Zimbabwe's scaled-back Christmas celebrations

- Published

Most Zimbabweans have been unable to afford Christmas treats because of soaring inflation, writes the BBC's Shingai Nyoka from the capital, Harare.

Two women with large trolleys had come prepared to stock up for the holiday season, but they looked at each other in dismay.

"What kind of a party are we going to have?" one asked the other.

They were staring at a notice taped to the supermarket fridge door which said: "2 units per customer".

This was the drinks section of a shop in the centre of Harare, and the units referred to were the 300 millilitre bottles of soft drinks and beer.

The Christmas and New Year's holidays are usually a time for Zimbabweans to loosen their belts for feasts and celebrations.

The rationing of drinks has affected people's ability to hold parties

During the break the whole country shuts down. Factories close for the month, and the rains herald the start of the agricultural season.

Many Zimbabweans travel to their rural homes to see their extended family and to plant maize, to provide a year-long supply of the staple food.

On Christmas Day most people attend church, while throughout the season family gatherings are at the centre of the holidays.

Avoiding Christmas trimmings

This year, however, things are different, and belt-tightening is the order of the day.

The country is in the middle of an economic crisis.

At times, there have been long bank queues of people hoping to get hold of much-needed cash

According to the latest inflation figures, prices rose overall by 30% in the last year and each month that figure seems to be going up.

Supermarket shelves may be abundant with goodies but shoppers' trolleys are uncharacteristically sparse as they face the consequences of rising prices.

The chicken that just over a year ago cost $3.50 (£2.76) is now priced at $7.19, while the price of 400g of muesli has risen from $5 to $12 and a pack of nine rolls of toilet paper has gone up from $8 to $19.

Salaries, however, have not kept up with inflation. In fact, the average wage of $300 a month is the same as it was a year ago.

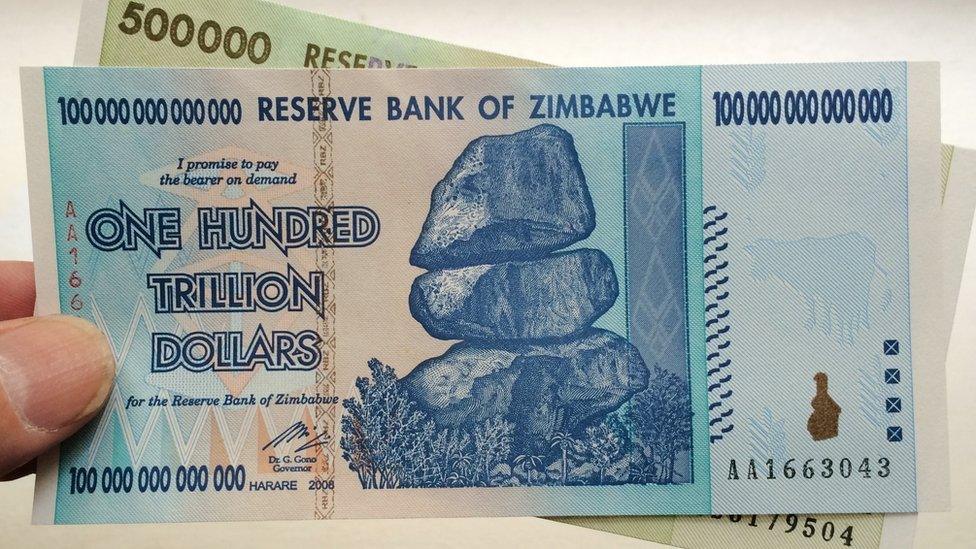

Zimbabweans have held a series of protests to show their money has become worthless

Given that, the trimmings that can give a meal an extra sparkle might be avoided.

For example, an ordinary pack of 12 Christmas crackers with a joke, a hat and a small gift is selling at $40, compared to less than $15 last year.

Parties cancelled

It explains perhaps why some party invitations have been withdrawn and planned celebrations have been scaled back.

One businessman told me that he had to cancel his usual holiday party and turn it into a more abstemious lunch, thereby removing the burden of having to buy lots of drinks.

Back at the supermarket, a man was standing in an aisle next to shelves of rice, carefully comparing prices and products.

His eye rested on an unfamiliar product, Broken Rice.

Broken Rice is made up of pieces of rejected rice

The 2kg package was priced $4.69 and was the cheapest brand available.

"Broken" is a euphemism for tiny imperfect pieces of rejected rice.

It had been packaged in time for the festive season, where no meal is complete without chicken and rice, an imported luxury.

'More suffering in post-Mugabe era'

In a way the broken rice is a metaphor for the season, which feels imperfect.

"I started seeing it in the shops about a month ago," the man, who introduced himself as Shupi, told me.

"We are used to having rice at Christmas. It is supposed to be a treat but it has become so expensive.

"Initially, people had shunned this rice because it is in small pieces and in different sizes. Some complain it doesn't cook evenly, but at least it is affordable."

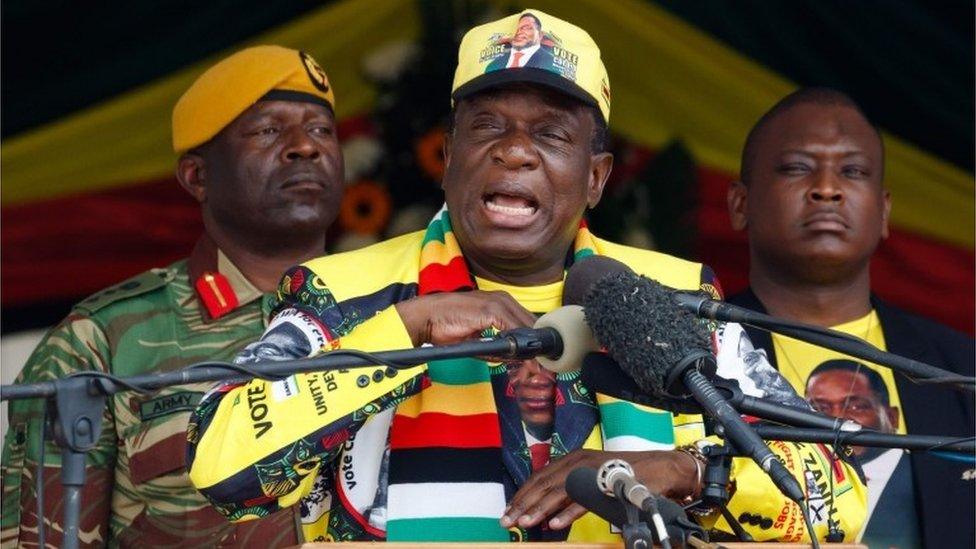

Discontent with President Emmerson Mnangagwa's government is growing

Many, like Shupi, remember the promises made when President Emmerson Mnangagwa swept to power in November 2017 after Robert Mugabe was ousted.

"He promised us better years ahead and blamed our suffering on years of being under Robert Mugabe.

"But he has been in power for more than a year and the crisis has gotten worse," Shupi added.

Runaway inflation

Zimbabweans have endured much over the last decade.

Ten years ago, supermarket shelves were mostly empty and record-breaking inflation was estimated to have topped 79 billion %.

It meant that prices for basic commodities would double or triple in a day, and bank balances for ordinary people could range from trillions of Zimbabwean dollars to octillions, that is a one followed by 48 zeros.

In 2009 the government scrapped the local currency and adopted the US dollar.

President Emmerson Mnangagwa took power in November 2017 with a promise to improve the economy

Then, in 2016, in order to get over a shortage of physical cash, the authorities introduced a surrogate note, known as a bond note, that was supposed to have the same value as the US dollar.

In other words, a two-dollar bond note was supposed to be worth $2.

But the bond notes, or "bollars", have lost value because of a lack of foreign currency backing the note. They are now worth 30 US cents each on the black market.

Zimbabwean companies are not producing enough to satisfy local demand or to earn foreign currency by exporting goods. Instead, the country is importing more, and struggling to pay.

You may also like:

In the six months from February to July this year, the country brought in goods and services worth $3.43bn, a 26% rise for the same period in 2017.

Driving the imports are the demand for fuel, electricity, soya beans, rice and wheat.

Businesses that want to import goods have been forced to buy US dollars on the black market at a premium price. This in turn pushes up the prices in the shops.

In order to increase its stock of hard currency, the country's largest fast food franchise, Simbisa Brands, announced last Thursday that it had introduced a two-tier pricing model, offering discounts to customers who pay in US dollar notes.

'Give us your cash'

"We need something like $1.2m in hard currency every month, but on average we are only managing to get about $100,000, so we need the foreign currency to meet our obligations.

"We are simply asking our clients to be able to support to get the forex we need," chief executive Warren Meares told local daily paper Newsday.

But not everyone is complaining.

People transporting goods across the border are doing a roaring trade

The Beitbridge border post which connects Zimbabwe to South Africa is the busiest in the region, and Christmas is the busiest period of them all.

Cars, pick-up trucks, lorries and buses are laden with groceries from South Africa ready to be delivered to Zimbabwean homes.

The cross-border traders known as Malayitshas - meaning "one who carries goods" in the Ndebele language - have been among the biggest beneficiaries of the crisis.

They offer a courier service for those with foreign currency. They buy goods - anything from soft drinks to building materials - across the border and deliver them for a fee of 30% of the value.

'Austerity for prosperity'

In Musina, on the South African side of the border, business is picking up and small Indian and Chinese-owned shops are coming back to life.

Many had closed in 2009 when the economy began to improve, but they have recently reopened as the prices have spiked in Zimbabwe.

Many shopkeepers say business has been bad this Christmas

Despite the Christmas woes Finance Minister Mthuli Ncube has expressed confidence in the future of the economy.

He says it is "just a matter of time" before the country is "restored to its glory days".

Zimbabwe was once the breadbasket of southern Africa feeding its neighbours and providing economic refuge and jobs in times of crises.

The government has now introduced what it calls "austerity for prosperity" measures. These include lowering government expenditure while increasing duty on items such as cars to reduce imports.

The optimism is not shared by those whose Christmas meal will consist of reject rice and miniscule portions of chicken washed down with small amounts of drink.

- Published26 July 2018

- Published25 July 2018

- Published12 October 2018

- Published4 August 2018

- Published22 November 2017