Bringing African folktales to life

- Published

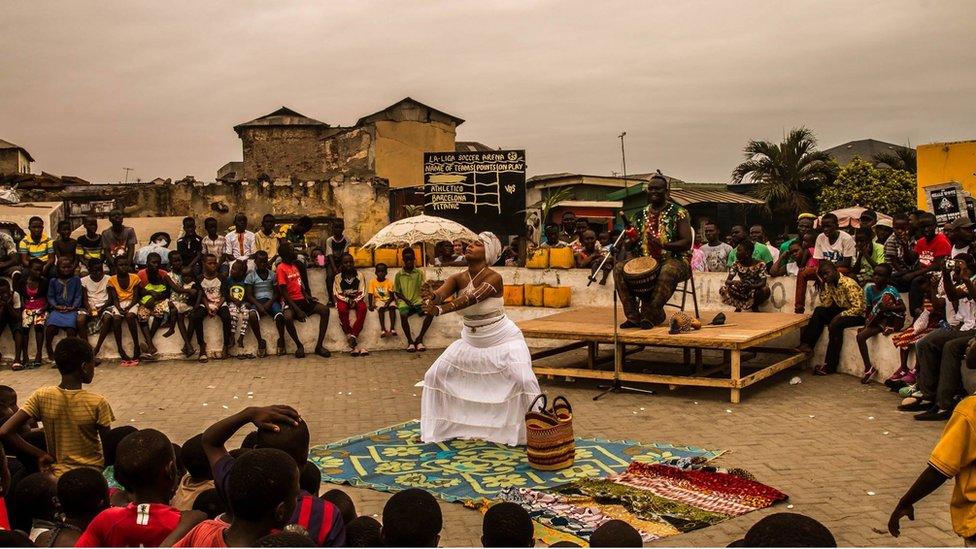

Maimouna is trying to get audiences interested in folktales again

Folktales and the art of traditional storytelling are in danger of being lost and Nairobi-based performer Maïmouna Jallow is on a mission to reverse the trend. But on her journey to revive the art she has also discovered the relevance of performing contemporary stories.

There is something mystical about Zanzibar's Stone Town. It is a place where past and present collide, and where a mosaic of sights and smells from across the Indian Ocean weave themselves together down narrow alleyways.

It is perhaps fitting then, that my exploration of traditional East African folktales began here, leading me on an unexpected journey into storytelling and adapting contemporary novels.

In 2015, feeling nostalgic for the tales of Anansi the Spider that I had grown up with in West Africa, I travelled to the historic centre of Zanzibar in search of folktales.

Stone Town's narrow streets and old buildings proved the perfect setting to rediscover old folktales

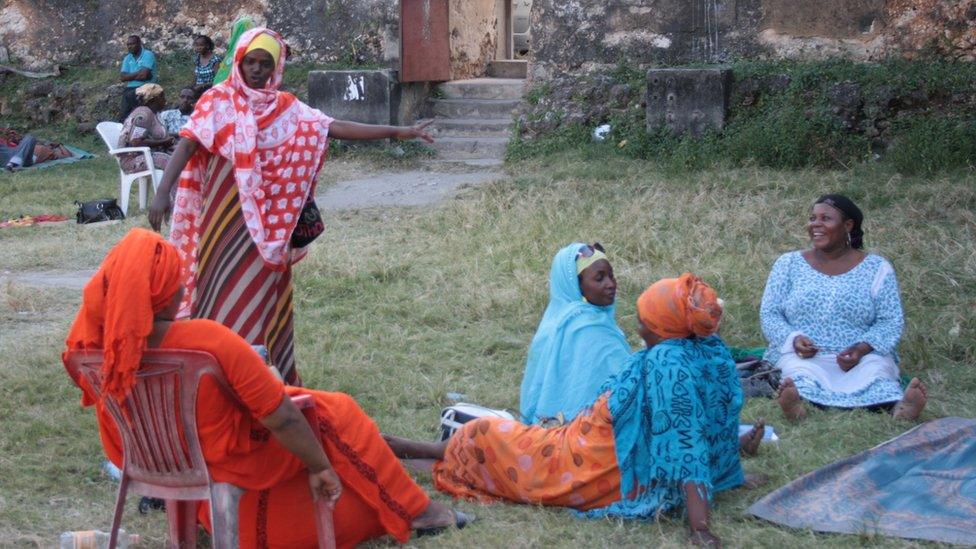

On arrival, I went straight to the Old Fort, an imposing 17th Century structure built by the Omanis to defend the island from the Portuguese. There, with the help of the painter Hamza Aussie, I met a group of women who owned curio shops that lined the grassy courtyard.

I asked them if they would share the folktales of their youth with me, and within a couple of hours, I had recorded a dozen stories, or rather, fragments of stories.

Around us, children pressed inwards, eager to hear their tales. But even in those magical hours, I started to feel like I was grasping at clouds. The women had to dig deep into the recess of their minds as they tried to piece together scattered bits of ancient tales.

Like an old discarded puzzle, some pieces seemed to be lost forever.

Maimouna heard traditional stories from women in Zanzibar

The children around us, whilst enchanted by their tales, would save their coins to play computer games in the gaming rooms that had sprouted alongside shops that sold henna and incense.

It seemed that even in this small town, famed for its quaint antiquity, folktales were dying. I needed to understand why.

Yes, television was to blame, and so was the breakdown of the extended family, but how had we so easily lost such a fundamental kernel of our existence?

Later that week, I had the good fortune of meeting Haji Gora Haji, the Island's poet laureate, a living fountain of wondrous tales.

As I listened to him recount a story about the infamous Hare duping Tortoise into buying a piece of land that turned out to be a beach, which Tortoise only found out about when the tide came in, I wondered whether part of the problem is that so many of these stories are far removed from our realities today.

Would our urbanised kids understand Haji's story?

Heck, even I needed Hamza to give me the annotated version. As he explained it, there was a time when many people on the island were being conned into buying land without title deeds, so this was a warning to people to be wary of unscrupulous salesmen.

Indeed, folktales have always been a vital way to transmit important information, as well as moral lessons, and as such, they are often rooted in specific places and contexts.

And as much as the purist in me wanted to believe that folktales are not only timeless but also universal, I started to think that perhaps one way to preserve folktales was to re-imagine them so that they would resonate with children and adults today.

Back in Nairobi, I launched an online contest, inviting African writers to re-write traditional folktales but with a contemporary twist.

We got a mixed bag of entries, some which addressed war and exile, others that questioned our modern mores. I too began writing stories that merged the old with the new, for example, drawing parallels between slavery and the indiscriminate killing of young black men in America.

I began performing these stories, at times using video footage of real events to ground them in reality, but preserving the structure and style of traditional folktales. The result was as hybrid as me, and whilst I worried about veering off track, I knew that are so many of us who inhabit multiple worlds.

The success of this experiment spurred me to push the boundaries even further and to use oral storytelling to bring African literature to new audiences by adapting novels for performance. I have author Lola Shoneyin thank for this.

The first time I read her acclaimed novel, The Secret Lives of Baba Segi's Wives, the women in the story possessed me. They were hilarious. And they jostled for space in my mind, speaking loudly, and demanding to be seen.

My initial reaction was to think, "someone needs to turn this into a movie". But soon, I realised that I wanted to tell this story.

One-woman show

It was about patriarchy, sexual abuse, polygamy, poverty, education, love, friendship and so many issues that I wanted to talk about, and I felt that performance storytelling could be a gateway to have open discussions on the serious questions raised by the novel.

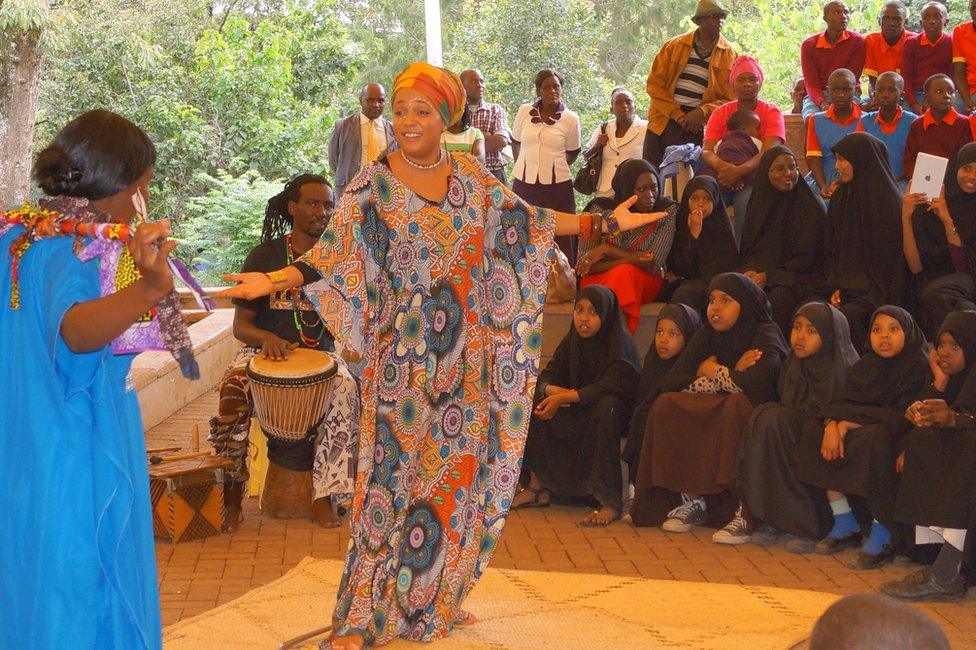

So I set about adapting the book into a 50-minute one-woman show.

Then, I dug into my bookshelves and pulled out other novels that I thought would translate beautifully into performed stories. I worked with five other women, an eclectic mix of poets, actors and writers, and together we started to bring African novels to life.

These were not plays. Each novel was adapted and retold by just one teller. We used traditional elements of African oral storytelling like call and response and each time, the teller would build a relationship with the audience and create a different form of magic.

The response was tremendous. Audiences told us that we had brought books to life. Some said they did not read and were grateful to still be able to enjoy the terrific literature coming out of Africa.

Many subsequently bought the novels so that they could enjoy the full details that had to be left out in the adaptations.

As an African literature major, it dawned on me that my journey had come full circle: folktales had led me back to contemporary novels and opened the door to storytelling. So perhaps I have not veered off track after all.

The late Professor Kofi Awoonor used to say: "We weave new ropes where the old ones left off." And like Stone Town itself, I have simply found a way to fuse past and present.

Maïmouna Jallow performed The Secret Lives of Baba Segi's Wives at the Africa Writes Festival, external in London on Saturday 1 July