Can Ethiopia's Abiy Ahmed make peace with 'Africa's North Korea'?

- Published

Abiy Ahmed made the historic trip to Eritrea to meet President Isaias Afwerki

Rarely is history made so vividly and swiftly.

Two nations that were bitter enemies for half a century, who fought wars that left tens of thousands dead and many more displaced, have embraced peace in the space of a few days.

This is very big news not only for Africa. The rapprochement between Ethiopia and its smaller neighbour Eritrea offers an example to the world of what is possible with bold leadership.

The man largely responsible for this change is one of the most dynamic and charismatic politicians to emerge in modern Africa.

A former army officer, who holds a doctorate in conflict resolution, Abiy Ahmed was elected prime minister of Ethiopia by the country's ruling coalition in April.

When Mr Abiy embraced his counterpart, Eritrea's long-standing strongman, Isaias Afwerki, it was the latest and boldest move from a prime minister who has stunned his own people and energised pro-democracy activists across the continent.

Crowds turned out to greet Ethiopia's prime minister after he flew into Eritrea's capital, Asmara

A country that was for so long stereotyped in the West as a symbol of all that was wrong in Africa - the nation of famine and Bob Geldof's BandAid - is evolving into a standard-bearer of change.

The 42-year-old former army officer has freed political prisoners, sacked officials accused of abuses, lifted press restrictions, began to liberalise the economy and has now - with the help of President Isaias - ended the war with Eritrea.

At its worst, the bitterness between the two nations reduced children like Adonay Michael to shivering, traumatised ghosts.

Bitter hostility

I met him in the mountains of Eritrea after the Ethiopians bombed his local market.

He was caught out in the open with his sister when napalm canisters were dropped into the crowds, spreading liquid fire that ravaged his skin.

Adonay was about 10 years old and cried out in agony whenever the wind blew through the tent where he lay.

This was more than 30 years ago when Eritrean guerrillas were fighting for independence from Ethiopia.

People in Asmara celebrated what they called an historic meeting between the two leaders

As both sides espoused versions of Marxist ideology this was not a battle over ways of seeing the world, rather this was in essence an Eritrean nationalist struggle against domination by a larger neighbour.

All through my journey I encountered the victims - civilian and military - of this war.

And so it would continue. Apart from a five-year period after Eritrean independence in 1993, bitter hostility has defined the relationship between the two nations.

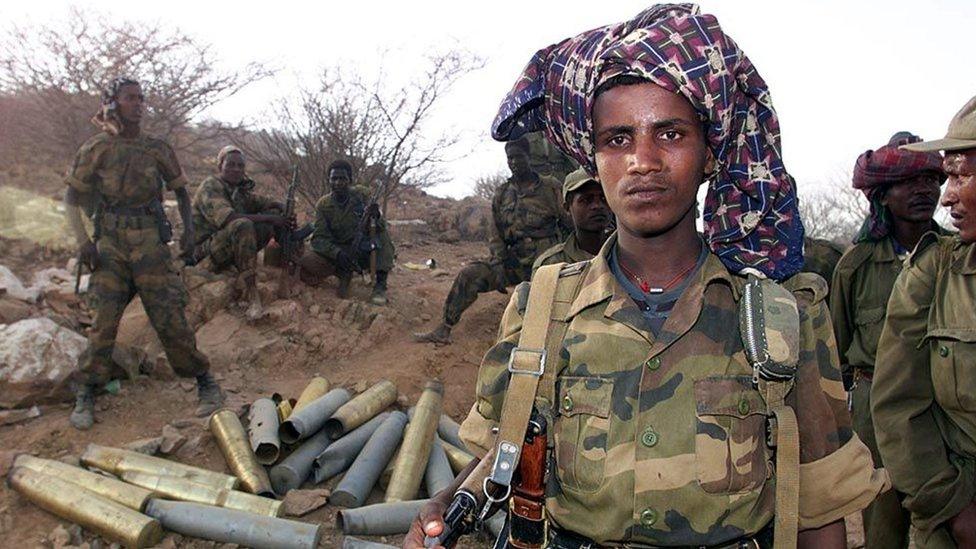

A border war between 1998 and 2000 left 70,000 dead.

Ethiopia says it will withdraw its troops from the Badme region, as Eritrea has long demanded

But now the conflict has been officially declared to have ended. The two countries are to re-establish diplomatic relations. Flights between the two national capitals will resume.

When the streets of the Eritrean capital filled with cheering crowds to welcome the Ethiopian leader, an obvious question arose: what will be the impact of his liberalising crusade on his partner in peace, Mr Isaias, who leads one of the world's most secretive and repressive regimes?

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

I met Mr Isaias back in the 1980s in a cave high in the mountains of Eritrea when he was the leader of the secessionist guerrilla war against Ethiopia.

Back then he was cast as the leader of an heroic struggle against the Soviet-backed Derg regime in Addis Ababa. Mr Isaias, now 72-years-old, came across as flinty and utterly self-possessed.

Africa's 'North Korea'

As leader of an independent Eritrea, he has presided over the exodus of hundreds of thousands of his people fleeing repression and economic stagnation.

For those who reported on the migration crisis of 2015, it was striking how many Eritreans were among those arriving on European shores or who found their way to the "Jungle" camp in Calais.

All those I interviewed described an atmosphere of unrelenting fear in a country sometimes dubbed Africa's North Korea.

The UN has accused his government of actions that "may amount to crimes against humanity".

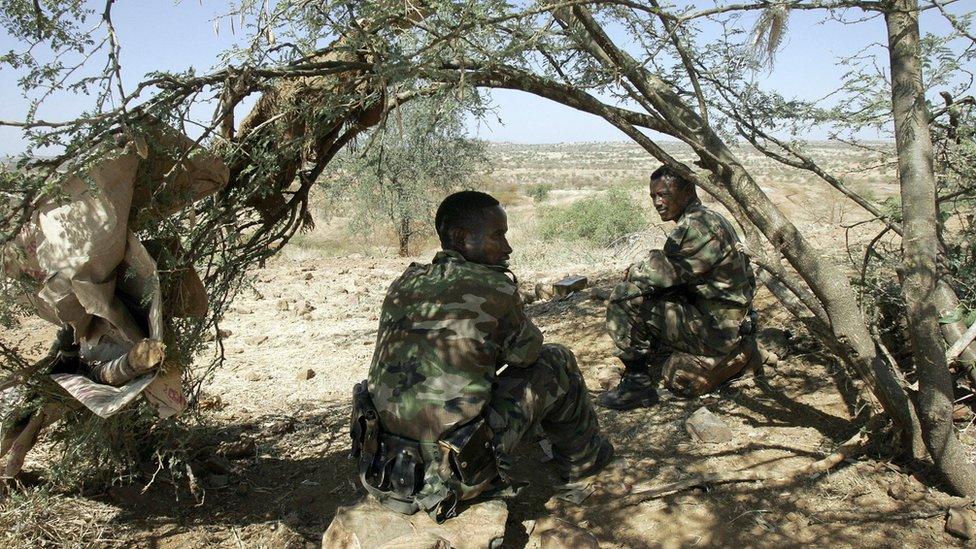

Thousands of young Eritreans have made dangerous journeys to escape forced conscription

Mr Isaias needs investment and financial aid and this probably explains his willingness to respond to Ethiopian overtures.

But he is 30 years older than Prime Minister Abiy and represents an idea of politics rooted in the totalitarian ideas of a different era.

So far he has given no indication that he plans to liberalise in the manner of his Ethiopian counterpart.

That may change if Mr Abiy can sustain the momentum of his reform programme.

The energy released by his visit, followed by a normalisation of relations between the two nations, is surely the first step in ending Eritrea's self-imposed isolation.

Mr Abiy's supporters have likened him to Mahatma Gandhi

It could also help shape the future of other nations in the region where corruption and misrule have been endemic.

Coming from a mixed Muslim-Christian background, Mr Abiy has also championed religious and ethnic tolerance.

Ethiopia has been ruled by the same coalition - the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front - for 27 years.

As the political space is opened up, there will be challenges to that dominance.

Nobel Prize?

Success will depend on Mr Abiy not only managing a successful political transition in Ethiopia, where political and ethnic rivalries have caused immense suffering in the past, but defeating those elements of the old state security apparatus responsible for past oppression.

At the moment his support is immense with vast crowds celebrating his reforms. But a grenade attack at a recent rally was a reminder of the perils he faces.

In an age of world politics when the loudest voices are so often discordant and divisive, the quietly spoken Ethiopian leader represents a striking contrast.

He has taken risks for change and peace that will surely bring him to the attention of the Nobel Prize committee.

It is of course early days but not too early to acknowledge the arrival of an extraordinary politician on the world scene.

- Published5 June 2018

- Published11 October 2021

- Published6 May 2018