Surviving Congo's massacres: 'I climbed over bodies to flee'

- Published

About 1.4 million people have fled the violence

The BBC's Africa editor Fergal Keane travels to the Democratic Republic of Congo's central Kasai region, a land littered with tears and mass graves.

Day by day the truth recedes from view. It is concealed by thick grasses. Only a few fragments of bone and shreds of cloth reach from the earth and demand attention.

"The blood is speaking," said "Papa" Isaac, a local translator with the UN in Tshimbulu town in the central Kasai region. He had brought us to the centre of a field where, he says, "the blood of my brothers is speaking".

Nobody knows how many bodies the army dumped here.

A woman working in a field nearby approached, curious at at the presence of UN soldiers. Her 12-year-old son was among those buried in the grave.

"The military were burying the bodies. We saw where they stopped and how they dug to bury the corpses… some were as young as 12," she sad.

"They did not only kill the militia. They killed innocent people."

Death and life-changing injuries haunt the people left behind

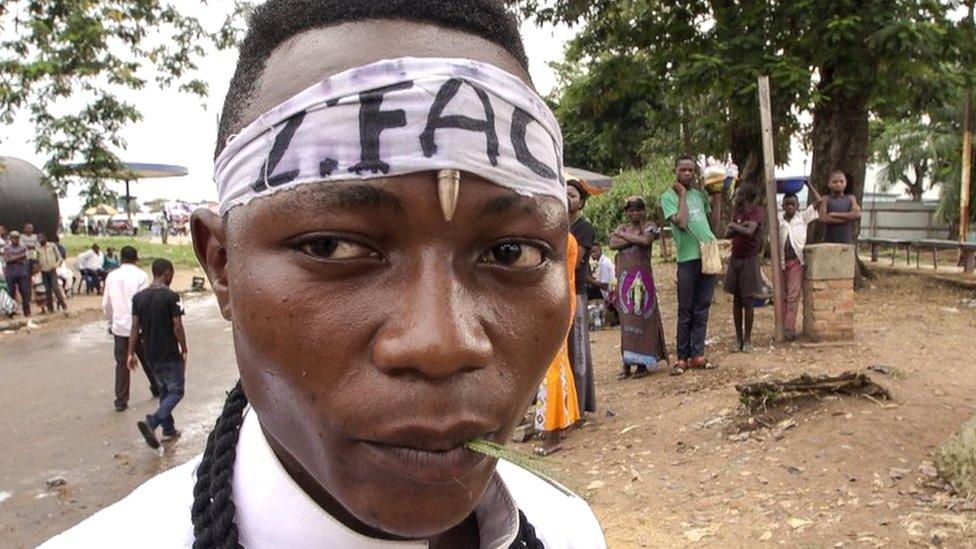

The violence began last spring when long-simmering resentment exploded into rebellion against a central government seen as remote and corrupt, whose police and army were feared for their brutality.

The spark was the refusal of the government to recognise a traditional chief, Kamina Nsapu, and the imposition of its own man.

In August the chief was killed by security forces, but his followers struck back, killing all whom they regarded as collaborators of the state.

In the fighting that followed, nearly 1.4 million people were displaced, among them around 850,000 children.

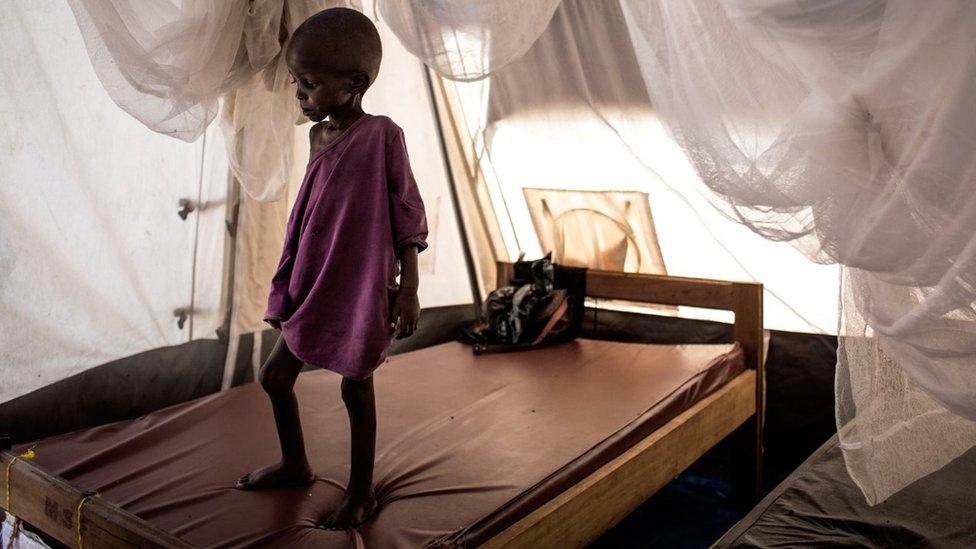

Kasai is now in the grip of a hunger crisis caused by the displacement of subsistence farmers who cannot plant crops to feed their families.

The Kasai road where everyone is hungry

In the two weeks we spent in Kasai, the consequences of violence were shockingly evident.

We saw it in the skeletal frames of malnourished children, the teeming crowds of women and children sheltering still in church buildings, and we heard the testimonies of those who had survived atrocities of immense cruelty.

There have been mass beheadings by militias. Villagers gunned down by soldiers.

A woman stripped, beaten, publicly raped and then beheaded because she was accused of treachery by the Kamina Nsapu militia. It forced her stepson to carry out the sexual assault.

A voter registration activist for elections due next year, Prosper Ntambue, became a target because he was regarded as a representative of the state.

His office was burned but he survived.

However, tragedy continued to stalk the family: his daughter and son-in-law were captured at a roadblock, taken away and beheaded.

Their crime? The son-in-law was an engineer who maintained roads for the government.

Millions are at risk of malnourishment after farmers were forced to flee

Mr Ntambue showed me a photograph of the couple's five children, taken when the family was still a family.

"Their children are orphaned and they have remained here. I take care of them now," he told me.

The state's response to the uprising was pitiless. The army and police turned their guns on militia members, often villagers armed with homemade weapons and wearing charms they believed would protect them from bullets. But civilians who had no link to the Kamina Nsapu were also killed.

In some areas the instability exposed ethnic rivalries, but it would be a grave mistake to characterise what took place as "ethnic" violence.

It was the violence of the poor and the alienated in a place where the state was anything but an impartial actor.

We spoke to numerous witnesses who described atrocities by the security forces and the Bana Mura militia, which supports the government. The witnesses asked us to protect their identities for fear of reprisal by the army.

By the side of the Kasai River in the town of Tshikapa a man pointed at the fast-flowing current. He was remembering the bodies toppling into the river to be swept away downstream.

"The military were taking people and throwing them into the river. People started to run away and hide. They followed them, killed them and threw them into the river," he said.

Soldiers are accused of throwing bodies off this bridge

Sheltering in a church building, a mother told us how three of her four children were beheaded by the Bana Mura militia. She pleaded with the army to intervene but they did not stop the killers. Her mind is flooded with the imagery of a night of killing.

"I saw people with machetes, guns and clubs. They were beheading people, cutting arms and legs, slashing bellies. I had to climb over dead bodies to flee," she said.

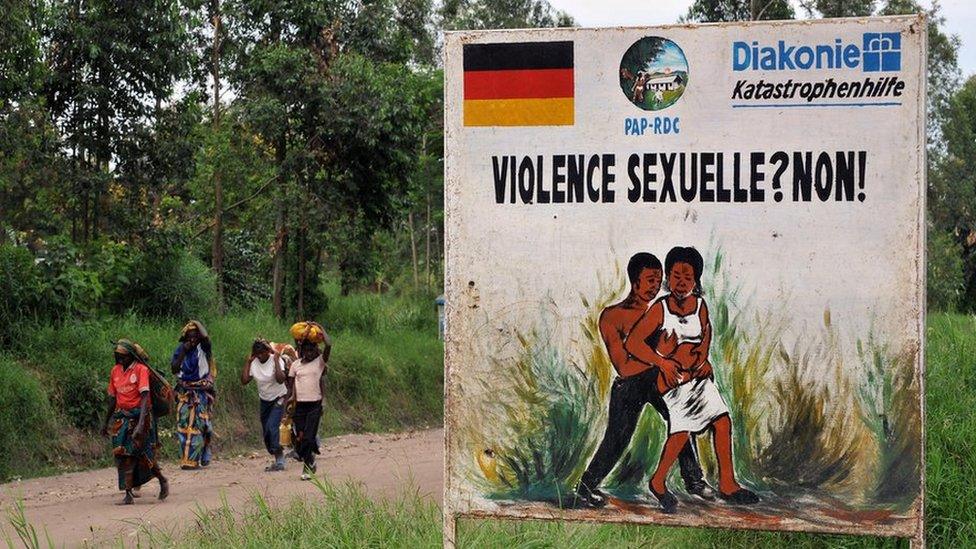

Another mother told how she and her 15-year-old daughter were taken by the militia to separate farms.

The child who sat opposite us did not look more than 12. In a low monotone her mother recounted how she had been violated so many times she could not count.

"I only found that my daughter had been raped afterwards," she said. "There is great bitterness in my heart that my child has been defiled. She is just a kid."

In Kasai, only the UN stands between the people and exactions of the state and different militias. Unlike eastern DR Congo, the UN does not work alongside the army in Kasai. It is a stance that speaks loudly about the army's record.

But the UN is under pressure. It has fewer than 20,000 troops in a country two-thirds the size of western Europe.

Even this relatively small force is being cut back by 3,000 as the United States moves to reduce the costs of peacekeeping.

Not all of DR Congo is under threat of violence but besides Kasai there have been renewed outbreaks in the east, where 15 peacekeepers were killed last week, and in Tanganyika where hundreds of thousands are displaced.

I asked the UN's chief in Kasai, Charles Frisby, what could be achieved with so few troops? "Quite simply imagine what would happen if they were not here," he replied.

It is not a vista anybody who has recently visited Kasai would wish to contemplate. The region bristles with subdued violence. There is no real peace to keep in Kasai, only a daily effort to hold back the forces of chaos.

All images copyrighted.

- Published13 December 2017

- Published6 December 2017

- Published25 September 2017

- Published24 April 2017

- Published9 October 2013

- Published31 January