Why does Nigeria keep flooding?

- Published

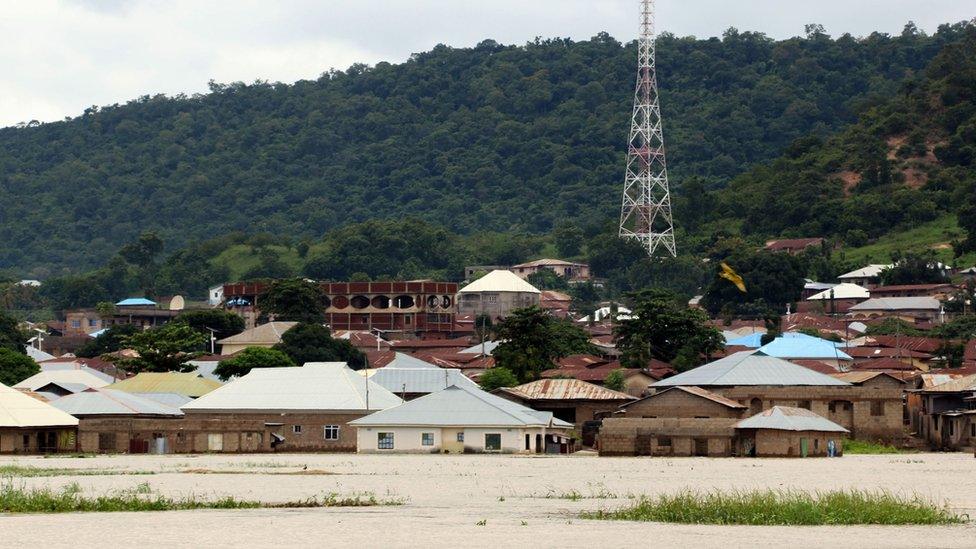

Lokoja, where the Niger and Benue rivers meet

Heavy seasonal rains are a regular feature of life in Nigeria and towns close to the country's main rivers are particularly vulnerable.

This year floods have killed almost 200 people with many thousands displaced.

The National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) say these figures are likely to rise as the full impact becomes clear.

A state of emergency has been declared in four of the worst-hit states:

Niger

Kogi

Anambra

Delta

President Muhammadu Buhari has pledged $8.2m (£6.2m) for relief efforts. The NEMA has activated five local operation centres to coordinate emergency responses.

Flooding regularly wreaks havoc in Nigeria:

In 2017, floods affected 250,000 people, external in the eastern-central region

In 2016, 92,000 were displaced, external and 38 died

In 2015, more than 100,000 were displaced, external, with 53 deaths

In 2012, devastating flooding forced two million Nigerians from their homes and 363 died, according to authorities

"Floods have become a perennial challenge with increasing intensity each year, leaving colossal losses and trauma," the Nigerian Meteorological Agency says.

So why does Nigeria keep flooding, and is it getting worse?

Affected areas

Flooding near Kaduna River

Nigeria hosts two of West Africa's great rivers:

the Niger which enters the country from the north-west

the Benue, which flows into Nigeria from its eastern neighbour Cameroon

These two immense waterways meet in central Nigeria and then flow south as a single river on to the Atlantic Ocean.

Much, though by no means all, of Nigeria's flooding occurs along these two rivers as their banks overflow in the rainy season.

In 2012, hundreds of thousands of acres of land were flooded in Nigeria when the Benue and Niger over-spilled.

That year, the Niger River reached a record-high level of 12.84m (42ft).

In 2018, levels reached 11.06m, with fears that the heavy rain, expected to continue through October this year, could lead it to approach similar heights.

There has also been extensive damage to farmlands, external, according ACAPS, a humanitarian data-analysis organisation, which is the mainstay of most livelihoods in the affected regions.

Flooding is also caused by:

the tidal movements of coastal waters, such as in the Delta region of the south-east

saturated drainage systems, such as in the country's largest city, Lagos, in the south-west

Are Nigeria's rains causing the floods?

Heavy rainfall has certainly increased the likelihood of rivers overflowing and flash floods.

And there's evidence to suggest increasing rainfall over time.

Data from the Nigerian Meteorological Agency from 1981-2017, analysing 13 affected locations, reveals a rising trend in annual rainfall, which it says is likely to be a significant factor responsible for floods.

But it's not just rain falling in Nigeria itself.

Heavy precipitation upstream on the Benue and Niger rivers - in Cameroon, Mali and the country of Niger - contributes large volumes of water to Nigeria's river system, according to Zahrah Musa at the IHE Delft Institute for Water Education.

Troublesome dams

Another factor in Nigeria's flood problem is dams.

Kainji dam

Nigeria's three main electricity-generating dams, at Kainji and Jebba on the Niger river and the Shiroro dam on the Kaduna River, "have become bloated" by the heavy rains and excess water has had to be released downstream over the past month, says Hussaini Ibrahim, of the Niger State Emergency Management Agency (NSEMA).

The uncompleted Zungeru dam, in Niger state, which is part-funded by the Chinese government, is also believed to be affecting areas once free from flooding.

On the Benue River, the main concern is the Lagdo Dam, in neighbouring Cameroon, which has previously caused the river to swell by releasing water.

In 2012, water flowing in from the Lagdo dam was blamed for 30 deaths, external in Nigeria.

The Cameroonian authorities have yet to allow water to pour out from Lagdo during the current rainy season - but there are concerns in Nigeria that this might happen.

Poor town planning

Nigeria's population is expanding rapidly, currently estimated at 186 million, and the lack of proper town planning can make flooding worse in urban areas.

"Town planning in Nigeria is very weak," says Aliyu Salisu Barau, of Bayero University. "These areas are affected by a lack of drainage networks."

The city of Lokoja, for example, at the meeting-point of Benue and Niger rivers, is particularly prone to flooding.

A man in a town near Lokoja, a heavily flooded area

"If you go to Lokoja, you see massive developments along the Niger River," says Mr Barau.

These developments are almost always unregulated, with people building on floodplains, reducing the surface areas for water to travel, and without constructing drainage systems.

Because of the unregulated nature of town planning, there's also limited information on how much land has been built on and therefore little assessment of the impact.

In the city of Makurdi, for example, on the Benue river, Mr Barau says, "one can see all forms of informal activities" along the river bank.

New land developments along the Niger River has more than doubled in Nassarwa and Kogi States, according to estimates.

The dumping of waste in the streets can also prevent the steady flow of water and put pressure on the few urban drainage systems.

It's also common, after the floods, for people to come back and start rebuilding in the same vulnerable areas.

Hussaini Ibrahim, of the NSEMA, also points the finger at deforestation, which he says is happening across Nigeria.

It's a resource that people use for fuel or to sell - but trees play an important role in storing rain-waters.

Future floods

If the impact of flooding is to be reduced in the future, the consequences of rapid urbanisation and poor urban planning need to be addressed.

And greater co-operation with Nigeria's neighbours in the control of river levels will need to be achieved in order to avoid dangerous surges in water levels during the periods of heavy rain.

The wider issue of the increasing rainfall levels identified by the Nigerian Meteorological Agency is one that some in Nigeria have attributed to climate change.