Ezekiel Mutua: The man who polices Kenyan pop music

- Published

Ezekiel Mutua has been dubbed Kenya's "moral policeman"

Kenya's "moral policeman" Ezekiel Mutua is at the centre of a new storm after banning two popular songs, but the ex-journalist relishes his role, writes the BBC's Ashley Lime from Nairobi.

When I met Mr Mutua the first things I noticed were his pencil-thin moustache and friendly smile.

The chief executive of the Kenya Film Classification Board (KFCB) warmly welcomed me into his office, but his charm belies his reputation as a stern "moral policeman" who censors films, songs, and television adverts which feature sexualised content and same-sex relationships.

A song with references to oral sex, adverts for a "sex party" and a film featuring a lesbian couple have all felt the force of Mr Mutua's action.

But the former journalist, who is a devout Christian, objects to being called a censor.

"Censorship connotes some dictatorial and colonial tendencies," Mr Mutua says.

He is more comfortable with the moniker "moral policeman", though it took him a while to embrace it.

In general, Kenya has a traditional and socially conservative culture, but this has been challenged in recent years by some in the younger generation.

This country need me, but it needs more people to act as moral champions"

The explosion in the use of social media has fuelled more open discussions about sex and relationships, and the arts have reflected this.

Mr Mutua is at the frontline of this culture clash.

"At first I was really offended when [critics] referred to me as moral policeman, but with time I realised that not only does this country need me, but it needs more people to act as moral champions," he said.

'Dirty and unsuitable'

At the helm of KFCB since 2015, he has often been at the centre of controversy, with Kenyans expressing mixed reactions to his directives.

The position gives him the power to rate and classify films and no film can be shown in Kenya without being classified.

He also believes that he has oversight over other audio-visual output on TV and online, but some dispute that his powers go that far.

In his latest move, on Tuesday, Mr Mutua banned two hit songs Wamlambez and Tetema from being played in public, except in clubs and bars.

In a Twitter post, he said the two songs were "pure pornography" and "dirty and unsuitable for mixed company".

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The lyrics for Wamlambez, released in April, are in Sheng, a slang used by young people across Kenya, and have metaphors alluding to oral sex.

The song, by Kenyan group Sailors, is so popular that the words "wamlambez" and "wamnyonyez" - a corruption of words meaning "lick" and "suck" - have become commonplace greetings among many young people.

The video, which has been viewed nearly four million times on YouTube, also features lewd dance moves.

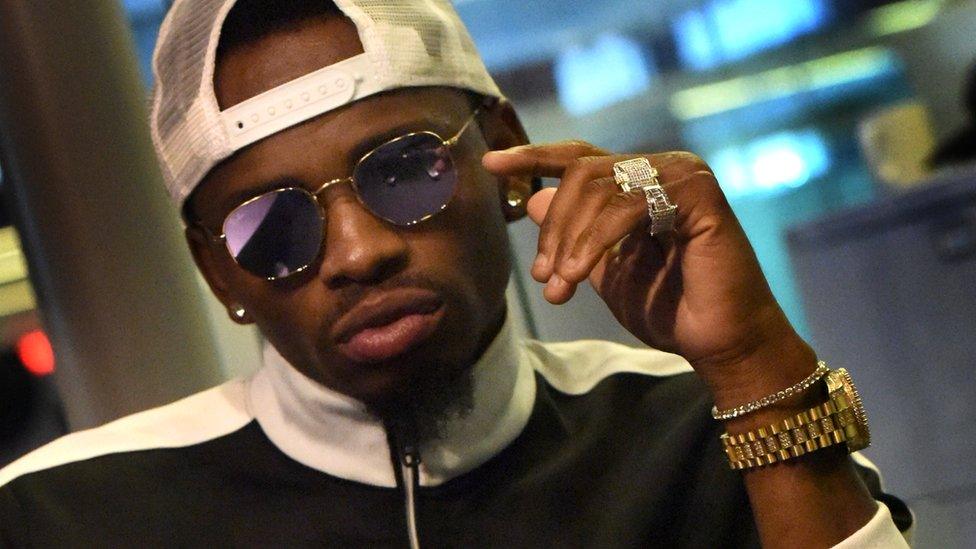

The lyrics of a song by Tanzanian artist Diamond Platnumz have been called "dirty" by Mr Mutua

Mr Mutua also criticised national leaders for singing and dancing "to the obscenity in public".

When it comes to Tetema (meaning "twerking" in Swahili), by Tanzanian artist Diamond Platnumz, Mr Mutua has described the lyrics as dirty.

The moral policeman has received both praise and criticism for his directive.

One commenter, backing the ban, said some songs were a "disgrace".

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

But a critic called Mr Mutua "annoying" and accused him of making "decisions for adults".

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Many of the ordinary people I spoke to in the capital, Nairobi, supported Mr Mutua's move. Some told me they thought he should have acted sooner given that children had already started singing the lyrics.

In April, he banned a song by local musician Alvin, who is popularly known as Alvindo, called Takataka (meaning "rubbish" in Swahili), saying it was an incitement to violence against women by "rejected" men.

'Demonic'

"The song Takataka is characterised by crude language that objectifies women and glorifies hurting them as a normal reaction to rejection," Mr Mutua said in a statement at the time.

But critics on social media said the move was akin to banning Romeo and Juliet for "glorifying murder and suicide".

Mr Mutua chided another local musician, Akothee, in February after pictures of her pulling raunchy stunts during a public performance went viral on social media.

He said the stunts were "filthy", "stupid" and "demonic".

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

In 2016, he banned a party after its organisers circulated publicity posters in Nairobi declaring "no one goes back home a virgin", and it would be "one night to lose your mind".

The party was organised so people could make and sell films of pornography and drug abuse, Mr Mutua said at the time.

Mr Mutua also outlawed a girls-only speed-dating party set to take place in Nairobi three years ago, saying its flier suggested the participants would be lesbians.

Despite the backlash, he is unrepentant about his decisions, saying children are given "weird" perceptions of life by people who "introduce things that are foreign to Kenya's culture and undermine the family unit by saying a man and another man can form a family".

He argues that central to his work is the protection of children from harmful content such as nudity, foul language, obscenity and violence.

Samantha Mugatsia and Sheila Munyiva play the film's young lovers, Kena and Ziki

Of the many decisions Mr Mutua has made, the one that raised his profile worldwide was when, in 2018, the KFCB banned the Kenyan film Rafiki, directed by Wanuri Kahiu.

The film, which was due to have its premiere at the Cannes Film Festival, depicts the story of two young women, Kena and Ziki, who meet and fall in love.

But the board said the film had been restricted over "its homosexual theme and clear intent to promote lesbianism in Kenya". Homosexual acts are illegal in Kenya and are punishable by 14 years in prison.

"That's not a movie that's going to define the film industry in this country - we don't allow gay content," maintains the film regulator.

When Rafiki was initially banned, the director tweeted she was "incredibly sad" that her film could not be legally watched in her home country.

But Mr Mutua says the decisions he makes are about faith, culture and morality, and that "offensive content" in films can fundamentally impact the culture of the country.

'Violating family values'

The list of other films that the KFCB has banned, including Wolf of Wall Street and Fifty Shades of Grey, underlines this message

Wolf of Wall Street was banned because of "extreme scenes of nudity, sex, alcohol, drug taking and profanity", the KFCB said

Television adverts are also subject to KFCB regulation, and in 2016 Coca Cola was forced to remove adverts featuring a kissing couple, which the film board said violated "family values".

The growth of the internet in Kenya, Mr Mutua says, has made his job difficult, and parents look to the board for guidance during long holidays.

Critics accuse the moral cop of overreaching his authority, but Mr Mutua says his decisions are based on the law and he has to apply the law.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

A lot of the backlash he gets, he adds, is based on a lack of understanding and what he sees as the breakdown of the moral fabric where people do not know the difference between right and wrong behaviour.

"There is so much noise from the public," says Mr Mutua.

"Those guys on social media are very few but they can make you feel as though the entire country is against you," .

And when Kenyans thought the moral policeman was on his way out at the end of his tenure last October, the directors at KFCB renewed his contract for three more years.

Role of religion

There has been a debate on Mr Mutua's powers, external, with some critics saying that it is not his role to censor music and protect children. But others praise him, saying he works hard and gets results.

In 2018, the state agency that oversees broadcasting criticised the KFCB for issuing guidelines on the airing of adverts, saying the board's mandate was limited to rating broadcast content and not controlling it.

However, Mr Mutua says the law empowers him to ban songs and even parties deemed immoral as enshrined in the Film and Stage Plays Act , external.

As a practising Christian, Mr Mutua is often criticised for using religious principles to help him make decisions.

But he says he makes no secret of who he is.

"I don't practise my faith under the carpet, I do it openly and it informs my decisions to a large extent."

He insists, however, that he does not "regulate using the Bible".

Mr Mutua says that while Kenya has become a liberal democracy, where freedom of expression is enshrined in the constitution, it does not mean that it should abandon its culture.

And he is prepared to police the frontline.

- Published4 July 2023

- Published13 October 2017

- Published22 March 2017