Kenya attack: 'Our deaths are displayed for consumption'

- Published

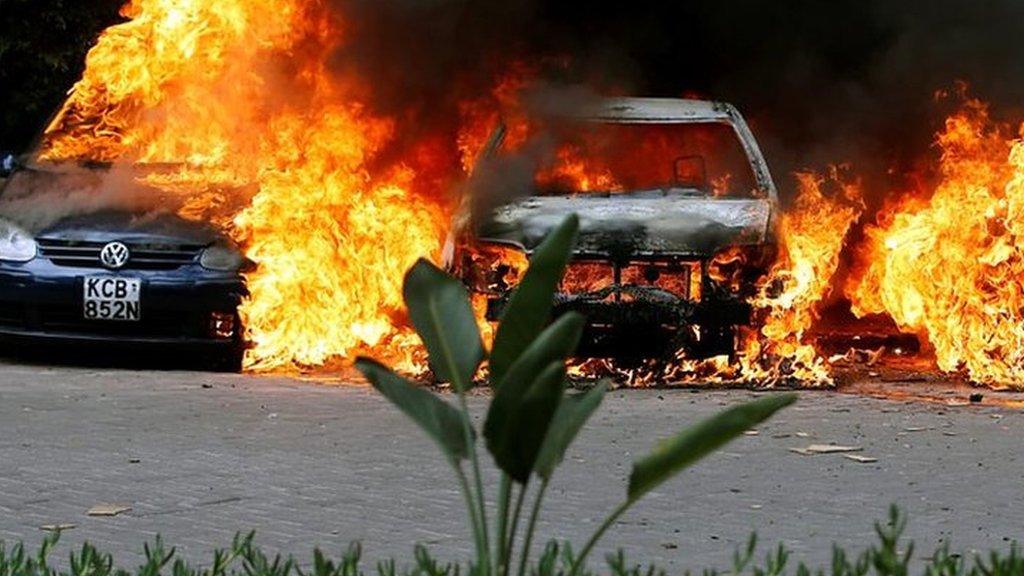

The attack on the Dusit hotel left at least 14 people dead

The attack wasn't over when the picture of the dead men slumped over the tables in the Nairobi restaurant where they had been having lunch was published.

The decision of a number of US and European outlets - including the UK's MailOnline and Germany's Bild - to use the photograph was instantly condemned on Kenyan social media. The New York Times came in for the most criticism. The newspaper, angry users said, was using the "misery and tragedy" of Tuesday's terror attack on the Dusit hotel for clickbait.

What's more, the speed with which the picture was published meant many were still unaware their loved ones had been caught up in the attack.

"Let me break [it] down," Jennifer Kaberi wrote in a tweet to the newspaper. "A friend of mine is at this hour (midnight) looking for her nephew who works in that building.

"Imagine she sees those photos."

It is not the first time pictures of bodies from an atrocity have been published. But the Kenyan photograph's publication raises questions over what should, and should not, be published - and whether outlets play by different rules when it comes to African victims.

Nairobi Dusit hotel attack: explosions, gunfire and rescue operation

Many outlets - including the BBC - have strict rules on what pictures they can and cannot publish.

"Images portraying dead or dying humans" can only be used "with special care and with editorial justification", BBC guidelines say. In practice, it means photos of the dead and dying are used extremely rarely.

The Media Council of Kenya, meanwhile, advises "publication of photographs showing mutilated bodies, bloody incidents and abhorrent scenes shall be avoided" unless in the public interest.

And sometimes, newspapers argue, a graphic image is needed to expose the realities of war, or terror, or - in the case of a little boy lying dead on a beach - highlight the plight of a people trying desperately to reach safety.

The picture of five-year-old Alan Kurdi still stands out in many people's minds as the moment they truly understood the enormity of the migrant crisis. The UK's Independent newspaper went as far as to publish the image in full on its front page.

"It was not an easy decision," the paper's deputy managing editor, Will Gore, told the BBC at the time. "But our view was that this image was clearly something of a different order to images we'd seen before, and came at a time when the debate about what to do seemed to be getting nowhere."

The photo, Gore argued, was the best image if they "were going to show the real horror of what happened to him".

Many pictures showed people running for their lives

Joseph Kariuki, former digital editor of Kenyan newspaper The Star, has also made the decision to publish distressing images in the past - even when he knew there was likely to be a public backlash.

On one occasion, it meant showing a picture of a mother who had been killed with her baby strapped to her back during ethnic clashes in the east of the country.

"That week over a hundred people had been killed and then that picture of the mother and her baby surfaced," he recalled.

"We had to show the public what was happening."

It had results, he said, in so far as "for the first time, the president spoke about the clashes and ordered more boots on the ground".

But publishing the images from the attack in Nairobi, he argued, had no such public interest defence, showing the impact or frequency of the attacks.

"In my view, they were not justified to use those pictures considering the last time we had a terror attack was more than two years ago and the impact is much less compared to Garissa University attack [where 148 people died] or Westgate [Mall attack, where 67 died]."

But The New York Times has said it does have a justification in printing the pictures.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

"We want to be respectful to victims and to others affected by the attack," the newspaper wrote in a statement. "But we also believe it is important to give our readers a clear picture of the horror of an attack like this. This includes showing pictures that are not sensationalised but that give a real sense of the situation."

The approach, the statement concluded, was used "wherever in the world something like this happens".

But, Kenyans argued, most of the time, that isn't the case when it comes to US victims. On the other hand, photographs of African victims are more commonplace.

"African victims of atrocities such as yesterday often get their death displayed for consumption with little to no regard for their privacy or the grief of their family members," James Siguru Wahutu, a fellow at BKC Harvard who studies media and mass atrocities, said.

"What makes the images even more egregious is the fact that the event was still unfolding and people were looking for their loved ones. This would never happen during a mass shooting or terror event in the US.

"So while NYT hides behind its editorial standards when challenged by Kenyans, it is also true that they have been reticent in displaying dead Americans in their coverage of atrocity.

"So why not extend the same courtesy to Africans?"

The BBC has approached the New York Times for comment.

- Published31 May 2018

- Published4 September 2015

- Published16 January 2019

- Published14 January 2019

- Published16 January 2019

- Published15 January 2019

- Published22 December 2017

- Published4 July 2023