Is Mansa Musa the richest man who ever lived?

- Published

Mansa Musa travelled to Mecca with a caravan of 60,000 men and 12,000 slaves

Amazon founder Jeff Bezos is the richest man in the world, according to the 2019 Forbes billionaires' list released this week. With an estimated fortune of $131bn (£99bn) he is the wealthiest man in modern history.

But he is by no means the richest man of all time.

That title is believed to belong to Mansa Musa, the 14th Century West African ruler who was so rich his generous handouts wrecked an entire country's economy.

"Contemporary accounts of Musa's wealth are so breathless that it's almost impossible to get a sense of just how wealthy and powerful he truly was," Rudolph Butch Ware, associate professor of history at the University of California, told the BBC.

Mansa Musa was "richer than anyone could describe", Jacob Davidson wrote about the African king for Money.com in 2015.

In 2012, US website Celebrity Net Worth estimated his wealth at $400bn, external, but economic historians agree that his wealth is impossible to pin down to a number.

The 10 richest men of all time

Mansa Musa (1280-1337, king of the Mali empire) wealth indescribable

Augustus Caesar (63 BC-14 AD, Roman emperor) $4.6tn (£3.5tn)

Zhao Xu (1048-1085, emperor Shenzong of Song in China) wealth incalculable

Akbar I (1542-1605, emperor of India's Mughal dynasty) wealth incalculable

Andrew Carnegie (1835-1919, Scottish-American industrialist) $372bn

John D Rockefeller (1839-1937) American business magnate) $341bn

Nikolai Alexandrovich Romanov (1868-1918, Tsar of Russia) $300bn

Mir Osman Ali Khan ( 1886-1967, Indian royal) $230bn

William The Conqueror (1028-1087) $229.5bn

Muammar Gaddafi (1942-2011, long-time ruler of Libya) $200bn

Source: Money.com, Celebrity Net Worth

The golden king

Mansa Musa was born in 1280 into a family of rulers. His brother, Mansa Abu-Bakr, ruled the empire until 1312, when he abdicated to go on an expedition.

According to 14th Century Syrian historian Shibab al-Umari, Abu-Bakr was obsessed with the Atlantic Ocean and what lay beyond it. He reportedly embarked on an expedition with a fleet of 2,000 ships and thousands of men, women and slaves. They sailed off, never to return.

Some, like the late American historian Ivan Van Sertima, entertain the idea that they reached South America. But there is no evidence of this.

In any case, Mansa Musa inherited the kingdom he left behind.

Under his rule, the kingdom of Mali grew significantly. He annexed 24 cities, including Timbuktu.

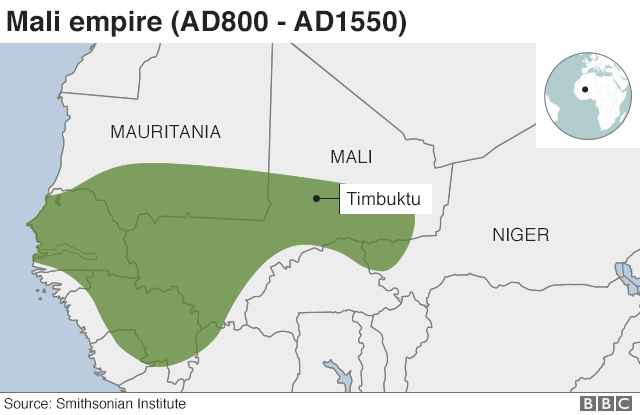

The kingdom stretched for about 2,000 miles, from the Atlantic Ocean all the way to modern-day Niger, taking in parts of what are now Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, The Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea and Ivory Coast.

With such a large land mass came great resources such as gold and salt.

During the reign of Mansa Musa, the empire of Mali accounted for almost half of the Old World's gold, according to the British Museum.

And all of it belonged to the king.

"As the ruler, Mansa Musa had almost unlimited access to the most highly valued source of wealth in the medieval world," Kathleen Bickford Berzock, who specializes in African art at the Block Museum of Art at the Northwestern University, told the BBC.

"Major trading centres that traded in gold and other goods were also in his territory, and he garnered wealth from this trade," she added.

You might also like:

The journey to Mecca

Though the empire of Mali was home to so much gold, the kingdom itself was not well known.

This changed when Mansa Musa, a devout Muslim, decided to go on a pilgrimage to Mecca, passing through the Sahara Desert and Egypt.

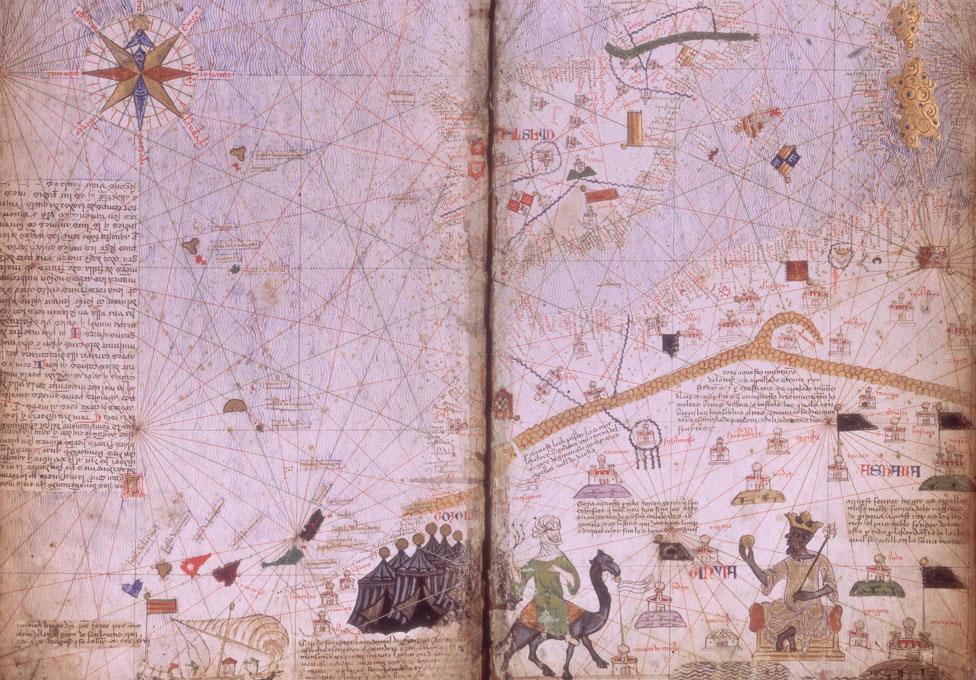

The trip to Mecca helped put Mali and Mansa Musa on the map - a photocopy of the Catalan Atlas map from 1375

The king reportedly left Mali with a caravan of 60,000 men.

He took his entire royal court and officials, soldiers, griots (entertainers), merchants, camel drivers and 12,000 slaves, as well as a long train of goats and sheep for food.

It was a city moving through the desert.

A city whose inhabitants, all the way down to the slaves, were clad in gold brocade and finest Persian silk. A hundred camels were in tow, each camel carrying hundreds of pounds of pure gold.

It was a sight to behold.

And the sight got even more opulent once the caravan reached Cairo, where they could really show off their wealth.

The Cairo gold crash

Mansa Musa left such a memorable impression on Cairo that al-Umari, who visited the city 12 years after the Malian king, recounted how highly the people of Cairo were speaking of him.

So lavishly did he hand out gold in Cairo that his three-month stay caused the price of gold to plummet in the region for 10 years, wrecking the economy.

US-based technology company SmartAsset.com estimates that due to the depreciation of gold, Mansa Musa's pilgrimage led to about $1.5bn (£1.1bn) of economic losses across the Middle East.

On his way back home, Mansa Musa passed through Egypt again, and according to some, tried to help the country's economy by removing some of the gold from circulation by borrowing it back at extortionate interest rates from Egyptian lenders. Others say he spent so much that he ran out of gold.

Lucy Duran of the School of African and Oriental Studies in London notes that Malian griots, who are singing historian storytellers, in particular, were upset with him.

"He gave out so much Malian gold along the way that jelis [griots] don't like to praise him in their songs because they think he wasted local resources outside the empire," she said.

Education at heart

There is no doubt that Mansa Musa spent, or wasted, a lot of gold during his pilgrimage. But it was this excessive generosity that also caught the eyes of the world.

Mansa Musa had put Mali and himself on the map, quite literally. In a Catalan Atlas map from 1375, a drawing of an African king sits on a golden throne atop Timbuktu, holding a piece of gold in his hand.

Timbuktu became an African El Dorado and people came from near and far to have a glimpse.

In the 19th Century, it still had a mythical status as a lost city of gold at the edge of the world, a beacon for both European fortune hunters and explorers, and this was largely down to the exploits of Mansa Musa 500 years earlier.

Mansa Musa commissioned the famous Djinguereber Mosque in 1327

Mansa Musa returned from Mecca with several Islamic scholars, including direct descendants of the prophet Muhammad and an Andalusian poet and architect by the name of Abu Es Haq es Saheli, who is widely credited with designing the famous Djinguereber mosque.

The king reportedly paid the poet 200 kg (440lb) in gold, which in today's money would be $8.2m (£6.3m).

In addition to encouraging the arts and architecture, he also funded literature and built schools, libraries and mosques. Timbuktu soon became a centre of education and people travelled from around the world to study at what would become the Sankore University.

The rich king is often credited with starting the tradition of education in West Africa, although the story of his empire largely remains little known outside West Africa.

"History is written by victors," according to Britain's World War II Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

After Mansa Musa died in 1337, aged 57, the empire was inherited by his sons who could not hold the empire together. The smaller states broke off and the empire crumbled.

The later arrival of Europeans in the region was the final nail in the empire's coffin.

"The history of the medieval period is still largely seen only as a Western history," says Lisa Corrin Graziose, director of the Block Museum of Art, explaining why the story of Mansa Musa is not widely known.

"Had Europeans arrived in significant numbers in Musa's time, with Mali at the height of its military and economic power instead of a couple hundred years later, things almost certainly would have been different," says Mr Ware.

- Published13 May 2018

- Published5 March 2019