Letter from Africa: Sudanese fight for their African identity

- Published

The government is seen as trying to suppress an African identity in Sudan

In our series of letters from African journalist, Yousra Elbagir looks at how Sudanese youth are using social media to express their African identity.

Sudan's President Omar al-Bashir has announced a strategic partnership with the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), a regional political organisation that brings together seven Arab states.

The move comes after a series of bilateral talks and a stream of multi-million dollar investments from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

While the East African nation's government leans ever closer to the Arab world - Sudan joined the Arab League two weeks after its independence in 1956 - millennials are taking to social media to celebrate their African heritage.

Skin bleaching

South Sudan's secession in 2011 came after more than 30 years of civil war and a dichotomy of a mainly Arab, Muslim north and a mainly African, Christian south.

The split further polarised those who remained in Sudan, especially those from the Nuba and Darfuri ethnic groups, who are marginalised in the government and in state-backed initiatives to promote a national identity.

President Bashir's focus is on "Arabisation" and establishing Arab supremacy. This is smothering the hundreds of diverse ethnic groups in Sudan, and the country's rich East African heritage.

Yousra Elbagir:

Many southern Sudanese in Khartoum bleach their skins to emulate the northerners they now live amongst.

Popular culture in the capital, Khartoum, is dominated by TV, film and music hailing from Egypt and the Middle East.

Arab celebrities are revered and imitated, sometimes with devastating consequences.

Skin bleaching creams are now an accepted norm, sold at pharmacies and supermarkets throughout Khartoum.

While the phenomenon is prevalent across much of Africa, many southern Sudanese in the city bleach to emulate the northerners they now live amongst. The northerners, in turn, whiten their skins to strengthen their claim to Arab ancestry.

The resultant raw, reddened skin is almost as much a symbol of the push to "Arabisation" as the government's political alliances in the region.

Some photo shoots have tried to show the dominance of Arab culture over African culture

So what has changed to prompt this millennial movement to celebrate afro-centricity and Sudanese pride on social media?

Primarily, it is a space for identity expression that the government cannot control.

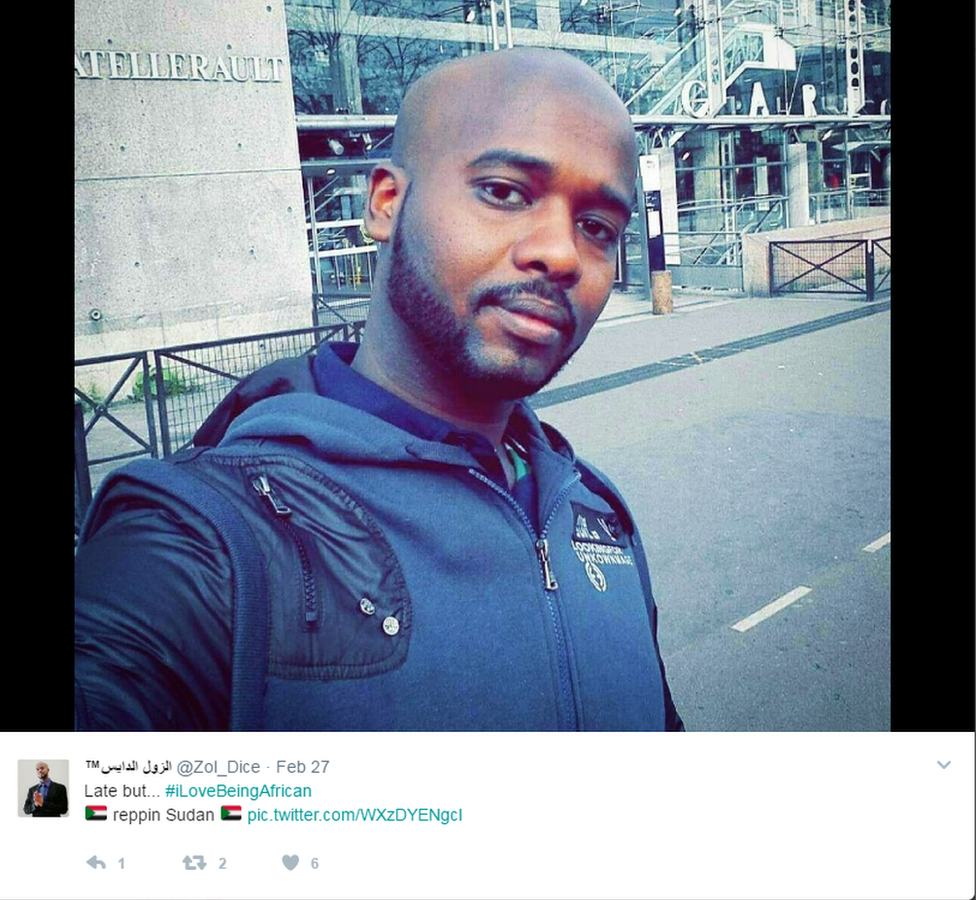

#ILoveBeingAfrican

Jewellery designer Nawar Kamal has made a name for herself by using Instagram to promote and sell her African-inspired beaded pieces.

Photo shoots featuring Sudanese models wearing African prints, and exploring an Afro-Arab identity, are generating excitement across Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.

One shoot in particular, the "Dominance Series" by Enas Satir and Enas Ismail, shows Sudan's "African" face dominated by Arab culture, with a woman in a headscarf and Middle Eastern accessories overshadowing another woman wearing braids, beads and tribal markings.

This new-found - and public - celebration of African identity is not just controversial at home.

When Sudanese tweeters posted photos to the trending topic "#ILoveBeingAfrican", West Africans asked: "What is Sudan and why is it here?"

Sudanese users responded by flooding the hashtag with photos, asserting their right to join the conversation.

Twitter feuds aside, many of Sudan's artists - from painters to poets - are drawing inspiration from this conflicted identity, using artistic mediums to capture customs and traditions that are neither African nor Arab but distinctly Sudanese.

In Sudan, as in much of Africa, social media is home to the elite. The hope, though, is that this message of African pride reaches the far corners of the country.

In the western and southern regions where Darfuri and Nuba ethnic groups use cultural expression as a tool for resistance against a regime that denies them relevance.

Here, age-old traditions are not passing trends but an assertion of identity in the face of disenfranchisement and can often be a matter of life and death.

More from Yousra Elbagir:

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, on Facebook at BBC Africa or on Instagram at bbcafrica