'I thought I was going to die': Jailed and ransomed in Libya

- Published

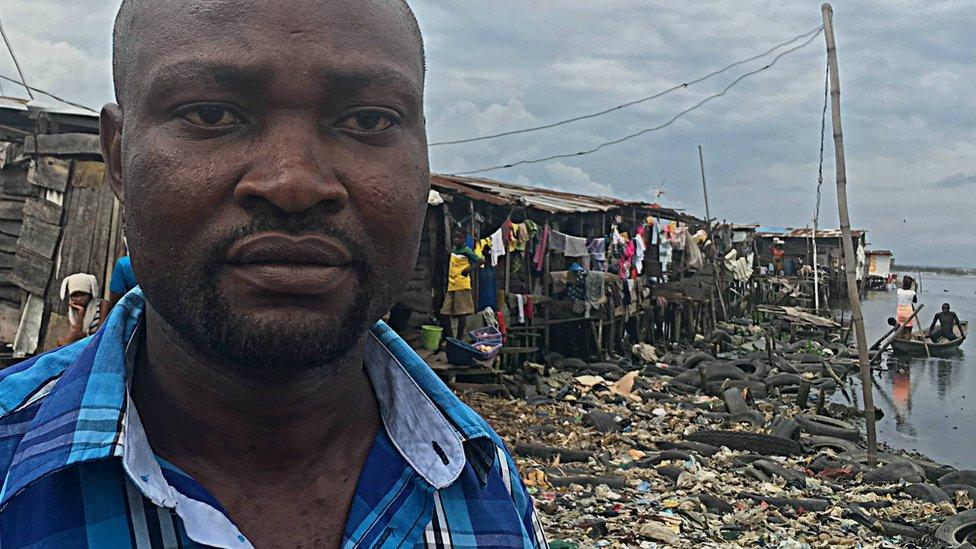

Back home in Nigeria, Seun says he regrets ever setting out for Europe

It was called "Morning Tea" - a brutal flogging with a hosepipe.

Every morning for four months, Seun Femi's captors beat him at a makeshift prison in Libya.

"They would flog my head, my hands, my bum," says the 34-year-old. "The guard would beat me until he got tired."

Two of Seun's fingers were broken during one of the brutal sessions. But the Nigerian says it could have been far worse. One man was beaten to death in front of him.

"I thought I was going to die in that prison," he says.

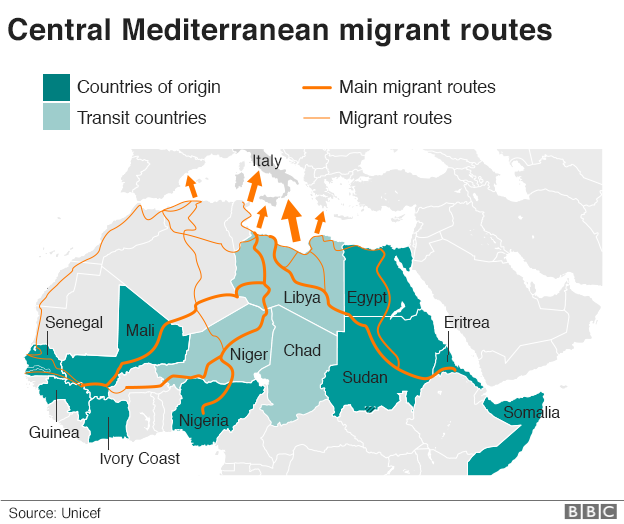

Seun was one of the tens of thousands of West Africans who cross the Sahara Desert into Libya every year, from where they hope to be trafficked by boat to Europe.

Desperate journey

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) estimates there are between 700,000 and one million people in Libya awaiting their chance to cross the Mediterranean.

It was always a dark and desperate journey but now appears to be increasingly dangerous as undocumented migrants fall prey to militias and criminal gangs in war-torn Libya.

Earlier this year, the IOM reported that African migrants were being sold by their captors in "slave markets" in the south-western Libyan city of Sabha.

It was in the same city that Seun says he was held with about 300 other African migrants for ransom.

"We thought the traffickers were taking us to a place to stay and not a place to lock us up," he says.

Seun says a hunchbacked Libyan called Ali ran the makeshift prison.

Read more:

It was a half-constructed building. The male migrants, mainly from Nigeria, Ghana and Senegal, were separated into large rooms, each called a ghetto. Seun was held in the Nigeria ghetto.

In two of the ghettos, called Ghana and VIP (for very important person), the guards would extort a higher ransom in order for the migrants to be freed.

"We were packed on the floor like sardines when we tried to sleep," says Seun.

There was little food but enough bottled water as otherwise the migrants would die of thirst in the stifling heat.

Up to one million migrants are thought to be in Libya attempting to reach Europe

The brutal business model was simple, says Seun. Guards with nicknames like "Rambo" would beat the migrants and then hand them a phone.

"They would let us phone our people once a day," he said. "They would whip us while we were on the call so our families would get the message. We would beg them to send us money."

On Tuesday, the Italian authorities said they had arrested a notorious human trafficker known as Rambo on charges of torturing and killing migrants but it is not possible to verify whether it was the same man.

'He helped me'

Seun needed to a pay a ransom of approximately $500. It was to be deposited in a bank account in Nigeria. But he did not have the money. He urged his ex-girlfriend to sell his car.

"It was in bad shape. It took three months for her to sell it," says Seun. "There were no buyers."

The irony is that Seun, a taxi driver, had no money to repair the vehicle in the first place, which is why he decided to go to Libya.

How I smuggle people from Nigeria to Europe

His ransom was finally paid last December. Seun thought he was free.

But then he was told he needed to pay a "gate-fee" of approximately $50. He had no money. But a Nigerian baker who sold bread at the prison took pity on him and paid the fee.

"He helped me a lot by taking me out of that place - it's bad, very bad," says Seun.

Seun then paid the man back by working in his bakery for several weeks in Sabha.

He then pushed on to Tripoli but was detained by Libyan police earlier this year and held at a detention centre. He was repatriated to Nigeria in April.

Now back in Lagos, he has no work, and rents a small dark room in one of the city's sprawling slums. He is trying to piece his life back together.

He hopes to raise cash to buy a car and work as a taxi driver again. He wants to move to a better area so his young daughter can visit. He regrets ever setting out to Europe.

"The desert is such a dangerous place," he says. "Many people died on the way. No-one should follow that path."

- Published11 April 2017

- Published28 April 2017

- Published30 March 2016

- Published23 January 2020

- Published8 May 2017