What we’ve learnt about fake news in Africa

- Published

Many overestimate their ability to spot fake news, a BBC report has found

People's emotions trump reason when it comes to sharing news, the BBC's in-depth research project Beyond Fake News has found. The spread of fake news can also undermine legitimate news because it erodes trust.

By analysing fake news messages on private networks like WhatsApp and Facebook, and surveying people in Nigeria, Kenya and India, researchers have pinpointed the motivations, anxieties and aspirations that drive it.

The study also help us understand the relationship between fake news and mainstream politics on digital networks.

Why does fake news matter?

Erodes trust

Builds and feeds on community divisions

Threat to a notion of truth

Toxic for mainstream media - all media given the same equivalence

Makes citizens less able to make decisions based on facts

Toxic for public discourse

Threats to health

Worse case scenario - fuels hate speech, leads to violence and death

Distorts democratic processes

Weaponises information

Why are people fooled by fake news?

Many overestimate their ability to spot fake news, the BBC found when speaking to social media users in Nigeria and Kenya.

Although many people understand the consequences of sharing fake news, that is often only on a conceptual level. Researchers found that the link between disinformation and things like electoral manipulation and democracy is too abstract for users to grasp.

Emotions trump reason when it comes to sharing news, the team found. "After watching the news I was touched, so I had to post it," said one interviewee in Nigeria.

Nigeria and Kenya have lower levels of digital literacy say researchers, especially in rural areas, where Facebook may be seen as synonymous with the internet and there all things on it may be seen as "true".

Fake scare stories about health, like this one, are often shared

But Nigerians and Kenyans do better than Indians when it comes to checking for themselves if a dubious story is true, which they do through search engines like Google or verifying with others in their network, among other things.

Some fake news is harder to identify than other kinds.

While users show a fair amount of scrutiny on political updates especially in Nigeria, they are less stringent if a news story positively affirms an aspect of their identity. That could be a story on ethic identity in Kenya for example, or an issue relating to geopolitics such as Nigeria's oil-rich Niger Delta.

But young people are less focused on ethnic and religious allegiances than the generations before them, and so are less likely to be driven by these identities when sharing fake news.

Why else do people share fake news?

Often they care more about who the sender is than the source. They might trust that a story is true because the sender is someone they trust to share worthy news, as opposed to a "pointless spammer".

Sharing news is socially validating too. Being the first to share a story in your group of friends, showing others you are in the know and provoking discussion make social media users feel good. Sometimes people will rush to share information not knowing if it is true.

Reading is hard, but sharing is easy. Researchers found most people do not consume their online news in-depth or critically, and many users will share stories based on a headline or image without having digested it in detail themselves.

For some, it is a civic duty. They will share information, regardless of its veracity, because they want to warn and update others. "Maybe there is a person who didn't know about it, and [I share the story] to avoid something like this happening to my friend, " one of dozens of people surveyed in Kenya told the BBC.

This story is part of a series by the BBC on disinformation and fake news - a global problem challenging the way we share information and perceive the world around us.

To see more stories and learn more about the series visit www.bbc.co.uk/fakenews

These users often strongly believe that access to information is stifled or unequal, and want to do their part to democratise it.

Other people choose to read known fake news sources simply because they find it entertaining. "[Even] though it ain't real, I just like the gossip," explained one of the Kenyan readers surveyed, Florence.

How can I spot fake news?

If you are unsure if a story is true, fact-checking website Africa Check, external is a good place to start.

Africa Check, external and others are working on creating data banks for people to source accurate data. But timeliness and speed in checking fake news or misinformation can be a challenge.

Remember that comments sections on mainstream media and Facebook cannot always be trusted, because it is a place where fake news is debated and amplified. Money and jobs scams are commonly found there, say researchers who analysed posts in African users' networks.

As things stand, many users say they end up relying on their instinct as to whether a story "feels" true, and whether they can find it reported by other sources.

"I look at the headlines. If it's too flashy then it's probably fake," a woman in Kenya called Mary told the BBC.

"Whenever I read something on the blog I double-check it, whichever blog I am reading something on I Google search it, I want to read two articles," said Chijioke in Nigeria.

What is fake news and how can you identify it?

But these two methods are far from foolproof.

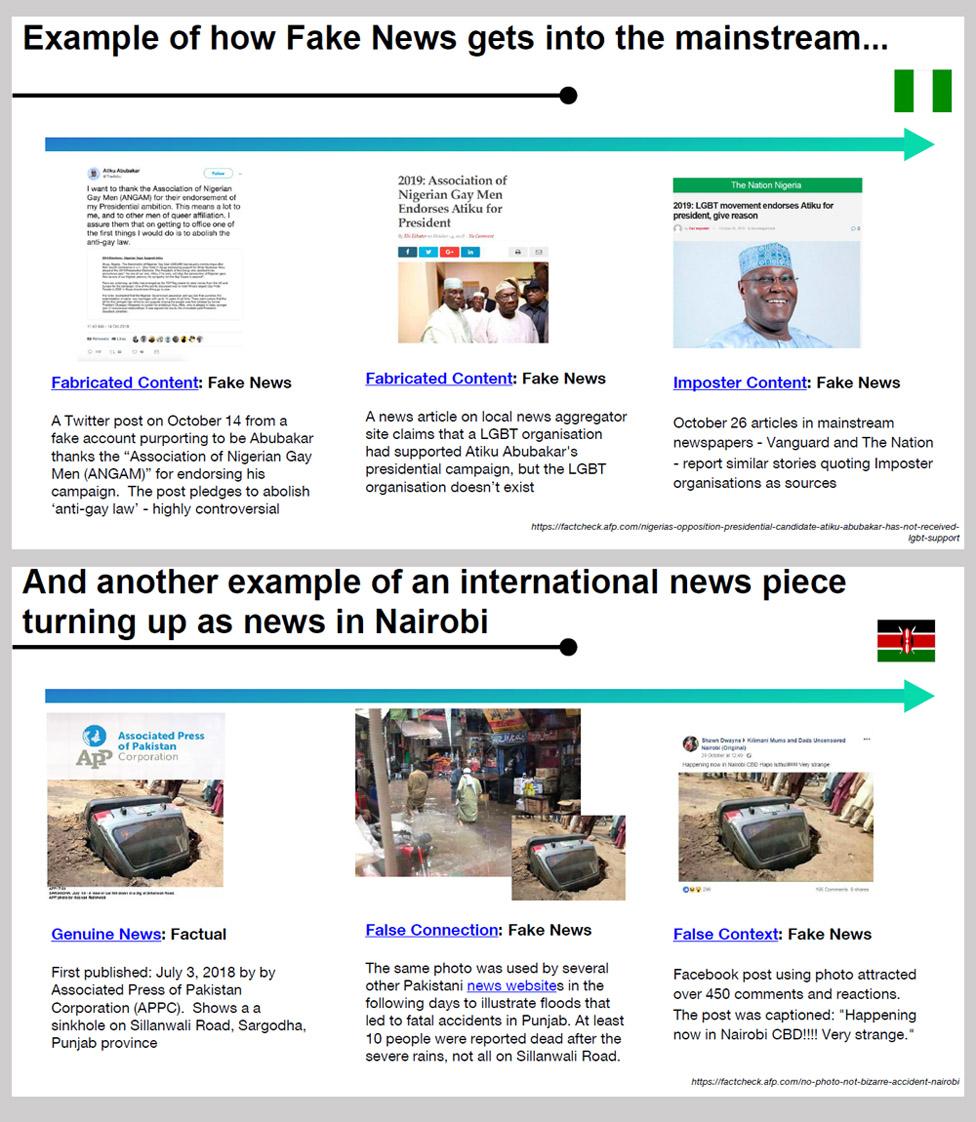

The researchers used two examples to illustrate the origin and spread of fake news:

A tweet saying that a gay rights association, which doesn't actually exist, had backed the election campaign of opposition leader Atiku Abubakar ended up being reported in mainstream newspapers in Nigeria

A photograph of a car falling into a sinkhole in Pakistan was copied by a Facebook user, saying it was in Nairobi

Verifying information can be difficult, which African fact-checkers say is because of the lack of reliable, accurate and independent data across a lot of sectors - which means manipulation of information is easier.

What fake news did the investigation find?

National anxieties and aspirations are often reflected in fake news messages.

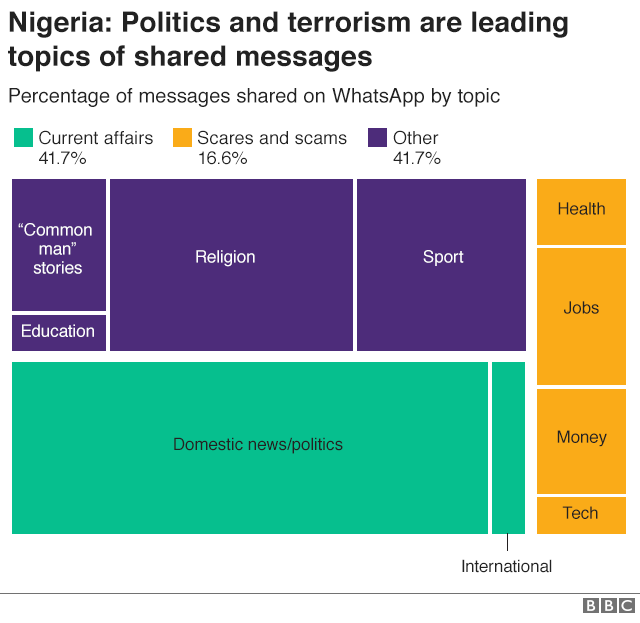

In Nigeria where almost 19% of people are jobless, employment scams make up 6.2% of fake news stories shared in WhatsApp.

Roughly 3% of fake news circulated on WhatsApp concerns terrorism and the army, mirroring Nigerians' anxieties about instability and uncertainty caused by Islamist militants among other things.

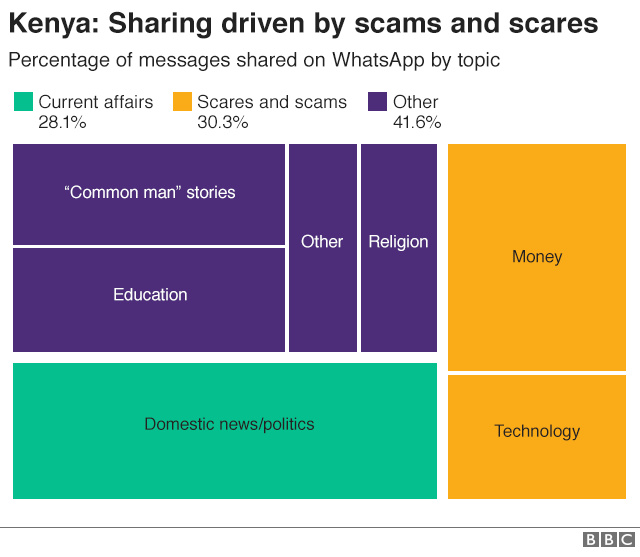

Scams related to money and technology contribute to about a third of the fake news stories shared in Kenyans' WhatsApp conversations. Religion accounts for roughly 8%, researchers found.

Facebook users frequently fail to distinguish between fake news content and legitimate news on their feeds, the BBC team found by analysing Facebook advertising data by users' interests.

How organised is the spread of misinformation on private and public networks?

Finding the answer to this question is the ultimate aim of BBC's Beyond Fake News project.

So far it has used big data to analyse 8,000 news articles in Kenya and Nigeria, analysed 3,000 Facebook pages and interests, conducted in-depth interviews with 40 individuals in both countries, and analysed a sample of more than 2,000 messages.

Kenyan and Nigerian social media users told the BBC they believe sensationalist and fake stories are being written on digital platforms purely to make money.

Sensationalist headlines used by parts of the mainstream journalistic sources, and the rush to publish without verification, are further blurring the lines between legitimate journalism and out-and-out misinformation.

Television news, however, is seen as harder to fake because it is not "faceless" and involves sophisticated production methods.