The Kenyan school which changed an American boy's life

- Published

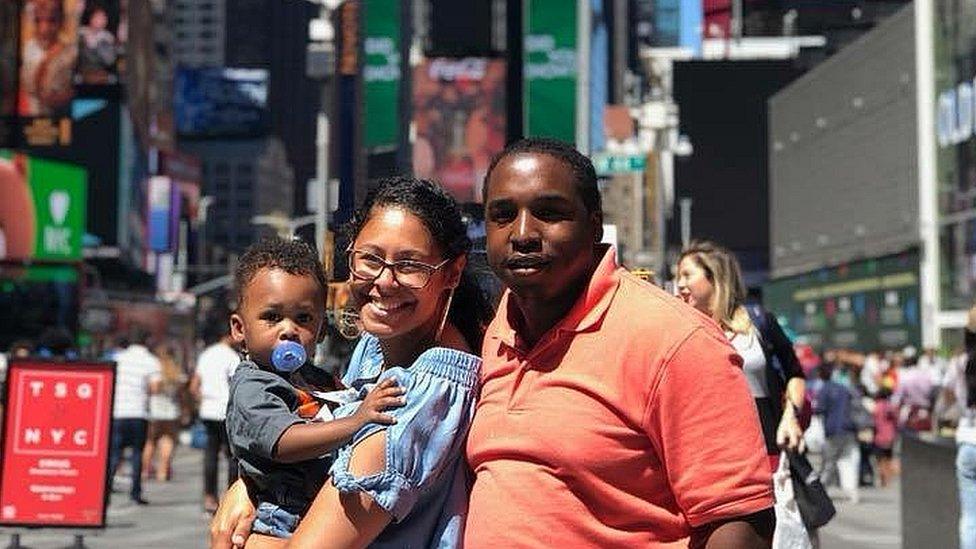

Devon Brown, pictured with wife Octavia and their son, Nehemiah, grew up with limited prospects

Devon Brown could easily have become just another statistic - one of the 486,900 black inmates in US state and federal prisons by the end of 2016.

But an academic year in Kenya during his seventh grade changed his life forever.

"Honestly it turned me into the man I am today. From a boy with limited options in inner-city Baltimore to a man who has now run an ice-cream company with revenues of $400,000 (£310,000) as its CEO," he reflects.

Mr Brown's childhood had all the ingredients for failure.

Born on 9 January 1990 in East Baltimore, his late mother was addicted to heroin and cocaine while his father drank too much.

Outside their house, the harsh streets of Baltimore only compounded the situation as drug dealers, addicts, broken families and a crowded school system offered little hope for a better future.

Baltimore has struggled with violent crime and drug misuse

By the time his grandparents took over parental duties, Devon was an angry boy, bitter about his circumstances with low self-esteem in tow.

"It was embarrassing to have a mum who was not stable and that was difficult for me to understand. When she was sober it was great but when the drugs took hold of her it was another case altogether," he told the BBC.

His sixth grade was a blur of school suspensions as he constantly found himself on the wrong side of the school administration.

'Exciting' opportunity

Then one day a recruiter from the Abell Foundation, a local non-governmental organisation, showed up at school and made a presentation to the sixth-graders.

In her presentation, Mavis Jackson told the boys about a school called Baraka (Kiswahili for blessings) that had been operating in Kenya since 1996.

The idea of Baraka came after the Abell Foundation met principals of schools based within the inner city and discussed ways to improve the academic performance of the students in their schools.

The principals told them to remove 10% of their students - those who had either refused to learn or could not be controlled - and the performance of the schools would improve.

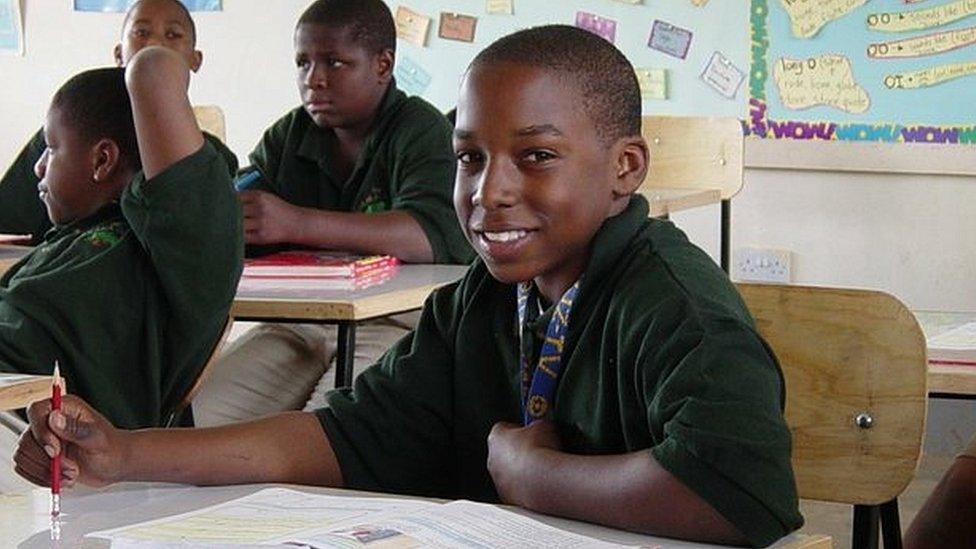

Devon has gone on to have a successful career

The Abell Foundation then decided to scout for a boarding school so that the errant students could learn in a new environment.

They considered other, more remote, parts of America but the school would have been too expensive to run there.

They also looked at West Africa as a possible location but other barriers emerged so finally they settled on Kenya in East Africa. It helped that the people were English-speaking and the climate was mild.

Devon recalls the day, aged 12, he first heard about Baraka school.

"I was so excited about this opportunity. I had never been to any airport, let alone on a plane, so this was beyond my wildest dreams," he told the BBC.

After a lengthy application process with an interview to boot, he found himself on a plane headed to Kenya on 12 September 2002, with 11 other boys.

Culture shock does not adequately describe what they experienced as they landed at Nairobi's Jomo Kenyatta International Airport on that warm morning.

Their journey from the airport to Nanyuki town, about 250km (155 miles) away, was one of discovery.

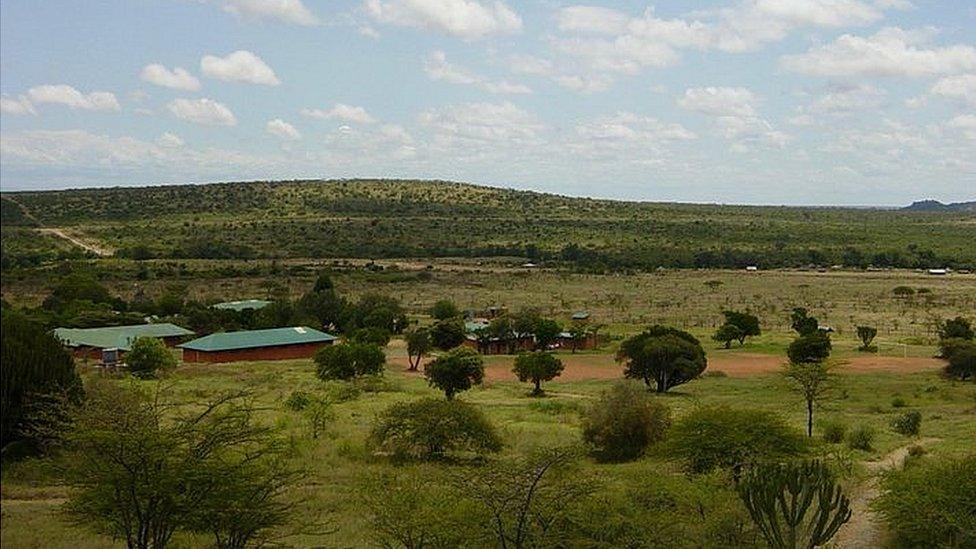

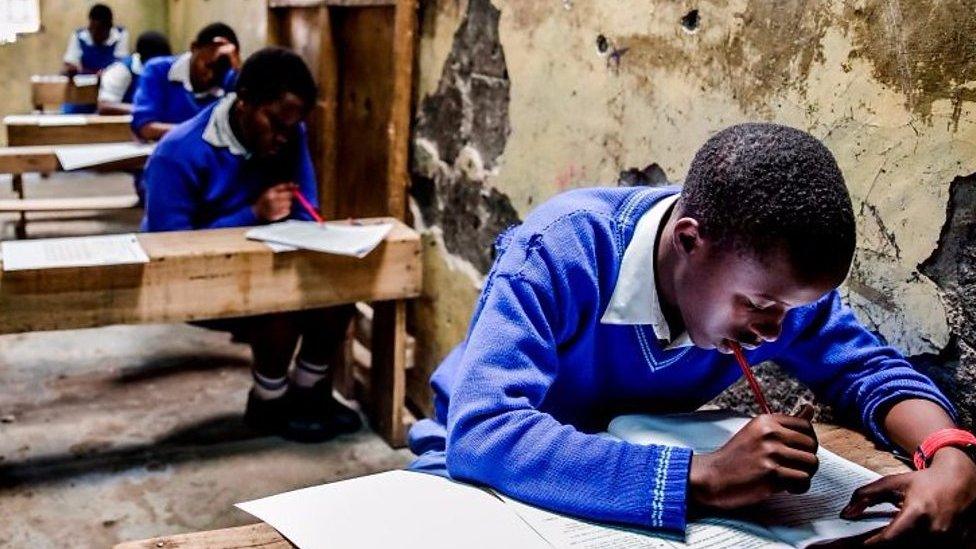

The school was in a remote town in Laikipia county

"I can still remember driving into Nanyuki and seeing hawkers trying to peddle their wares on the street, while at the same time fighting for space with herdsmen guiding their cows and sheep on the road. That was an unreal sight for this boy from Baltimore," he remembers.

'Out of this world'

Finally they arrived at Baraka school in Dol Dol, a small town near Nanyuki.

While the boys had grown accustomed to all the amenities of a US city, they would now have to contend with limited electricity supply, no fast food, no video games and wild animals as their nearest neighbours.

Adjusting was no mean feat and one of the boys even unsuccessfully tried to run away when the going got tough.

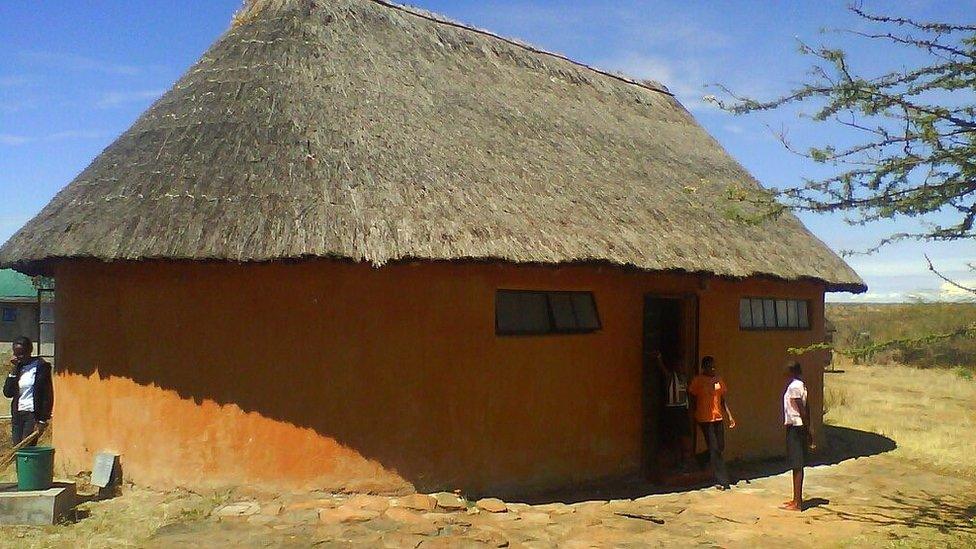

The dormitories at Baraka school were in traditional Kenyan style

The boys spent their weekdays in class learning the same subjects as back home, with the regional language of Kiswahili the only addition.

"What made learning at Baraka so effective was the small classroom size, attentive teachers, few distractions and peaceful environment away from crime. The boy's average attendance in Baltimore was 60%, while at Baraka they had no choice but to achieve 100%," Abell Foundation president Robert C Embry Jr told the BBC.

At weekends they could engage in various activities depending on how well they had behaved that week.

"I remember touring the national park around us and seeing these amazing animals. We would also leave the school and go swimming in town or play basketball and football with visiting teams. We even climbed Mount Kenya which took like three days… totally out of this world."

This combination of dedicated class sessions and memorable extra-curriculum activities had the right effect on the boys as their academic performance, including in maths and reading, improved considerably.

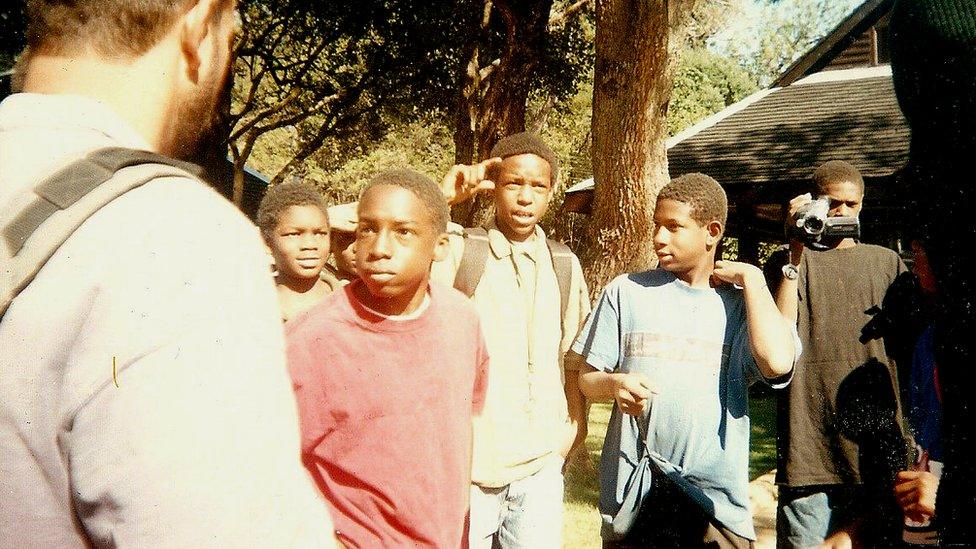

Devon Brown, being served, discovered a taste for Kenyan cuisine

The year passed by quite quickly and just before the summer break they returned to the US expecting to be back in September 2003 for the new academic year.

But that did not happen as the US State Department had issued a travel advisory about Kenya in May 2003 urging Americans to defer non-essential travel to Kenya.

"They closed the school down during that summer because there was unrest in the country and they told us that they would have to suspend the project. The embassy had even been temporarily closed. It was so unfortunate," he recalls sadly.

A total of 120 American boys had passed through the gates of Baraka school over a seven-year period.

The young Devon, in red shirt, thrived in his new environment in Kenya

Devon found renewed focus and a deeper faith in God after the year in Kenya. He finished his high school and later graduated from the Maryland Institute College of Art.

His year away in Kenya, together with the release of a documentary titled Boys of Baraka in 2005, had raised his profile in Baltimore and he gave a lot of talks to various groups about his experience.

'Life turned out pretty well'

During his college years he was asked to join the board of the Taharka Ice Cream Company.

Devon was a good brand ambassador for the company named after Taharka McCoy, a 25-year-old local mentor who was senselessly gunned down in January 2002.

The company's goal was not just to turn a profit but to also inspire young entrepreneurs from the inner city.

After Devon graduated from college, he was promoted to become the CEO of the ice-cream company and he boasts of raising revenues from $100,000 per year to $400,000 while he was there.

Devon says small classroom sizes, attentive teachers, few distractions and a peaceful environment helped him learn

He now runs his own marketing company in Maryland while taking care of his family of three together with his wife, Octavia Brown.

"My life turned out pretty well. In addition, some of the guys we went to Kenya with are doing well but others not so well. They are still into drugs and other misdemeanours. Everybody had to make their own choices I guess," Devon told the BBC.

He dreams of taking his family of five to Kenya one day to show them the school and land that changed his life.

"We got to interact with boys in the neighbourhood learning in small classrooms and it made me feel appreciative of the small stuff back in Baltimore and what I have.

"Also I learned that Africa is not all bad. Not everyone is poor on the continent. Not everyone is struggling. There are no naked people running around every five seconds like they show in the movies."

- Published2 February 2018

- Published3 October 2017

- Published4 July 2023