South Sudan famine: How the UK delivers lifelines from the sky

- Published

Planes drop aid sacks into famine-hit areas of South Sudan

In the dusty, baking emptiness of Leer in South Sudan, bags of British food aid fall from the sky to relieve the hunger below.

It is here in the north of the country that the United Nations has declared a famine. It is here that the fighting between government and rebel forces has driven so many into hunger and homelessness. And it is here that UK aid is being carefully targeted from the air.

To watch these bags of cereal and pulses and food substitutes pour from the bellies of ageing Russian transport planes that have been hired by the aid agencies is to witness an absolute good. For without it, more people in this war-ravaged, hunger-stricken country in central Africa would starve to death.

I watched the Ilyushin planes lumber slowly into view alongside Priti Patel, the International Development Secretary, who had travelled many hours to see what impact the money she had authorised was having on the ground.

Despite the controversy over her £13bn aid budget, Ms Patel insisted that Britain's humanitarian spending gave it influence in the world.

UK International Development Secretary Priti Patel inspects aid sacks that have been dropped by plane

First the planes practise a low pass over the drop zone, marked by a large white cross. They make another wide circuit to let nearby villages know an aid delivery is on its way. And then, at around 300 metres above the ground, they begin to drop their cargoes.

Each plane can carry about 30 metric tonnes of aid, about 600 sacks. They make three passes, dropping 200 sacks each time. These are not parachute-born crates, just individual bags hurtling towards the ground. Like some dreadful game of pass-the-parcel, each sack is bagged seven times to stop it exploding on impact.

To watch this, to see the gleam of hope in the eyes of those waiting below, is a moving experience. For many of them, without this aid, they would be forced to live off what nuts, leaves and water lilies they can forage, none of which provides adequate nutrition.

"UK aid is providing a much-needed lifeline to people who have been persecuted, driven off their homes, forced to flee," Ms Patel told me. "The aid that we are providing right now is the difference between life and death."

Yet the problem is this. Each plane contains food enough for only 2,000 people a month. The cost of the planes is astronomic and there are only seven in the region that the World Food Programme can operate.

There is a scarcity of available food aid because there are so many other droughts in the region. Each drop has to be negotiated with local community leaders and armed groups, whose permission is needed to ensure that any fighting is put on hold. The hungry will come only if they feel safe.

Any food drop in a government-held area has to be matched by one in territory held by the rebels

The distribution centre on the ground - a temporary, pop-up affair - can exist only for a few days before the security risks become again too great.

Any food drop in a government-held area has to be matched by one in territory held by the rebels. The amount of aid has to be roughly equal in size to avoid accusations that the aid agencies are taking sides.

A history of South Sudan in 105 seconds

In other words, this aid that falls from the sky may help people who are the hardest to reach in a severe humanitarian crisis. But it is expensive, complicated and, as aid workers repeatedly told me, not nearly enough.

There are three road corridors into South Sudan along which aid can travel by truck. And this can be more efficient. One truck alone can carry as much as a Russian transport plane.

Yet trucks have deal with checkpoints, fighting and simple banditry. And soon they will lose the roads when the rains come and render much of the country impassable. So there is, aid workers say, a race against time to build up aid dumps before the weather closes in.

Such is the reality of delivering British and other aid in the north. To the south, in the capital, Juba, the UK is funding much of South Sudan's only children's hospital - its medicines, its water tanks, its solar panels. Here doctors are seeing rising numbers of children with acute malnutrition. And inevitably they need more resources, above all more space.

Children in South Sudan are suffering from acute malnutrition

On the day we visited, in one ward alone, there were 43 children sharing 21 beds. I spoke to Rhoda, a 50-year-old woman who had brought in her granddaughter 10 days previously. Cecilia, only 18 months old, arrived severely malnourished. Her mother had died and Rhoda had no milk to feed her. But, she told me, Cecilia's fever and diarrhoea had abated after a few days of milk and porridge.

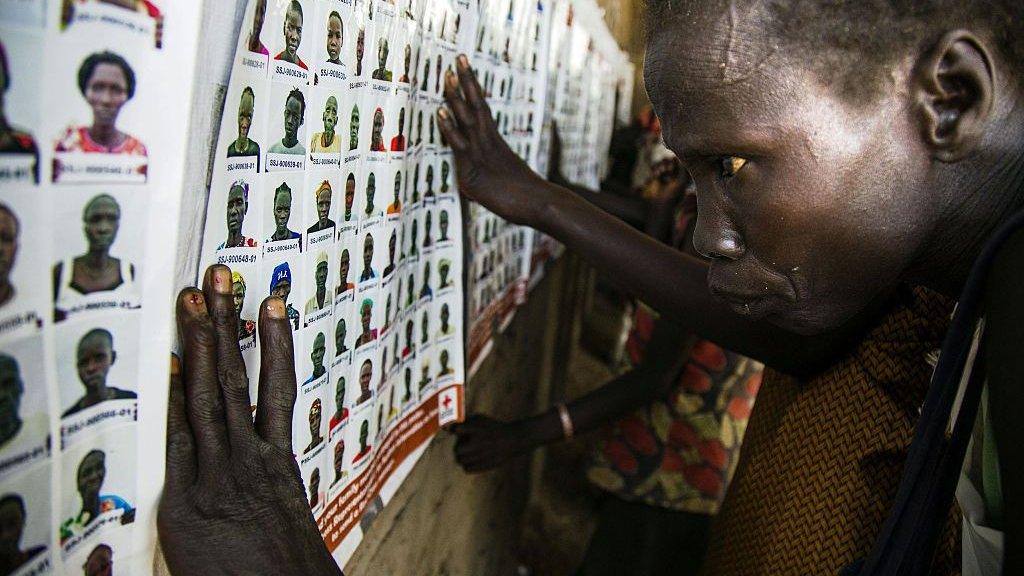

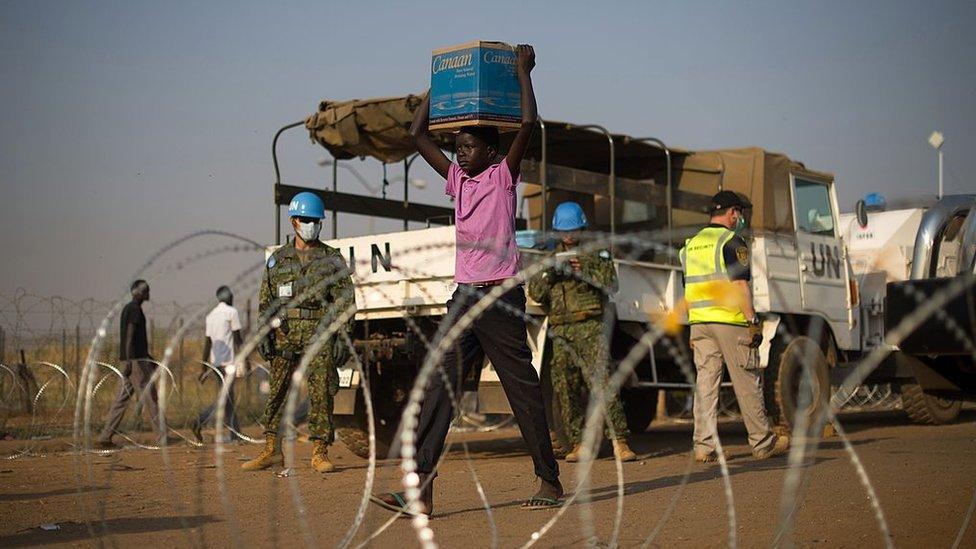

Further south, the problem is one of refugees. More than a million South Sudanese have fled the country to escape the fighting. We travelled to northern Uganda where on average 2,000 people are pouring over the border each day. Last week there was one 24-hour period when no fewer than 7,000 refugees came across.

Bidibidi refugee camp, across the border in Uganda, has quickly grown into the world's largest

Uganda - unusually - welcomes refugees and gives them a plot of land with shelter and access to services. Here millions of pounds of UK aid is being spent to provide some of the basic infrastructure. Yet here again the scale of the crisis outweighs the humanitarian response. Last August there was next to nothing at the main refugee settlement at Bidibidi. Now, it is the largest such settlement in the world, home to more than 270,000 people.

Clearly, the scale of the humanitarian challenge is huge and growing. But the aid agencies report that the United Nation emergency response for South Sudan is hugely underfunded, with some international donors showing reluctance to stump up the cash. So this is a crisis that many expect to get worse before it gets better.

- Published18 April 2023

- Published26 March 2017

- Published20 July 2011

- Published1 December 2016