Why has Ethiopia imposed a state of emergency?

- Published

The government is considering imposing a curfew as part of the state of emergency

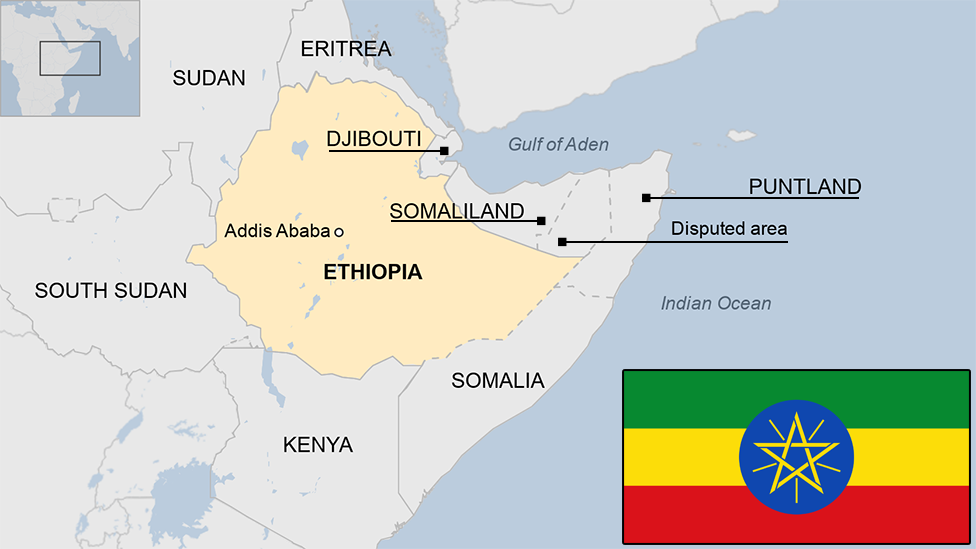

Ethiopia, the second most populous country in Africa and one which has seen a booming economy recently, has been shaken up in the past week.

First Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn unexpectedly resigned after five years in power.

Then a national state of emergency was declared the next day.

A statement by the state broadcaster said the move was necessary to stem a wave of anti-government protests.

Hundreds of people have died in three years of unrest, and this is the second time since 2016 that a state of emergency has been declared.

What does the state of emergency prevent?

Preparing, printing or circulating any information that could cause disturbance or suspicion

Displaying or publicising signs that could stir up violence

Protests and any form of group assembly

The halting of public services by anti-government protesters

The closing of businesses by anti-government protesters

The government also retains the freedom to shut down the media and impose a public curfew, details of which have not been released.

Under the conditions of the state of emergency, any person shutting down businesses or public services will face court action.

Why was a state of emergency declared?

Ethiopia has been hit by three years of protests

The government gave three key reasons:

To ensure peace and political stability

To respond to the resignation of the prime minister

To facilitate a peaceful transition of power

However, some analysts say the order lacks legal basis and that claims about instability are not true. Instead they view the state of emergency as a warning to those who might try and cause trouble when a new prime minister is appointed.

Local activists are worried that another government measure might be aimed at further quelling dissent.

In January, officials released more than 3,000 political activists and journalists from prison including opposition leaders Bekele Gerba, Merera Gudina and Andualem Arage.

Opposition leader Merera Gudina is the highest profile prisoner to have been released so far

Activists say that the government might be releasing prisoners now to make space for others later.

But the authorities say the pardons are part of a move to create a national consensus and widen democratic participation.

The state of emergency, opponents say, contradicts that.

How has life changed since the state of emergency was announced?

For most people across Ethiopia, life is continuing as before. In the capital Addis Ababa, shops are open and people are going about their business as usual.

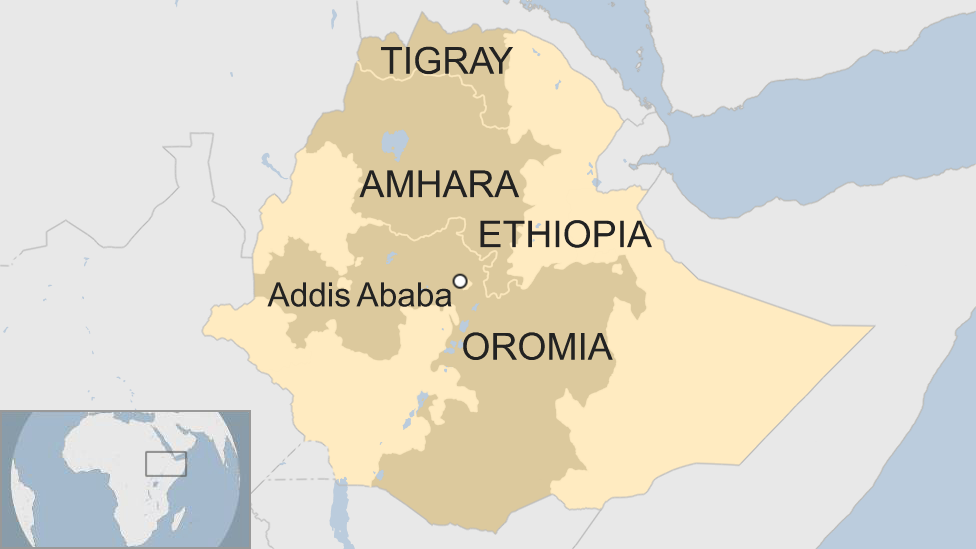

But in some areas of Amhara state, people are defying the authorities by closing their businesses and halting transport services.

The government reportedly responded by forcing residents to reopen their shops.

Similar disobedience has occurred in Oromia where large crowds have gathered to welcome the released prisoners.

In some cases, the crowds have chanted slogans against the ruling party, but have not faced reprisals.

Why did the prime minister resign?

The governing coalition, the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), is extremely secretive and it is hard to know exactly what is going on.

But since coming to power, some in the political elite have accused Mr Hailemariam of being weak and lacking in leadership.

Hailemariam Desalegn had been Ethiopia's prime minister since 2012

His resignation could be a move by the governing coalition to find a stronger leader, or it could signal divisions among the constituent parties along ethnic lines.

Particularly visible is the tension between the Tigrayan People's Liberation Front (TPLF), which has seen its dominance and influence wane, and the Oromo People's Democratic Organisation (OPDO), which is becoming increasingly assertive.

Replacing Mr Hailemariam with someone from the Oromo community might also be one way to meet the demands of Oromo protesters who have accused the authorities of marginalising them.

Ethiopia has never had an Oromo prime minister, even though they are the country's largest ethnic group.

Ethiopia's ethnic make-up:

Oromo - 34.4%

Amhara - 27%

Somali - 6.2%

Tigray - 6.1%

Others - 26.3%

Source: CIA World Factbook, external estimates from 2007

Who will the new prime minister be?

Lemmy Megersa, regional state president of Oromia and head of the OPDO, is among those hoping to become prime minister.

Other contenders include Debretsiyon Gebremikael of the TPLF, Demeke Makonnin from the Amhara National Democratic Movement and Werkineh Gebeyehu and Abiyi Ahimed of the OPDO.

All three parties are members of the governing EPRDF coalition.

Why are people protesting?

A number of grievances have driven popular protests throughout Ethiopia over the last three years:

Many Oromos say they have been politically, economically and culturally marginalised for years despite being the country's largest group

Some in the Amhara community have also complained about the dominance of the small Tigrinya group

Opposition groups and human rights campaigners want the EPRDF to release its tight grip on power and allow them to operate freely

People across the country have complained about human rights violations including the imprisonment, torture and extrajudicial killing of political dissidents

Land grabs and displacing groups of people under the guise of development and investment without providing proper compensation - one trigger for the protests was a plan to expand the boundaries of the capital Addis Ababa into Oromia province, although that plan was later dropped

More about Ethiopia:

Energy from rubbish to power Addis Ababa

Can Ethiopia be Africa's leading manufacturing hub?

You can now get the latest BBC news in Afaan Oromo, Amharic and Tigrinya.

- Published24 August 2017

- Published15 February 2018

- Published2 January 2024

- Published4 January 2018