Would a legal market for rhino horn deter poachers?

- Published

Experts say legal trade in horns will not deter poachers

It's now legal to trade rhino horn in South Africa after the highest court in the land lifted an eight year ban on a technicality.

The domestic sale of rhino horn will be allowed to resume, but only with a permit and only within the country's borders.

There's not traditionally been much demand for rhino horn in South Africa, so there a question mark over just how much of an impact the ruling will have.

The biggest market for rhino horn is Asia, and an international treaty still prevents its export and sale to many countries.

But some big conservation organisations, such as the WWF, believe it will encourage the illegal trade, which causes the poaching of more than a thousand South African rhinos a year.

To trade or not to trade?

The Private Rhino Owners' Association, which backed the court challenge against the 2009 moratorium on the rhino horn trade, is delighted and believes it will help conserve the protected species.

To trade or not to trade? - be it rhino horn or ivory - is one of the big questions which divides the world's conservationists and wildlife protection groups.

And it's complicated.

"We as the private sector bought and own a third of the national rhino herd - more than 6,500 black and white rhinos," said Pelham Jones from the Private Rhino Owners' Association.

The biggest market for rhino horn is in Asia

"We have a huge vested interest in their conservation and have spent billions of rand protecting and managing our herd - 'sustainable utilisation' is in the constitution," he said.

And what he means is private owners want to remove and sell rhino horn to fund their conservation - and also to make profit.

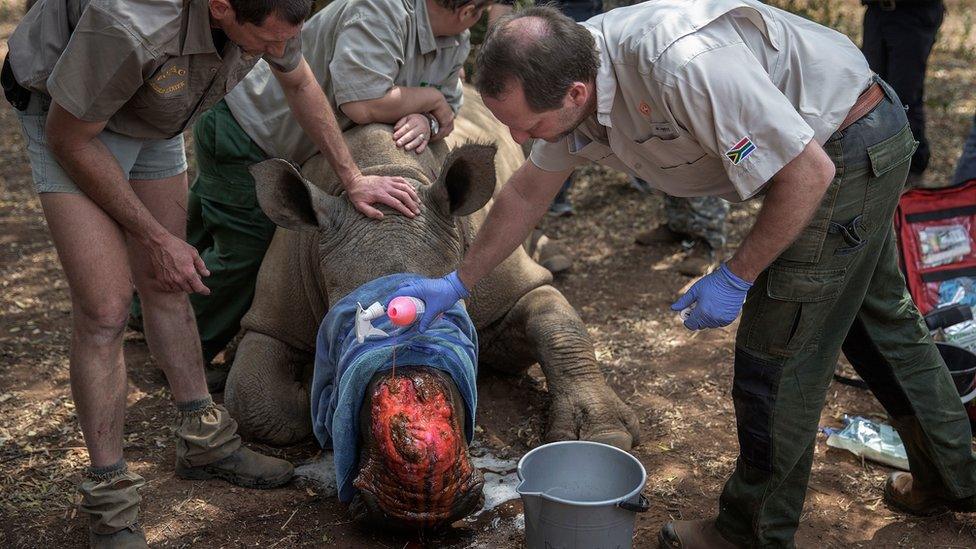

Painless process

The world's largest owner of rhinos is John Hume, who regularly 'harvests' rhino horn - cutting them off and storing them.

It's a painless process and the horns do grow back.

He has around 1,400 rhinos on his ranch in South Africa and a stockpile of perhaps five tonnes of horn.

At a market price of $90-100,000 a kilogramme he is sitting on a fortune - if he can get his produce to market - to Asia, where it is used as a medicine and to make cups and jewellery.

There are said to be more than 6,500 privately-owned rhinos in South Africa

But even with the lifting of a ban on domestic trade, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (Cites) prevents its sale abroad.

"We will set up our own central selling organisation," said Pelham Jones, who believes commodities speculators will buy rhino horn in South Africa, and that so-called 'blood horns' - illegally poached horns - won't enter the market.

"There are a lot of unknowns here, but everything else that has been tried to prevent poaching has failed."

'Blood horns'

But those opposing the trade say it will muddy the waters when trying to stop the illegal trafficking of rhino horn.

"We are concerned by the court's decision," said Dr Jo Shaw, manager of WWF South Africa's rhino programme.

"Law enforcement officials simply do not have the capacity to manage parallel legal domestic trade on top of current levels of illegal poaching and trafficking," she said.

"We worry about the resultant impacts of the laundering of so-called 'blood horns' upon our wild rhino populations."

More than 1,000 rhinos a year are poached in South Africa

Dr Shaw accepted the value to conservation of captive breeding, and that new sources of income were needed to protect the species, but said opening up trade was too great a risk to their dwindling numbers.

The South African government placed a moratorium on rhino horn trade in 2009 after evidence showed the legal domestic trade was leaking into the illegal international market.

But by not consulting widely enough on the issue with interested parties, it left itself open to the legal challenge which the Constitutional Court has just upheld.

The Minister for Environmental Affairs, Dr Edna Molewa, said trade would not be allowed without government approval.

'It's going to be heading for Asia'

Those selling rhino horn - and those buying - will both require permits which can be audited at a later stage to ensure the horns have not been sold on.

Draft legislation from the South African government suggested some limited export of rhino horn might be allowed for "personal use" - two horns per person, per year.

But Esmond Bradley-Martin who has researched the price of ivory and rhino horn for decades, said he feared the lifting of the ban could increase corruption and the power of the cartels.

"I can't see this working in the future without improved law enforcement - there is almost no demand in South Africa, so it is going to be heading to Asia," he said.