through the area of the western Indian Ocean known as the High Risk Area (HRA).

Employing armed teams, usually former servicemen, is seen by many shipping companies as prohibitively expensive. Shipping industry analysts say many vessels, especially those with a high freeboard (the vertical distance between the surface of the sea and the deck) have simply been speeding up to avoid capture. This is part of what is known as Best Management Practice, or BMP4.

Although pirates have, in the past, been incredibly adept at scaling the sides of big ocean-going vessels while in motion, this becomes very hard to do at speeds of 15 knots or more, especially if the captain takes evasive action, creating an unpredictable bow wave that can sink the pirates' skiffs.

A protection team scan the southern Gulf of Aden for pirates while passing through the High Risk Area

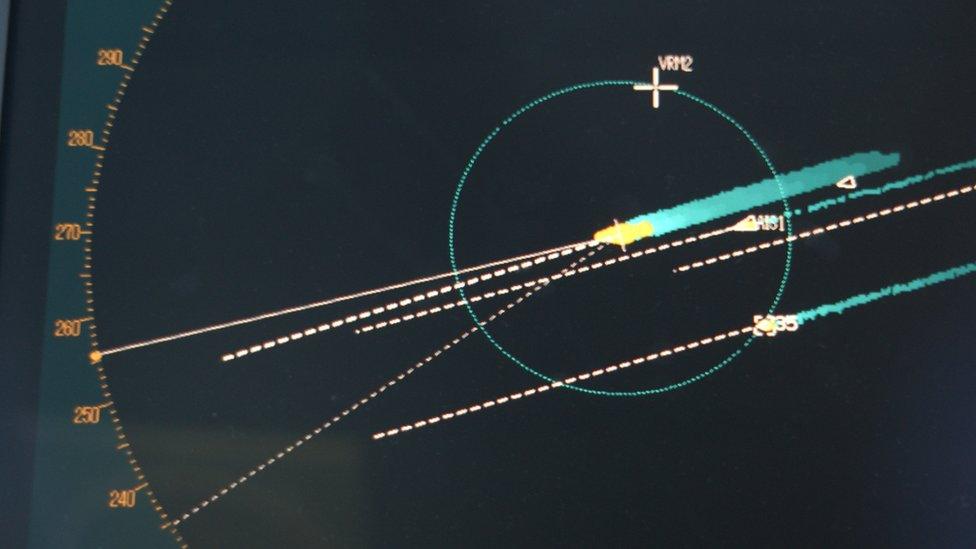

Radar on board the protection team's vessel monitors suspect vessels

The EU anti-piracy naval force off the coast of Mogadishu in 2013

In recent years the European Union and other nations, including China, have mounted naval patrols to deter Somali piracy and escort convoys along the coast of Yemen. But the area is so vast that their ships were rarely able to reach a vessel in distress in time. Once pirates were onboard it became a hostage situation which most naval vessels' rules of engagement prevented them from getting involved in.

"The navies' presence is good," says John Steed from the seafarers' welfare group Oceans Beyond Piracy, "but the primary factor in deterring Somali piracy has been the presence of armed guards onboard, along with best practice like speeding up," he added.

The ship that was captured on Monday had a low freeboard and was travelling so slowly that it was, he says "almost a sitting duck".

'Dubious' licences

So will this latest hijacking be a wake-up call that prompts more precautions being taken at sea or will it signal the start of a new wave of piracy?

Worryingly, the factors that drove many Somali coastal fishermen to become pirates nearly a decade ago are still there. Somalia is currently in the grip of a famine and poverty is widespread; there are few employment options for young people.

There is massive and growing local resentment at the poaching of fish stocks off the coast by Asian trawlers. According to Oceans Beyond Piracy, some foreign vessels have "dubious" licences issued by officials in Puntland, but the local people never get to see any benefit from them.

Return of a lucrative business

The high point in Somali piracy came in 2010, both in terms of vessels hijacked and the number of seafarers taken prisoner for ransom. Soon after that, shipping companies began placing armed guards onboard who would "show weapons" to circling pirates and if necessary fire warning shots to ward them off.

This effectively broke the pirates' business model as, until then, they had been able to approach a ship, often at dawn after a night of chewing the narcotic qat leaf, open fire on the bridge to scare the captain into slowing down and stopping, and then they would board it using ladders.

They would then hold the vessel, its crew and its cargo for ransoms of millions of dollars.

After 2010 they were no longer able to do this with impunity. But now that news will have spread that many vessels are not carrying that armed protection there are concerns that the lucrative business of Somali maritime piracy may be set to return.

- Published15 March 2017