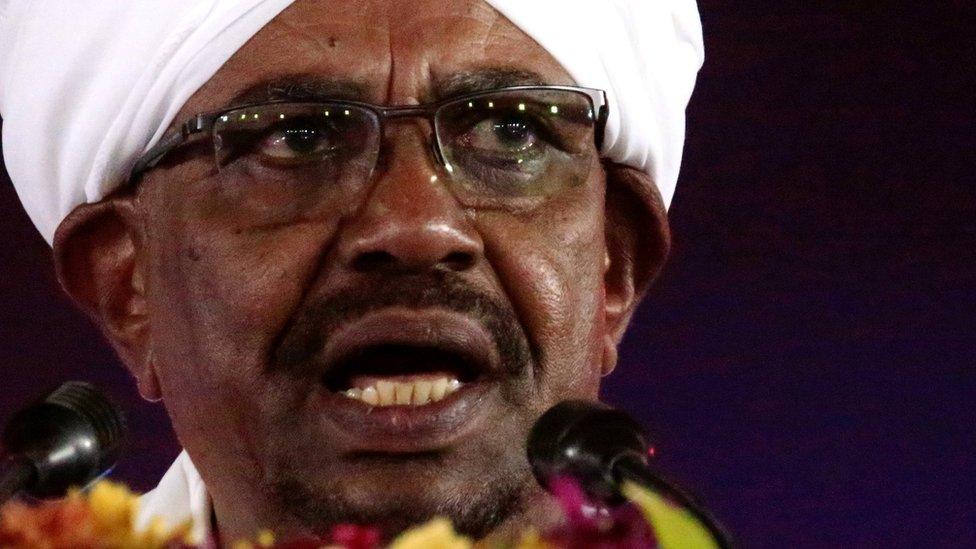

Bashir's state of emergency fails to end Sudan protests

- Published

Protest organisers have vowed to continue with daily rallies

Sudan's President Omar Hassan al-Bashir declared a state of emergency on Friday in an attempt to end a 10-week uprising that has threatened to bring an end to his 30 years in power.

However, if anything, the protests have gathered momentum since his declaration and on Monday, he banned protests and public gatherings, according to Reuters news agency.

What has happened since the announcement?

Mr Bashir's declaration was widely anticipated and protesters had already taken to the streets before his speech on Friday, and continued as he was speaking.

Since then, the protests have increased with thousands of demonstrators in the capital Khartoum and Omdurman, its twin city across the River Nile.

The opposition Umma National party and the protest organisers, the Sudanese Professionals' Association, have both rejected the new measures and called for more protests to force Mr Bashir to step down.

The security forces have resumed firing live ammunition at protesters, according to opposition sources. They say three people were injured with gunshot wounds on Sunday.

In hotspots such as the Khartoum district of Burri, door-to-door searches for activists and protesters have been carried out.

What happens inside Sudan’s secret detention centres?

What did Bashir announce?

The embattled president declared a national state of emergency across the country to last for up to one year.

He dissolved the government after just over five months in office and sacked his long-time ally - the only remaining member of the original Revolutionary Command Council that carried out the coup which brought him to power in 1989 - Gen Bakri Hasan Salih as vice-president.

But he was replaced with another hardliner, the Defence Minister, Gen Awad Ibn Awof, who has been under US sanctions since 2006 for his alleged role in Darfur, when he was the chief of military intelligence.

President Bashir also dissolved all elected regional governments and replaced all state governors with senior military officials.

In addition to banning public protests on Monday, he also announced further regulations on transporting foreign currency and gold, and a ban on hoarding or trading fuel products, Reuters reports.

What did he not say?

There had been speculation that President Bashir would say he not running for another term and also that he would step down as head of the ruling National Congress Party (NCP). However, he did neither.

His resignation as president is the key demand of the ongoing anti-government demonstrations which started in mid-December.

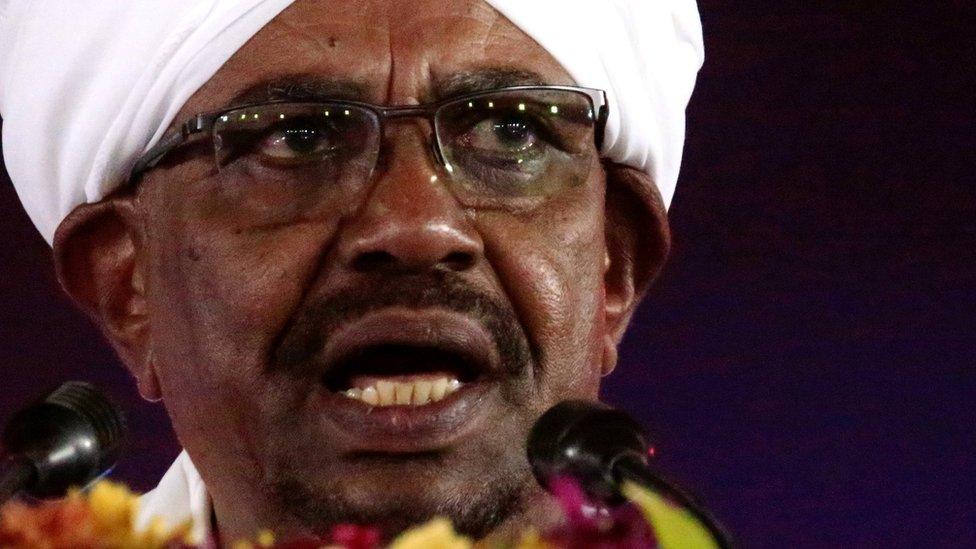

There had been speculation that Mr Bashir would say he was not seeking re-election

Mr Bashir did try to distance himself from the NCP by announcing that he would "stand at an equal distance from all the political forces", and most of the governors he sacked were from the ruling party.

Some Sudan observers have likened this moment to the infamous split between Mr Bashir and his Islamist "godfather", the late Hassan al-Turabi in 1999.

Back then, Mr Bashir dissolved parliament, suspended the constitution and split Sudan's Islamists between the National Congress and the Popular Congress parties.

On Monday, Sudanese press statements attributed to senior NCP figures suggest that the party will consider electing a new party head.

One senior regime stalwart, Amin Hassan Omar, told the Sudanese daily al-Intibaha that the president had consolidated all powers in his hands and the party could not be seen to be running the country.

But it is not yet clear whether Mr Bashir and the NCP will have a permanent split, as happened in 1999, or if it is just tactical manoeuvring.

What difference does the state of emergency make?

Since the state of emergency was declared, hundreds of pick-up trucks with mounted machine guns have been deployed onto Khartoum's streets, along with armoured personnel carriers. The pick-up trucks are known locally as Thatchers, after the former British prime minister - a reference to their agility and toughness.

A show of force on this scale was last seen at the end of December.

Activists and protesters have ridiculed the declaration of a state of emergency with all the extra powers it gives the security forces.

They have pointed out that, as far as they are concerned, they have already been living under a state of emergency where the authorities use force with impunity, arrest people without warrants and detain them without investigation.

- Published31 January 2019

- Published27 January 2019