Boko Haram and al-Shabab recruits 'lack religious schooling'

- Published

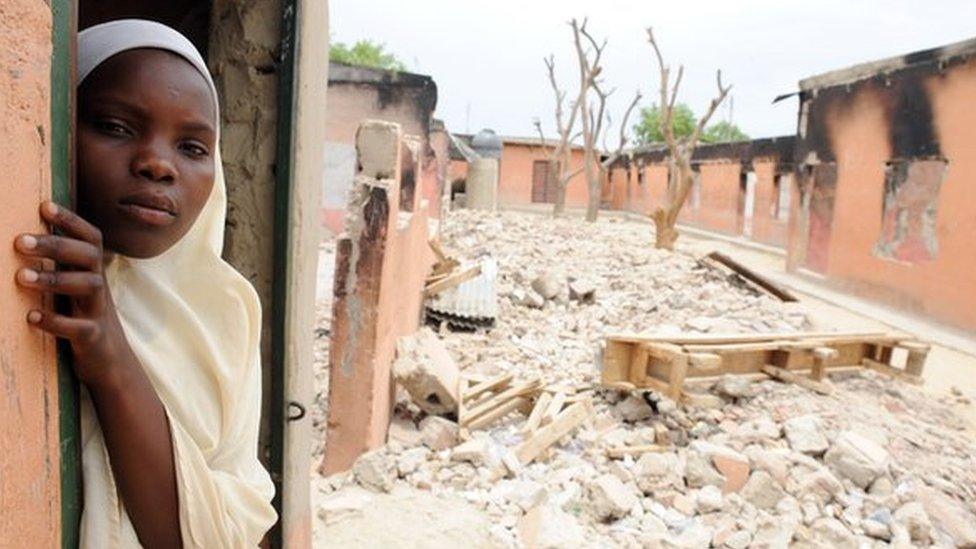

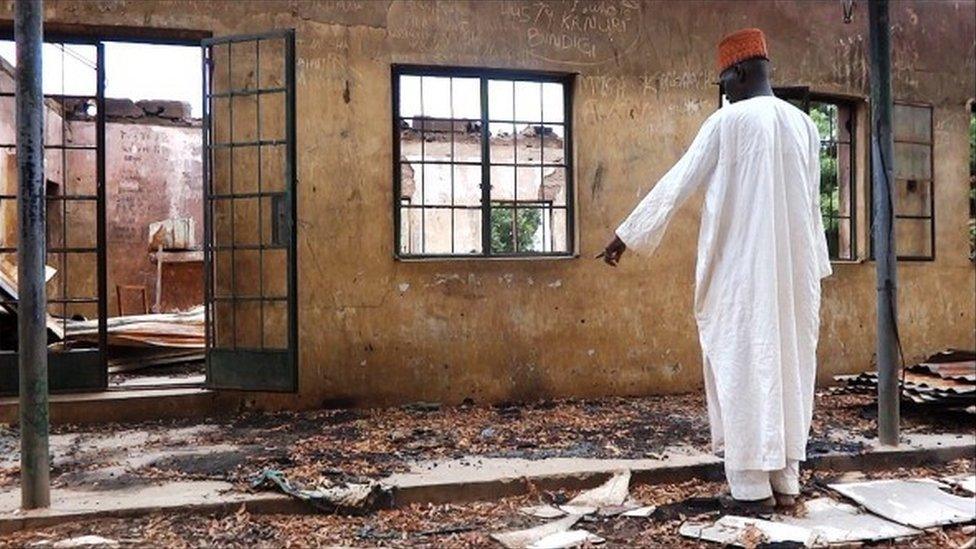

Boko Haram, whose name means "Western education is forbidden", has often attacked schools in northern Nigeria

Many young Africans drawn to extremist groups know "little to nothing" about religious texts and interpretations, a UN study has found.

The survey, the first of its kind in Africa, profiled nearly 500 voluntary recruits to militant groups including al-Shabab and Boko Haram.

Finding a job is "the most acute need at the time of joining a group," the report finds.

It also points to government action as a "tipping point".

Most of those surveyed reported unhappy childhoods and a lack of parental supervision.

Researchers from the UN Development Programme (UNDP) spoke to recruits in Kenya, Nigeria, Somalia, Sudan, Cameroon and Niger to compile the report.

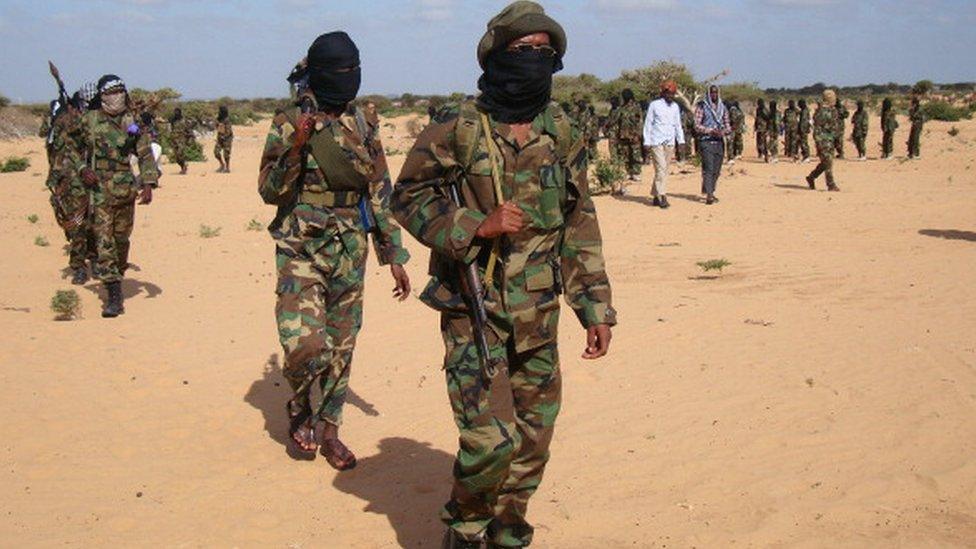

Al-Shabab is based in Somalia but often stages attacks in Kenya, while Nigeria's Boko Haram group has also spread to neighbouring Niger and Cameroon.

The researchers also interviewed people of similar backgrounds to those recruited, but who did not become radicalised.

Based on these sample groups, they say that receiving "at least six years of religious schooling [is] shown to reduce the likelihood of joining an extremist group by as much as 32%".

The UN estimates that 33,300 people in Africa have lost their lives to violent extremist attacks between 2011 and early 2016

Recruitment is "predominantly face-to-face" rather than online as outside Africa, and the report says that many recruits come from borderland areas that have "suffered generations of marginalisation".

The killing or arrest of a family member or friend is a key trigger, according to the report, with over 70% of interviewees saying this or another form of government action was the "tipping point" before the final decision to join a militant group.

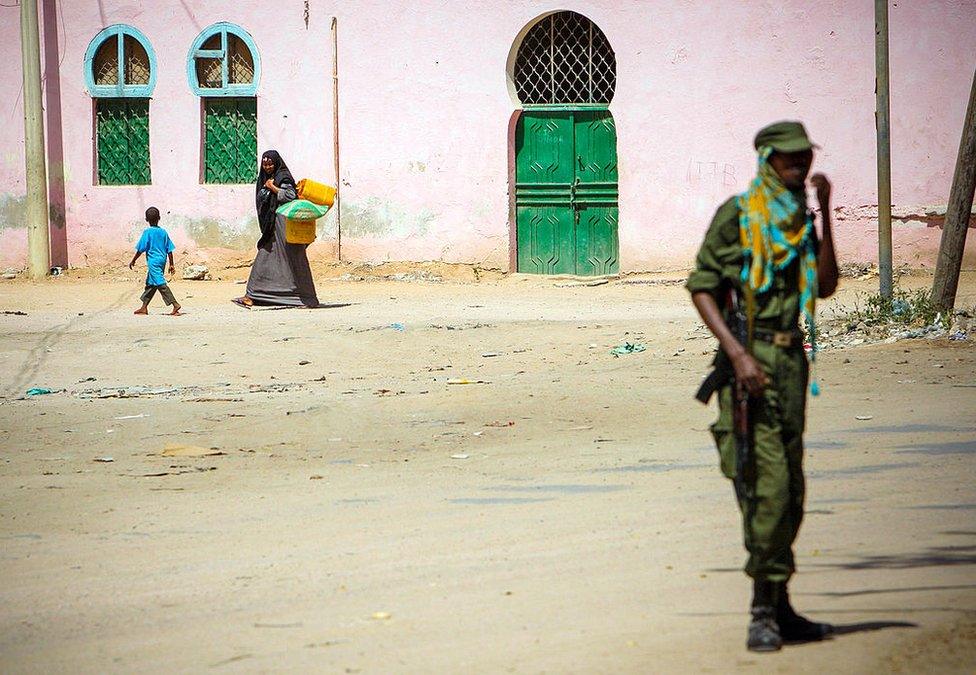

A solider in Somalia stands guard while engineers search the area for explosives planted by al-Shabab

Intervention at a local level is the best way to prevent young people from being radicalised, the UNDP report authors say.

They suggest "community-led initiatives aimed at social cohesion" and "amplifying the voices of local religious leaders who advocate tolerance".

"The messenger... is as important as the message," says UNDP Africa Director Abdoulaye Mar Dieye.

"That trusted local voice is also essential to reducing the sense of marginalisation that can increase vulnerability to recruitment," he adds.

- Published22 March 2016

- Published25 May 2017

- Published22 December 2017

- Published24 November 2016