Hugh Masekela: South Africa's 'Father of Jazz'

- Published

Jazz legend Hugh Masekela first picked up a trumpet in the 1950s: a time when the colour of his skin meant he was no more than a second-class citizen in his own country, South Africa.

Over the following decades, he would become known across the world for both his music and his role as an anti-apartheid activist.

Indeed, songs like Soweto Blues would provide the soundtrack of the movement.

By the time of his death at the age of 78 - almost 30 years after the fall of white minority rule - he was revered as South Africa's Father of Jazz.

Inspiration

Ramapolo Hugh Masekela was born on 4 April 1939 in KwaGuqa township, 100km (60 miles) east of the capital, Pretoria, part of a musical household.

"You know, everybody had a gramophone," he recalled. "My uncle, he had the greatest voice so he sang along with all the records - Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong."

The music and politics of legendary jazz trumpeter Hugh Masekela

Masekela began singing and playing the piano at an early age, it would be a Hollywood film about American jazz musicians which would inspire him to pick up the trumpet, aged just 14.

His first trumpet was given to him by British anti-apartheid activist Trevor Huddleston, a teacher at St Peter's Secondary School in South Africa who would later become an archbishop.

Masekela battled alcoholism and cocaine addiction

His talent soon becoming clear, Masekela and some of his schoolmates formed the Huddleston Jazz Band, South Africa's first youth orchestra.

Meanwhile, Father Huddleston had been banished from South Africa for his anti-apartheid activities. But this would provide Masekela with his next opportunity.

"Father Huddleston... met my idol Louis Armstrong and told him about our band. Louis's response was: 'Well‚ I got to send them one of my horns‚' and he did. What this did for the band was get us on the front page of every major newspaper and magazine in SA - a first for a black group," he told TimesLive.

But things were getting worse for black people in South Africa.

"We knew from when we were very, very young that we were black, and that we were looked down upon by white people, but we were not intimidated," Masekela told the BBC.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

In March 1960, more than 60 people were shot dead by police during a peaceful protest in Sharpeville. They had been protesting against a law meant to restrict their movement in white areas.

Masekela again turned to Father Huddleston to find him a way out of South Africa. Eventually, he got permission to leave for London.

"When the airplane finally took off, it was as though a very heavy weight had been taken off me - as if I had been painfully constipated for 21 years," he said in his autobiography.

He would not return for another three decades. But thousands of miles away, he never forgot the struggle of the family and friends he left behind under white minority rule.

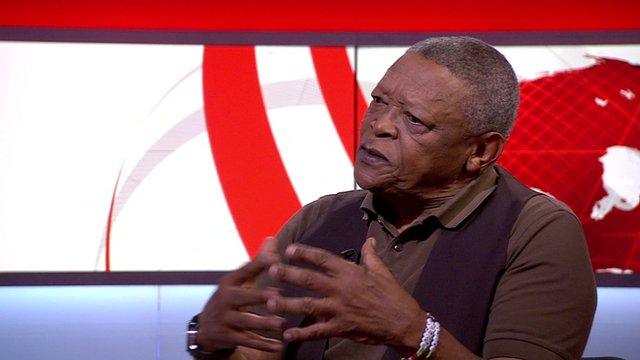

Hugh Masekela on music and his relationship with South Africa

The exploitation in South Africa inspired his music and his political activism. His music portrayed the struggles, sorrows, joys and passions of his countrymen.

In 1964, he married fellow South African musician Miriam Makeba - the singer who would later become known as Mama Africa. The marriage ended in divorce two years later, but they would continue to perform together throughout the years.

Masekela, pictured in 2015, was a vocal anti-apartheid activist

Masekela had also met American jazz singer Harry Belafonte, who, along with Makeba, encouraged the young musician to attend music school in New York.

It was here he met Armstrong, who had sent him the trumpet years before and was now a key player in encouraging to create his own style.

Recalling the meeting, he told the Wall Street Journal, external: "He asked if I sang. I told him I didn't. He said in that gravelly voice, 'If I can sing, annny-body can.'"

In 1967, he performed at the Monterey Pop Festival alongside Janis Joplin, Otis Redding, Ravi Shankar, The Who and Jimi Hendrix.

But it was the following year he would have his breakout song: the instrumental single Grazing in the Grass, which topped the charts in the US and became a worldwide hit.

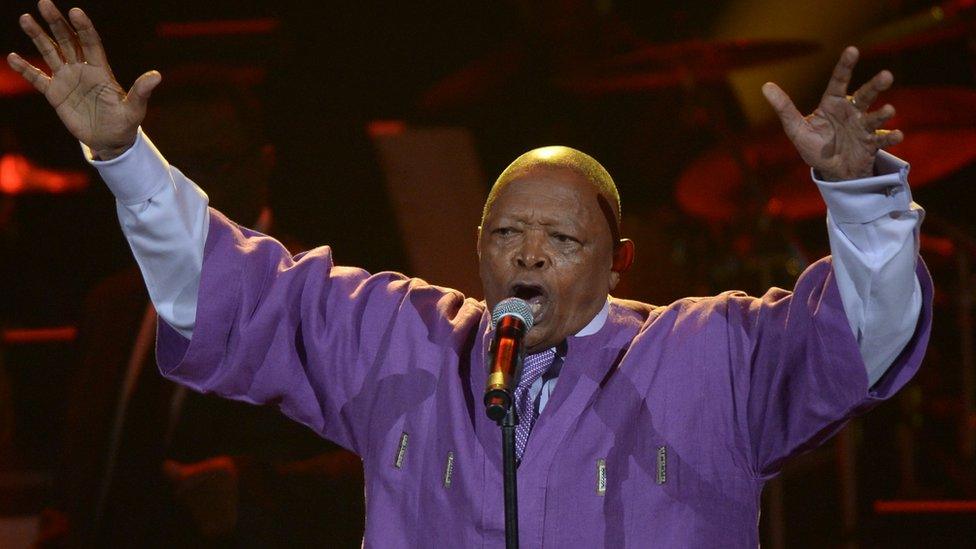

Masekela, here performing in August 2016, was born in a South African township

In the 1980s, Masekela - who had then settled in Botswana - went on to perform with Paul Simon on the Graceland tour, defending him when Simon was accused of breaking a cultural boycott.

In 1987 hit "Bring Him Back Home" became the anthem for Nelson Mandela's visits around the world after his release from prison.

When Mandela was finally released from prison in 1990, Masekela came home.

However, behind the scenes Masekela had his own struggles. He was battling alcoholism and a cocaine addiction he would only seek help for in 1997 - a habit he would later say cost him tens of millions of rands, the South African currency.

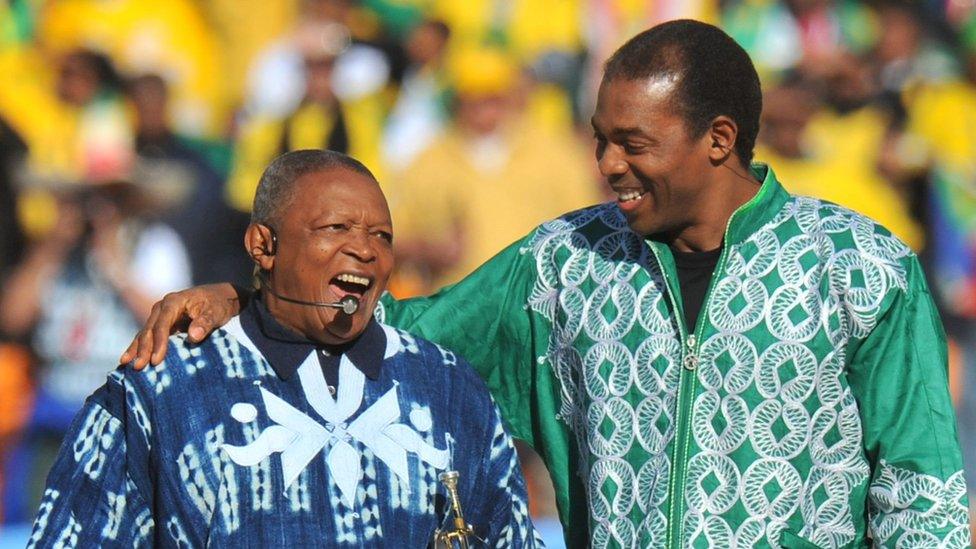

At the opening ceremony of the 2010 football World Cup alongside Femi Kuti

But he did not let his addiction beat him, and he set up a rehabilitation programme with other artists in 2001.

A diagnosis of prostate cancer followed in 2008, but this also failed to slow him down. In 2010, he took to the stage with Nigerian singer Femi Kuti at the opening ceremony of the football World Cup, which was being held in South Africa - a performance few could have imagined in Soweto just two decades before.

Two years later, he went on tour with his old friend Paul Simon to celebrate the 25th anniversary of Graceland.

Masekela finally lost his battle against prostate cancer. In his last years, his attention had turned to preserving South Africa's musical heritage, as well as battling xenophobia.

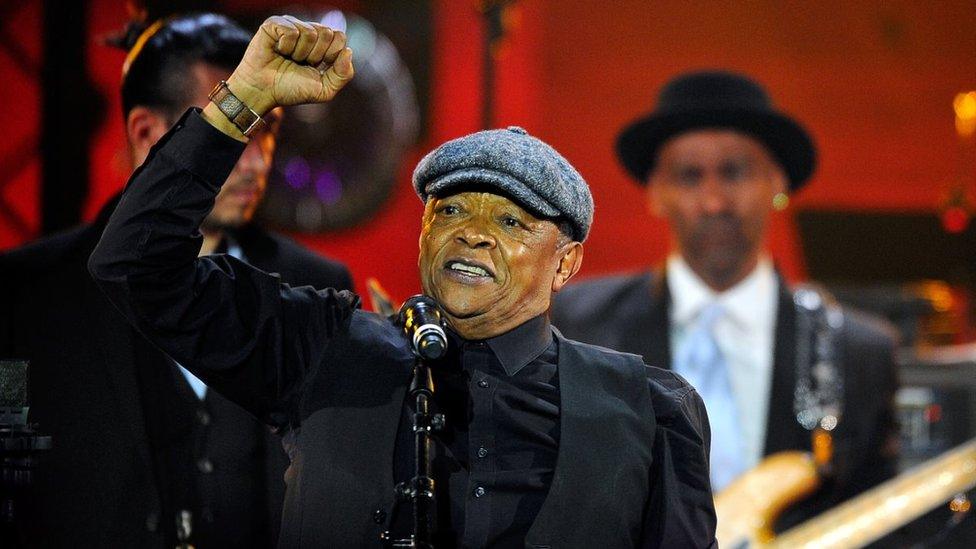

Performing with Paul Simons in 2014

As for his own legacy, he was less worried by that.

"I don't want to live beyond where I am now... and I live it day by day. And, I think once you get too involved with your legacy and all that, you are swallowed by your own ego," he told TshishaLive last year., external

However, his legacy will live on - and tributes from across the world flooded social media in the hours after his family announced his passing, not least the heartfelt tribute left by his son, Sal.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Ramapolo Hugh Masekela (4 April 1939 - 23 January 2018) is survived by his son Sal and daughter Pula Twala.

- Published23 January 2018

- Published9 June 2015