Why Ethiopia is grieving for 'hero' dam engineer Simegnew Bekele

- Published

The death of Simegnew Bekele, the project manager of the multi-billion-dollar Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, has been met by an outpouring of grief in Ethiopia.

Condolences flooded social media from journalists, businessmen academics, ambassadors and even flag-carrying Ethiopian Airlines after it was reported that Mr Simegnew's body was found in a car in the capital, Addis Ababa, on Thursday.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The police are investigating the circumstances of his death. He died as a result of a bullet wound and a hand gun was found in his car, which was parked in Meskel Square in the city centre.

By the afternoon, hundreds had taken to the streets in the capital, as well as Mr Simegnew's hometown of Gondar, with protesters demanding "justice" for the late engineer.

To understand why a project manager has managed to elicit such shock and widespread mourning - normally seen in other countries after the death of royalty, celebrities or politicians - one has to look at what the Grand Ethiopian Dam has come to represent.

'Patriotic ambitions'

Straddling the Nile, the dam has been called the most ambitious infrastructure project ever achieved on the continent. Once built, the 1.8km (1.1 mile) wide and 155m (500ft 5in) high dam will triple the country's electricity production.

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, which is set to be Africa's biggest hydropower plant, is one of a number of large-scale infrastructure projects aimed at putting Ethiopia on course to become a middle-income nation by 2025.

Its scale and potential has brought rare unity in the country, which has faced political and ethnic strife over the years, Beletu Bulbula Sorsu, editor of BBC's Afaan Oromo Service, says.

"The project unites Ethiopians," she says.

The authorities says Mr Simegnew is going to get a funeral "a national hero deserves"

Matina Stevis-Gridneff, Africa correspondent for the Wall Street Journal who knew Mr Simegnew, says he has come to represent these patriotic ambitions.

"He was someone who was extremely patriotic and had devoted his life to the betterment of his country," she told the BBC'S Focus on Africa radio programme.

"He seemed to have devoted his entire life to Ethiopia's future by contributing what he could, which was his engineering skills."

Not a 'big man'

The 53-year-old gained his degree in civil engineering from Addis Ababa University and went on to to lead two other dam projects - Gilgel Gibe I and Gilgel Gibe II dams.

The new dam will regulate the flow of the Nile

He came to the public's attention in 2011, when he was put in charge of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.

Ms Beletu says he was frequently interviewed by the press and was widely perceived as being uncorrupted, modest and accessible.

"He was not a 'big man,'" she says of Mr Simegnew's honest nature.

"He behaved as if he was one of the the labourers working on the project."

Read more

Tibebeselassie Tigabu, from the BBC's Amharic Service, interviewed Mr Simegnew days before he died.

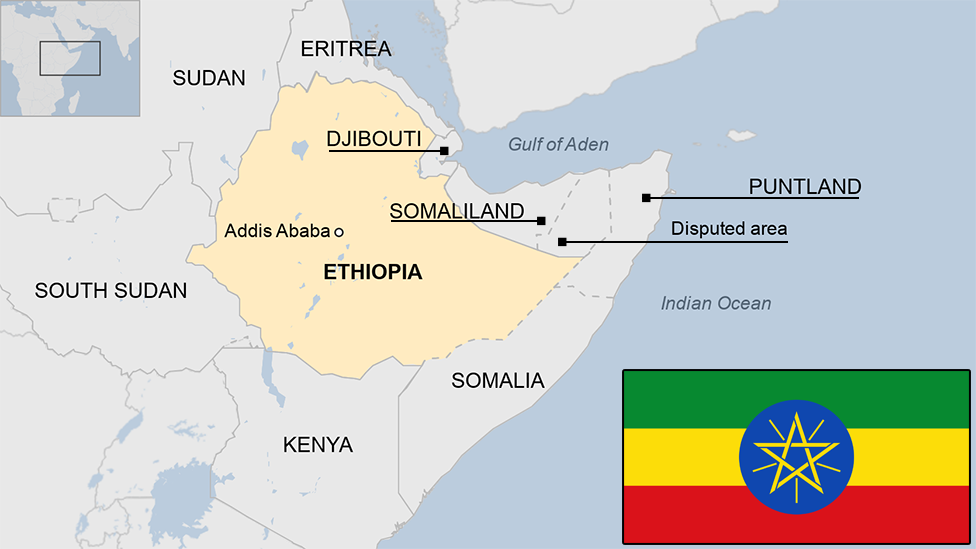

"He gave his life for the dam," she says, explaining that he spent most of his time around the dam, which was located in Ethiopia's Benishangul-Gumuz region near Sudan, nearly 1,000km north-west of his home in Addis Ababa.

"It is a difficult place to live and he had been there for more than six years," she adds.

A man of symbols

Mr Simegnew became the symbol of the dam and his death might become emblematic of the problems facing the project.

"He was the spokesman for the project, he was the front man and I am not sure how that will be replaced so easily," Ms Stevis-Gridneff says.

The dam is believed to be 60% complete, but there has been growing anger over delays.

In the last week of July, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed said that at the current pace of construction the dam might not be completed in the next 10 years.

Ethiopians are proud of the fact that the dam is a largely self-financed project. But a dollar shortage crisis has slowed down its construction, Ms Stevis-Gridneff says.

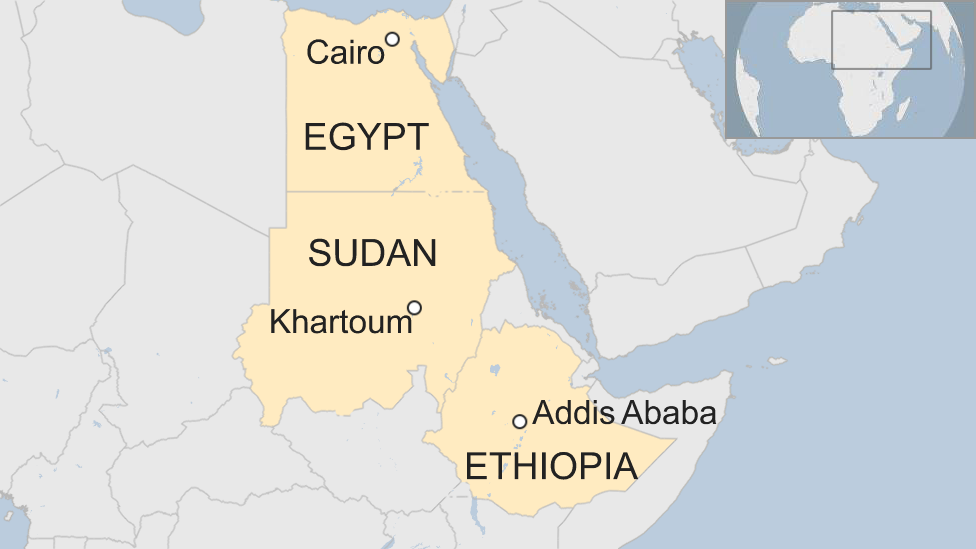

Then there is geopolitical tension the dam has created downstream with Egypt worried that the infrastructure project will put a strain on its water supply.

"While the project is coming into trouble for practical reasons, I also see his death as a real blow to the symbolism of this project and how it was recorded in the psyche of normal Ethiopians," she says.

Mr Simegnew was expected to be buried a day after his death. But a statement by a national committee set up to organise his funeral said it had postponed the burial.

They have instead made arrangements for a bigger funeral on Sunday 29 July "that a national hero like him deserves".

- Published22 March 2014

- Published24 February 2018

- Published11 October 2021

- Published24 August 2017

- Published2 January 2024