Has voodoo been misjudged?

- Published

The Temple of Pythons in Benin is considered a sacred place by voodoo followers

While many African traditions and cultures are under threat from modern life, there is one which is holding its own - voodoo.

It has suffered from a bad press internationally but is an official religion in the West African country of Benin.

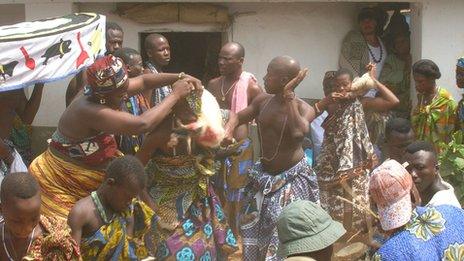

In the voodoo heartland of Ouidah, the sound of drums fills the air, while men and women dressed mainly in white take turns to dance around a bowl of millet, a freshly slaughtered chicken and alcohol.

These are the day's offering at the Temple of Pythons.

They have an audience of about 60 people who have gathered from nearby towns for an annual cleansing ceremony.

Inside the temple, where more than 50 snakes are slithering around a custom-made pit, local devotees make amends for sins of the past year.

Blood, snakes and power

In voodoo, the python is a symbol of strength - the devotees explain they are relying on Dagbe, the spirit whose temple this is, to give them the power to change.

And to make that change happen, blood must be spilled.

Animal sacrifices are an important part of voodoo ceremonies - an offering to appease the spirits

The first offering is a chicken - some of the blood is spread across the tiles of the temple and the rest is mixed into a communal bowl of millet - which the devotees eat as it is passed around.

Voodoo is rooted in the worship of nature and ancestors - and the belief that the living and the dead exist side by side - a dual world that can be accessed through various deities.

Its followers believe in striving to live in peace and to always do good - that bad intentions will not go unpunished, a similar concept to Christians striving for "righteousness" and not "sinning".

Voodoo believers communicate with their gods through prayers and meditation

Modest estimates put voodoo followers here at at least 40% of Benin's population. Some 27% classify themselves as Christians and 22% Muslims.

But expert on African religions and traditions Dodji Amouzouvi, a professor of sociology and anthropology, says many people practice "dual religion".

"There is a popular saying here: 'Christian during the day and voodoo at night'. It simply means that even those who follow other faiths always return to voodoo in some way," he tells me.

To illustrate the closeness of the two faiths, there is a Basilica opposite the Temple of Pythons in the town square.

"At the moment many people here in Benin feel let down by the establishment, there are no jobs," Mr Amouzouvi.

"People are turning to voodoo to pray for better times."

But how did voodoo get exported to places such as New Orleans and Haiti?

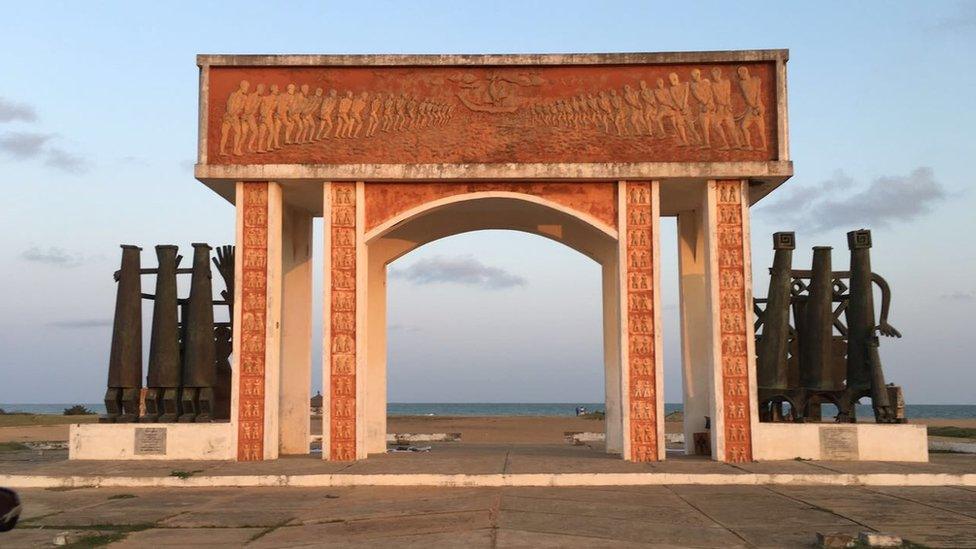

At the edge of the sea in Ouidah stands La Porte du Non-Retour "The Door of No Return" - a stone arch monument with carvings of men and women in chains walking in a procession towards a ship.

The Door of No Return is a reminder of Benin's painful slave history

It was from this point that many thousands of African slaves were packed into ships and taken to the Americas - the only thing they took with them was voodoo, which they clung to as a reminder of home.

They continued to practise it, at times being beaten if caught by the slave masters.

This made some even more determined to keep it alive, according to reports.

Some practices in voodoo can appear threatening to the outsider - the slaughtering of animals have in part earned the faith its unflattering image, some say.

But Mr Amouzouvi says voodoo is not all that different to other faiths.

"Many religions recognise blood as a source of power, a sign of life. In Christianity it's taught that there is power in the blood of Jesus," he says.

"Voodoo teaches that there is power in blood, it can appease gods, give thanks. Animals are seen as an important part of the voodoo practice."

Regine Romaine, an academic with a keen interest in voodoo, agrees.

"The African experience is open for all to see - people are invited to witness the ceremonies, the slaughtering and that same openness has been judged whereas it isn't in other systems like the Islamic and Jewish faiths," she tells me.

"Slaughtering animals is not unique to voodoo. If you go to the kosher deli or buy halaal meat, it's been killed and allowed to bleed out before being shared.

"Ultimately, the gaze on voodoo over the years has not been one of love - that's why it's been given a bad image."

Ms Romaine is of Haitian and US heritage.

She first learned about voodoo from her aunt in Haiti - she travelled on a pilgrimage to retrace the "slave route" and her last stop was here in Benin where she has been living for more than a year.

'Voodoo is not evil'

According to Ms Romaine, voodoo's bad image abroad has a lot to do with what people have seen in Hollywood films.

"The image of voodoo went wrong from the first encounter - from the first visitors to the continent, the anthropologists who didn't understand what they were seeing and from that came a lot of xenophobic writing," she says.

"It was also worsened by the US invasion of Haiti much later, which gave rise to Hollywood's fascination with the horror stories that all had voodoo."

Back at the ceremony, the processing of devotees has now moved to the town square for the final stage of the rituals.

There is more drumming, singing, dancing and after four animals are killed and cooked inside three large flaming pots of clay, the meat inside is shared by all those who have attended the day's proceedings.

The Regional High Priest of Voodoo Daagbo Hounon is presiding over the day's rituals.

He is dressed in ceremonial robes, with a striking top hat, and holding a staff made from cowry shells.

Regional High Priest of Voodoo Daagbo Hounon says voodoo has been unfairly judged by outsiders over the years

He is a big man with a booming voice and speaks passionately about their belief system - he tells me that their faith is misunderstood.

"Voodoo is not evil. It's not the devil," he says.

"If you believe and someone thinks badly of you and tries to harm to you, voodoo will protect you. Some say it is the devil, we don't believe in the devil and even if he exists, he's not here," he tells me.

He is keen to welcome international visitors.

The small town offers an "initiation" from people from all over the world to come and learn about the practice - from how to use herbal medication, how to pray and meditate, how to perform rituals for the gods.

High Priest Hounon says the programme is popular with tourists from the US, Cuba and parts of Europe.

For many West Africans in the diaspora, voodoo has become a symbolic coming home.

Ceremonies are a chance for young and old to come together and celebrate

Ms Romaine, who is also member of that diaspora, believes voodoo is successful because it provides a connection to a neglected identity.

She tells me that voodoo is gaining appeal in the US amongst young people.

"There is a shift especially in the Americas. The younger generation now want to proclaim their identity in a way that the previous generation was perhaps more intimidated to do and spiritual identity is a part of that. For some voodoo meets that need."

The government here in Benin is committed to upholding the practice.

In the mid 1990s it built a monument to voodoo in a place known as the sacred forest - an ancient place of worship on the edge of town.

Life-sized metal and wooden totems have pride of place amongst the towering trees - this place is meant to help teach young people here about their voodoo heritage.

With the government supporting it at home and the descendants of slaves embracing it abroad, the ancient voodoo tradition has found a place in the modern world, where other African belief systems are often struggling for relevance.

Read more from Pumza on Africa's disappearing cultures:

- Published30 January 2017

- Published18 November 2011

- Published29 November 2012

- Published19 November 2011