Emmerson Mnangagwa: The 'crocodile' who snapped back

- Published

Emmerson Dambudzo Mnangagwa, the man known as "the crocodile" because of his political cunning, achieved a long-held ambition to succeed Robert Mugabe as Zimbabwe's president in November last year.

He has now won a disputed presidential election to legitimise his rule, promising voters his efforts to woo foreign investors will bring back the economy from the brink of collapse.

Mr Mugabe resigned following a military takeover and mass demonstrations - all sparked by his sacking of Mr Mnangagwa as his vice-president.

"The crocodile", who lived up to his name and snapped back, may have unseated Zimbabwe's only ruler, but he is also associated with some of the worst atrocities committed under the ruling Zanu-PF party since independence in 1980.

One veteran of the liberation struggle, who worked with him for many years, once put it simply: "He's a very cruel man, very cruel."

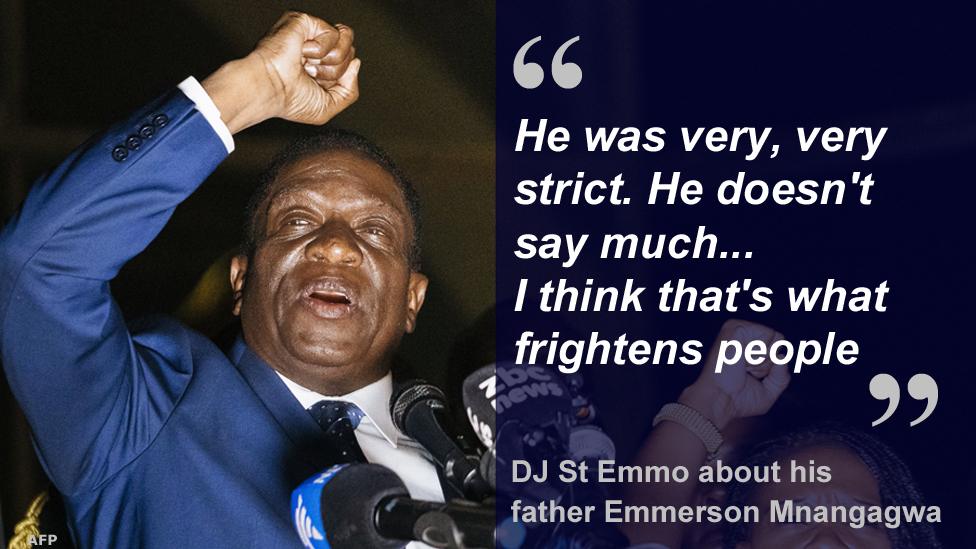

But his children see him as a principled, if unemotional, man. His daughter, Farai Mlotshwa - a property developer and the eldest of his nine children by two wives - told BBC Radio 4 that he was a "softie".

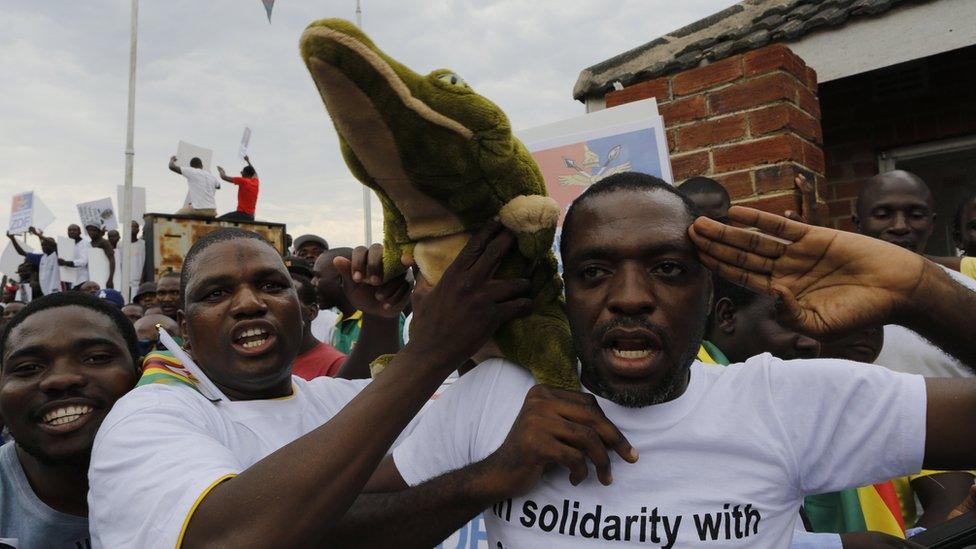

As if to reinforce this softer image of the new leader, a cuddly crocodile soft toy was passed among the Zanu-PF supporters who welcomed him back to the country after Mr Mugabe's resignation.

Emmerson Mnangagwa is known as "Ngwena", the Shona word for crocodile

And what he lacks in charisma and oratory prowess, he makes up for in pragmatism, says close friend and Zanu-PF politician Josiah Hungwe.

"Mnangagwa is a practical person. He is a person who recognises that politics is politics but people must eat," he told the BBC, adding that reforming Zimbabwe's disastrous economy will be the focus of his leadership.

Who is Emmerson Mnangagwa?

Emmerson Mnangagwa: Who is the man known as the ‘crocodile’?

Known as "the crocodile" because of his political shrewdness - his Zanu-PF faction is "Lacoste"

Received military training in China and Egypt

Tortured by Rhodesian forces after his "crocodile gang" staged attacks

Helped direct Zimbabwe's war of independence in the 1960s and 1970s

Became the country's spymaster during the 1980s civil conflict, in which thousands of civilians were killed, but has denied any role in the massacres

Accused of masterminding attacks on opposition supporters after 2008 election

Says he will deliver jobs, and seen as open to economic reforms

Survived several alleged assassination attempts, blamed on Mugabe supporters

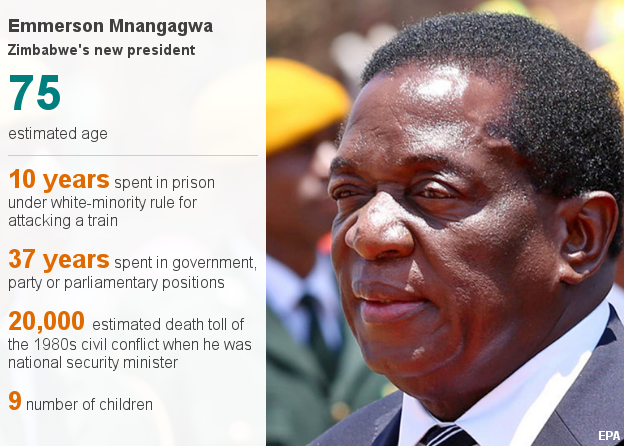

The exact year of Mr Mnangagwa's birth is not known - but he is thought to be 75, which would make him nearly 20 years younger than his predecessor who left power aged 93.

Born in the central region of Zvishavane, he is a Karanga - the largest clan of Zimbabwe's majority Shona community.

Some Karangas felt it was their turn for power, following 37 years of domination by Mr Mugabe's Zezuru clan, though Mr Mnangagwa was accused of profiting while under Mr Mugabe.

According to a United Nations report in 2001, he was seen as "the architect of the commercial activities of Zanu-PF".

This largely related to the operations of the Zimbabwean army and businessmen in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Zimbabwean troops intervened in the DR Congo conflict on the side of the government and, like those of other countries, were accused of using the conflict to loot some of its rich natural resources such as diamonds, gold and other minerals.

More recently military officials - many behind his rise to power - have been accused of benefiting from the rich Marange diamond fields in eastern Zimbabwe, with reports of killings and human rights abuses there.

'Blood on his hands'

Despite his money-raising role, Mr Mnangagwa, a lawyer who grew up in Zambia, was not always well-loved by the rank and file of his own party.

A Zanu-PF official posed an interesting question when asked about Mr Mnangagwa's prospects: "You think Mugabe is bad, but have you thought that whoever comes after him could be even worse?"

The opposition candidate who defeated Mr Mnangagwa in the 2000 parliamentary campaign in Kwekwe Central, Blessing Chebundo, might agree.

During a bitter campaign, Mr Chebundo escaped death by a whisker when the Zanu-PF youths who had abducted him and doused him with petrol were unable to light a match.

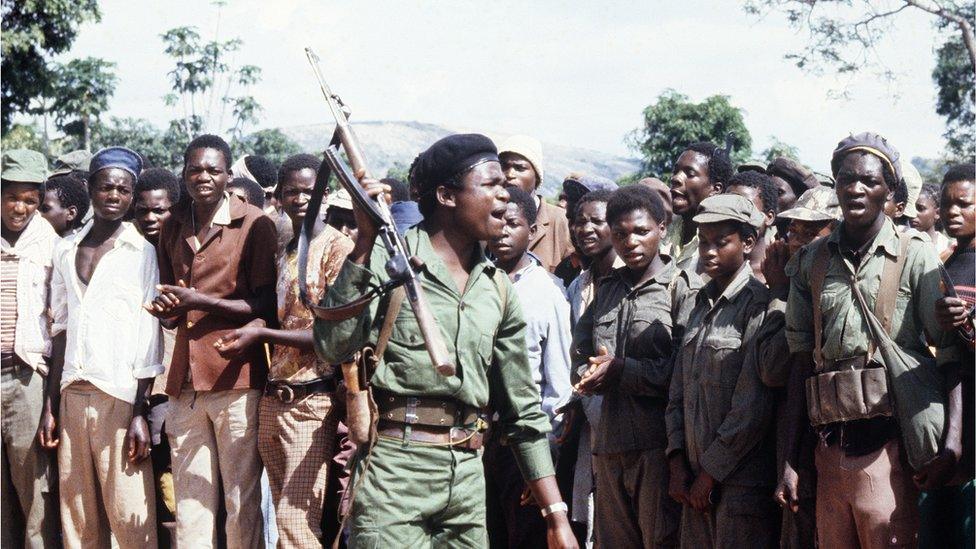

Those who fought in Zimbabwe's war of independence have long monopolised power

Mr Mnangagwa's fearsome reputation was made during the civil war which broke out in the 1980s between Mr Mugabe's Zanu party and the Zapu party of Joshua Nkomo.

As national security minister, he was in charge of the Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO), which worked hand in glove with the army to suppress Zapu.

Thousands of civilians - mainly ethnic Ndebeles, seen as Zapu supporters - were killed in a campaign known as Gukurahundi, before the two parties merged to form Zanu-PF.

Among countless other atrocities carried out by the North Korean-trained Fifth Brigade of the army, villagers were forced at gunpoint to dance on the freshly dug graves of their relatives and chant pro-Mugabe slogans.

Mr Mnangagwa has denied any role in the massacres, but the wounds are still painful and many party officials, not to mention voters, in Matabeleland might find it hard to back Mr Mnangagwa.

He does enjoy the support of many of the war veterans who led the campaign of violence against the white farmers and the opposition from 2000.

They remember him as one of the men who, following his military training in China and Egypt, directed the fight for independence in the 1960s and 1970s.

He also attended the Beijing School of Ideology, run by the Chinese Communist Party.

'Torture scars'

Mr Mnangagwa's official profile says he was the victim of state violence after being arrested by the white-minority government in the former Rhodesia in 1965, when the "crocodile gang" he led helped blow up a train near Fort Victoria (now Masvingo).

"He was tortured, severely resulting in him losing his sense of hearing in one ear," the profile says.

"Part of the torture techniques involved being hanged with his feet on the ceiling and the head down. The severity of the torture made him unconscious for days."

As he said he was under 21 at the time, he was not executed but instead sentenced to 10 years in prison.

"He has scars from that period. He was young and brave," a close friend of Mr Mnangagwa once said, asking not to be named.

"Perhaps that explains why he is indifferent. Horrible things happened to him when he was young."

More on post-Mugabe Zimbabwe:

His ruthlessness, which it could be argued he learnt from his Rhodesian torturers, is said to have been seen again in 2008 when he reportedly masterminded Zanu-PF's response to Mr Mugabe losing the first round of the president election to long-time rival Morgan Tsvangirai.

The military and state security organisations unleashed a campaign of violence against opposition supporters, leaving hundreds dead and forcing thousands from their homes.

Mr Tsvangirai then pulled out of the second round and Mr Mugabe was re-elected.

Mr Mnangagwa has not commented on allegations he was involved in planning the violence, but an insider in the party's security department later confirmed that he was the political link between the army, intelligence and Zanu-PF.

Ice cream plot

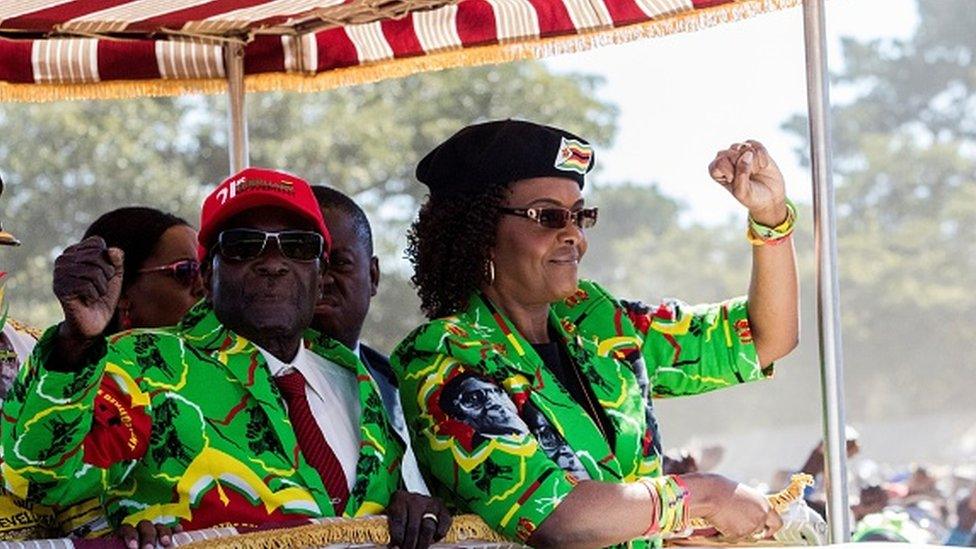

He was seen as Mr Mugabe's right-hand man - that is until the former first lady Grace Mugabe became politically ambitious and tried to edge him out.

Their rivalry took a bizarre turn when he fell ill in August 2017 at a political rally led by former President Mugabe and had to be airlifted to South Africa.

Grace Mugabe (right) bit off more than she could chew by taking on Mr Mnangagwa

His supporters suggested that a rival group within Zanu-PF had poisoned him and appeared to blame ice cream from Mrs Mugabe's dairy firm.

In his first words to cheering supporters after Mr Mugabe's resignation, he spoke about this plot and another plan to "eliminate" him.

He has also blamed a group linked to the former first lady for an explosion in June at a Zanu-PF rally in Bulawayo in which two people died.

But in a BBC interview, he said the country was safe, told foreign investors not to worry and sought to dispel his ruthless reputation: "I am as soft as wool. I am a very soft person in life."

Mnangagwa: Criminal will be hounded down, but Zimbabwe is safe

His youngest son, a Harare DJ known as St Emmo, blames his reticence for his fearsome reputation.

"He was a good father, very very strict. He doesn't say much and I think that's what frightens people - like: 'What is he thinking?'"

Nick Mangwana, Zanu-PF representative in the UK, accepts that the Zimbabwe's new leader is "not the most eloquent".

"He's not pally-pally but more of a do-er, more of a technocrat."

But in his six months in power he has fully embraced Twitter and Facebook - after the Bulawayo blast he posted a message reiterating the strength his Christian faith gives him.

Allow Facebook content?

This article contains content provided by Facebook. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Meta’s Facebook cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

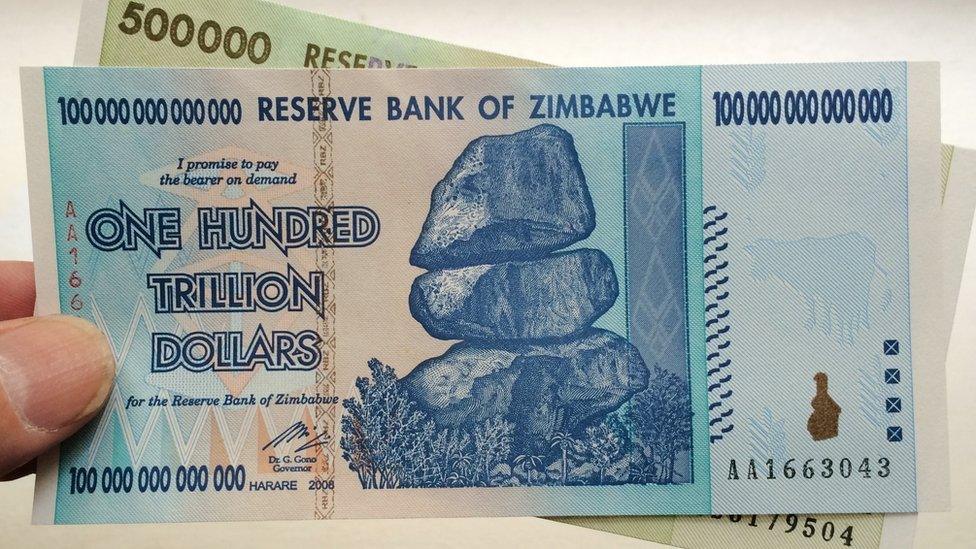

Fixing the economy is what is paramount now. Zimbabweans are on average 15% poorer now than they were in the 1980s.

British journalist Martin Fletcher, who interviewed Mr Mnangagwa in 2016, does not see him a reborn democrat.

"He understands the need to rebuild the economy if only so that he can pay his security forces - and his survival depends on their loyalty," he said.

- Published21 June 2018

- Published25 July 2018

- Published21 November 2017

- Published21 November 2017