Letter from Africa: The link between earth tremors, God and Nigeria's elections

- Published

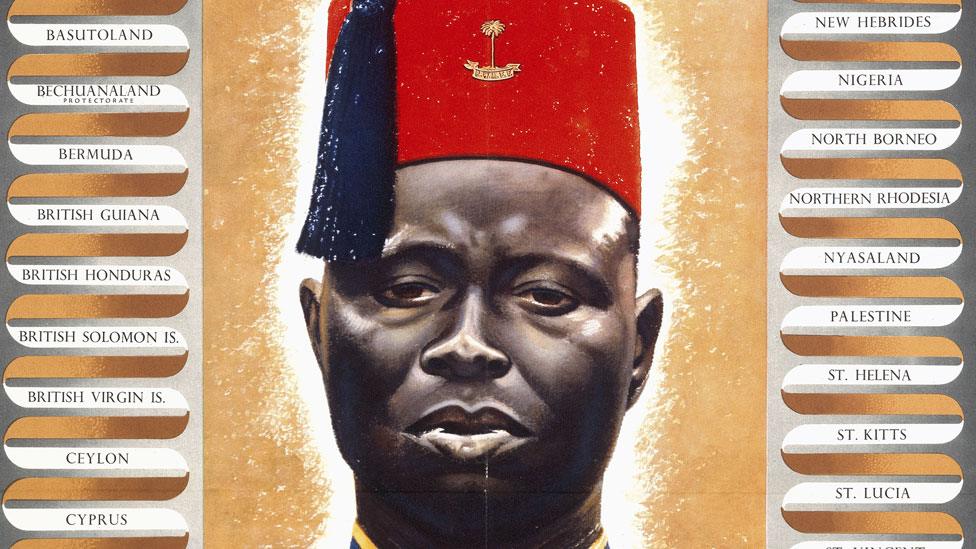

Nigeria's capital. Abuja, was disturbed by earth tremors earlier this month

In our series of letters from Africa, Nigerian writer and novelist Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani considers why some earth tremors in Nigeria's capital caused such a stir.

Sometime in the early hours of 6 September, I was tucked in bed at home in Abuja when, suddenly, a slight trembling seemed to sway the building from side to side.

My first thought was that a jihadist bomb had struck.

I still remember the exact moment in August 2011 when a Boko Haram militant drove a vehicle through two security barriers, crashed into the reception area of the UN headquarters in Abuja, then detonated a bomb, which left more than 20 people dead and more than 60 wounded.

I was in a nearby building, the offices of the now defunct Next newspapers, which rattled and quaked while we all flung ourselves to the ground.

In 2011, the vehicle carrying the bomb broke through two security barriers at the UN HQ in Abuja

But, when I didn't hear the wailing sirens that always followed bombings in Abuja, I relaxed.

Perhaps the trembling was simply an after-effect of the quarrying that sometimes takes place near my Asokoro neighbourhood and in other parts of Abuja, a city known for its imposing rocks.

A day of trembling

Later that day, frantic phone calls from friends checking to make sure that I was fine made me realise that what had simply been a mild trembling in my area was more tremulous in certain parts of the city, such as the Gwarinpa District, the location of a housing estate that is believed to be the largest in West Africa, and the Mpape suburb where residents, mostly-low income families, panicked and fled their homes in terror.

The tremors in Mpape began on the afternoon of the previous day and continued till around midnight, according to newspaper reports.

Residents described goods toppling off the shelves in their shops and fearing that the ceilings in their homes would cave in.

Many assumed that their buildings were about to collapse.

Barely two weeks earlier, the collapse of an incomplete building in the Jabi area of Abuja made news headlines. The scene of the disaster, in a modern neighbourhood with some upmarket estates, attracted a visit from Vice-President Yemi Osinbajo.

Protests followed the collapse of a half-finished multi-storey building in August

At the time, the government and residents disagreed over the number of dead, and there were protests when government rescue efforts ended barely 24 hours after the incident, with a number of victims still believed to be buried in the rubble.

A few days after the earth tremors, which were felt in different parts of Abuja between 5 September and 8 September, the government released a statement to reassure residents that there was nothing to worry about.

You may also like:

"We are carrying out adequate steps to determine what happened last week," said Idris Abass, head of the city's emergency management agency.

"Maybe it is a natural cause, but we want to assure the public that Nigeria is not on the zone of earthquakes."

Famous last words.

Back in June 2011, before the UN attack, a Boko Haram militant drove a car into the premises of the police headquarters in Abuja and exploded a bomb that took his life and that of a policeman.

Newspaper columns were taken up with analysing how the militant must have killed himself in error - probably a failed attempt to assassinate the police chief whose convoy the militant had tailed as it drove into the premises - as Nigeria was not a place known for suicide bombers.

The bombing of the police headquarters in 2011 is thought to be Nigeria's first suicide attack

Of course, we all know better now, what with the carnage the country has since witnessed over the past few years as Boko Haram attacks have intensified in northern Nigeria.

The police headquarters bombing is now regarded as Nigeria's first suicide bomb attack.

Quarrying activities banned

A day after Mr Abass' statement, another government agency published fresh information on the tremors.

The National Space and Research Development Agency (NASRDA) assured Abuja residents that there was no cause for alarm, although confirming that an earthquake had indeed occurred.

Agency head Seidu Mohammed said the magnitude was low and not worrying enough to warrant residents of the affected areas panicking and relocating elsewhere.

Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani:

"While government agencies have aired conflicting conjectures, many Nigerians, who tend to be deeply religious, have drawn their own conclusions"

Measures would be put in place to monitor the earth's movements so as to predict and prepare for any forthcoming disasters, he added.

Not long afterwards, yet another government official widened speculation by announcing the suspension of mining and quarrying activities in Abuja.

But Abubakar Bawa, minister of state for mines and steel development. emphasised that he was not concluding that "the tremors experienced may have anything to do with excavations around affected areas... until investigations are completed".

More Letters from Africa

While government agencies have aired conflicting conjectures, many Nigerians, who tend to be deeply religious, have drawn their own conclusions.

Some believe it is a sign that God is angry with our country about something.

Some believe that it is a warning to President Muhammadu Buhari; perhaps against his style of leadership or his intention to run for re-election in 2019 despite his lacklustre performance over the past three-and-a-half years.

Yet others believe that the earth tremors are simply a call to more fervent prayer for our nation, lest earthquakes soon join an already long list of headline-stealing tribulations that includes: Farmer-herdsmen clashes, the Boko Haram insurgency, ethnic agitations and the battered economy.

One can hardly imagine how Nigeria might handle earthquakes when the government is still battling to cope with these other disasters that have left millions displaced and in dire need.

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external or on Instagram at bbcafrica, external

- Published13 August 2018

- Published8 July 2018