Is Africa facing a new wave of piracy?

- Published

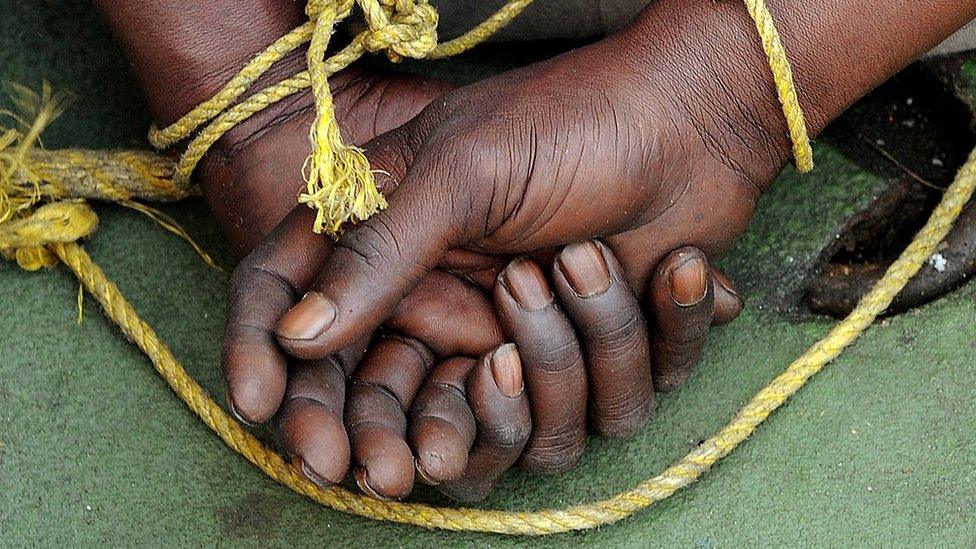

The recent hijacking of a ship by Somali pirates was the first such incident off the Horn of Africa since 2012, and more ships are being targeted off West Africa. But why are attacks increasing and how should the international community respond?

The latest State of Maritime Piracy report, external by the watchdog Oceans Beyond Piracy (OBP) warns against security complacency in the shipping industry, particularly around the Horn of Africa. It appears the industry has gone from a state of heightened security awareness to taking its foot off the pedal.

After five years without any hijackings, the Comoros-flagged vessel Aris 13 was seized in March off the coast of Somalia. Pirates freed the oil tanker and its Sri Lankan crew three days later without ransom. But within weeks, there had been more incidents.

On the other side of the continent, piracy has not declined even though its form has changed. In its 2015 report, the OBP noted that attacks were on the rise off the West African coast.

One out of every five pirate attacks takes place there, making it the most dangerous region for seafarers.

Pirates used to seize oil tankers for their cargo but falling oil prices made this less lucrative, so there was a shift to kidnapping for ransom.

Foreign seafarers were the obvious targets, as the pirates can make higher ransom demands for them. These attacks were also reported to be more violent. That trend appears to have continued. West African governments have poor surveillance systems, which criminals can exploit.

Piracy off Africa reached its heights in 2010-11, prompting a major international response

At its peak - between 2010 and 2011 - piracy off the Horn of Africa cost the shipping industry up to $7bn (£5.42bn) annually. This prompted an international response led by the tripartite coalition of Nato, the European Union Naval Force, external (EU NAVFOR) and the US Combined Maritime Forces.

The use of private security, which was once frowned upon, became common practice.

The associated costs and the overall success must have fed the perception that the piracy had been solved.

In November 2016, Japan scaled down its counter-piracy mission in the Gulf of Aden. Weeks later, Nato ended its operation Ocean Shield, which operated around the same area, hailing it as one of the organisation's most successful ever missions, one which had achieved its objectives.

However, the pirates never really went away. They just could not strike because of the armed presence in their seas.

It's a point that the former Operation Commander for EU NAVFOR Maj Gen Martin Smith explained to me more than a year ago.

"We've taken away the opportunity for pirates to go to sea… but we're very conscious that the capability required is fairly basic," he said.

Though subdued, the pirate networks still exist, warns Maj Gen Martin Smith

"Secondly we are aware that the intent still exists. The pirate networks still exist, they're just doing other things and we believe that if we gave them back the opportunity they would go back to piracy."

Now it appears that that is exactly what has happened, as some of the anti-piracy units have completed their mission and have headed home.

This is coupled with the issue of illegal fishing by foreign vessels in the area.

One of the pirates who hijacked the Aris 13 told the BBC Somali Service that the foreign ships are not just depleting fish reserves but are also attacking local fishing boats.

"We were after a particular ship that destroyed some of our equipment, when we came across this one, about eight miles from the coast," he claimed. "It came across initially as a fishing vessel, and later on, when we went inside, we discovered that it [was] a cargo ship, transporting oil. We had to hold it, because we have nothing to lose anyway."

While these claims cannot be independently verified, it is true that vessels from elsewhere in the world come to fish illegally in the waters off the Horn of Africa.

EU NAVFOR Somalia patrols the country's coast and its territorial and internal waters

The Stop Illegal Fishing campaign highlights a global enforcement imbalance as one of the key reasons for the trend.

As it says: "Effective controls in other regions force illegal operators to seek alternative fishing areas where the risk of being caught is lower and the sanctions if caught are less severe, such as the [Western Indian Ocean]."

The mandates of the international naval patrols are limited to counter-piracy operations, rather than maritime policing.

The problems both on the eastern and western coasts of Africa involve the absence, or poor implementation, of regional maritime strategies. Ninety per cent of Africa's imports and exports are conducted by sea.

Its waters also include key global shipping lanes, such as the Gulf of Aden, so securing these channels would be of great value to the continent and its partners, who both need to show the will to see maritime security improved.

- Published13 November 2014

- Published31 August 2015