Brexit: Will it affect the Kenyan flower trade?

- Published

As Britain prepares to leave the European Union, workers in Kenya's flower industry are closely monitoring developments.

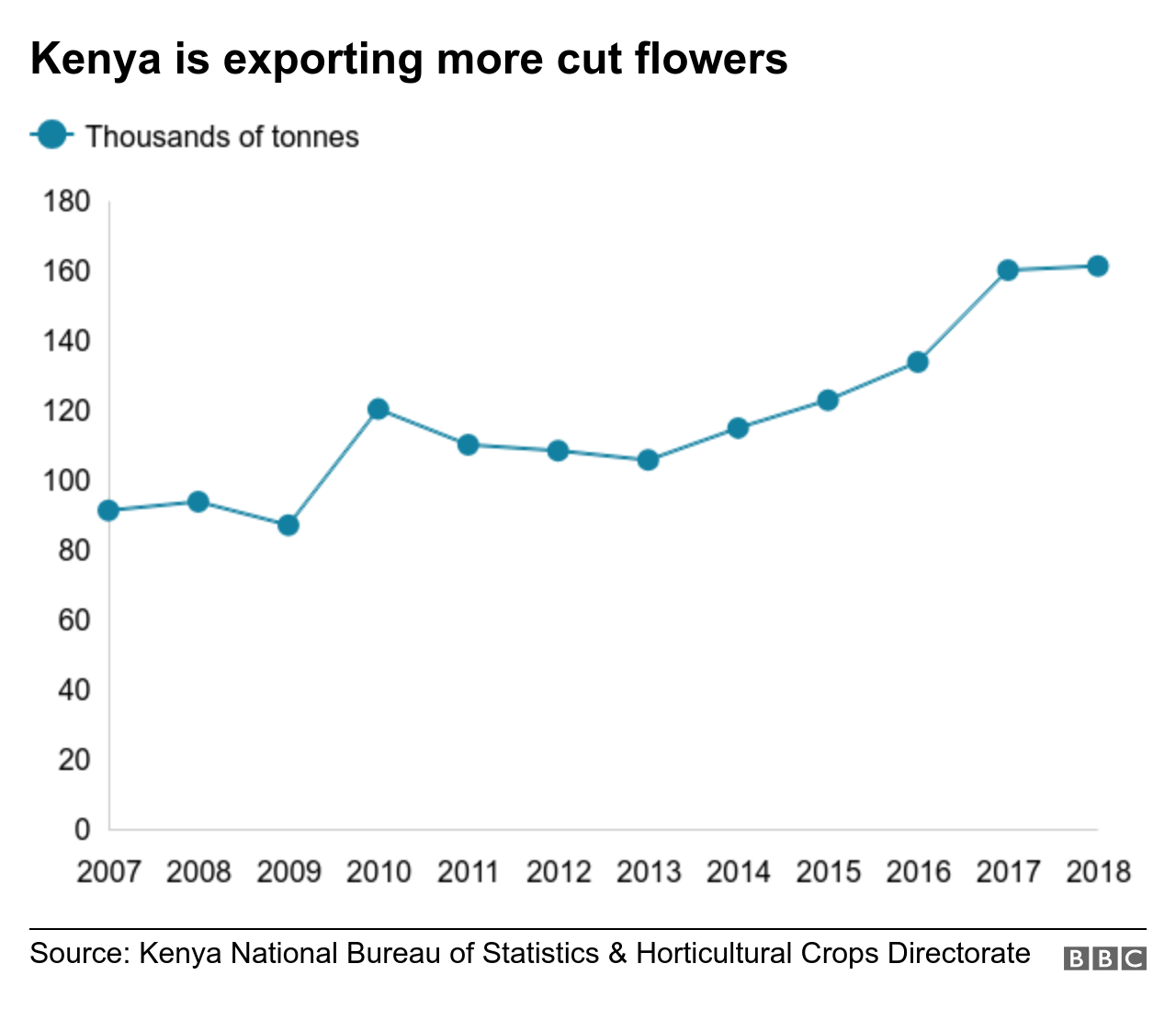

Flowers are big business in Kenya and earnings from exports have doubled in the past five years.

A key export destination is the UK, which most of the flowers enter after being auctioned in the Netherlands.

Growers and exporters in Kenya are asking the same question - what impact will Brexit have on the flower trade?

What is the current situation?

Kenyan flower exporters currently enjoy zero tariffs on cut flowers sold to the EU.

This is set by an interim arrangement, which Kenya secured through signing and ratifying the Economic Partnership Agreement between the EU and the East African Community.

The deal is temporary until the three other members in the regional group sign up so it can come into full effect.

Other major Kenyan exports such as tea, fruit and vegetables enjoy the same terms.

The Netherlands is a major transit point for Kenyan flowers entering Europe

Why does the UK flower trade matter to Kenya?

Britain is the second largest export destination for Kenya's cut flowers after the Netherlands, taking almost 18% of the flowers produced in the country.

The industry accounts for about 1.06% to Kenya's gross domestic product (GDP) - the total value of all the goods and services produced - according to the Flower Council.

It is also one of the largest employers in the country, providing jobs to more than 100,000 people directly and an estimated two million indirectly.

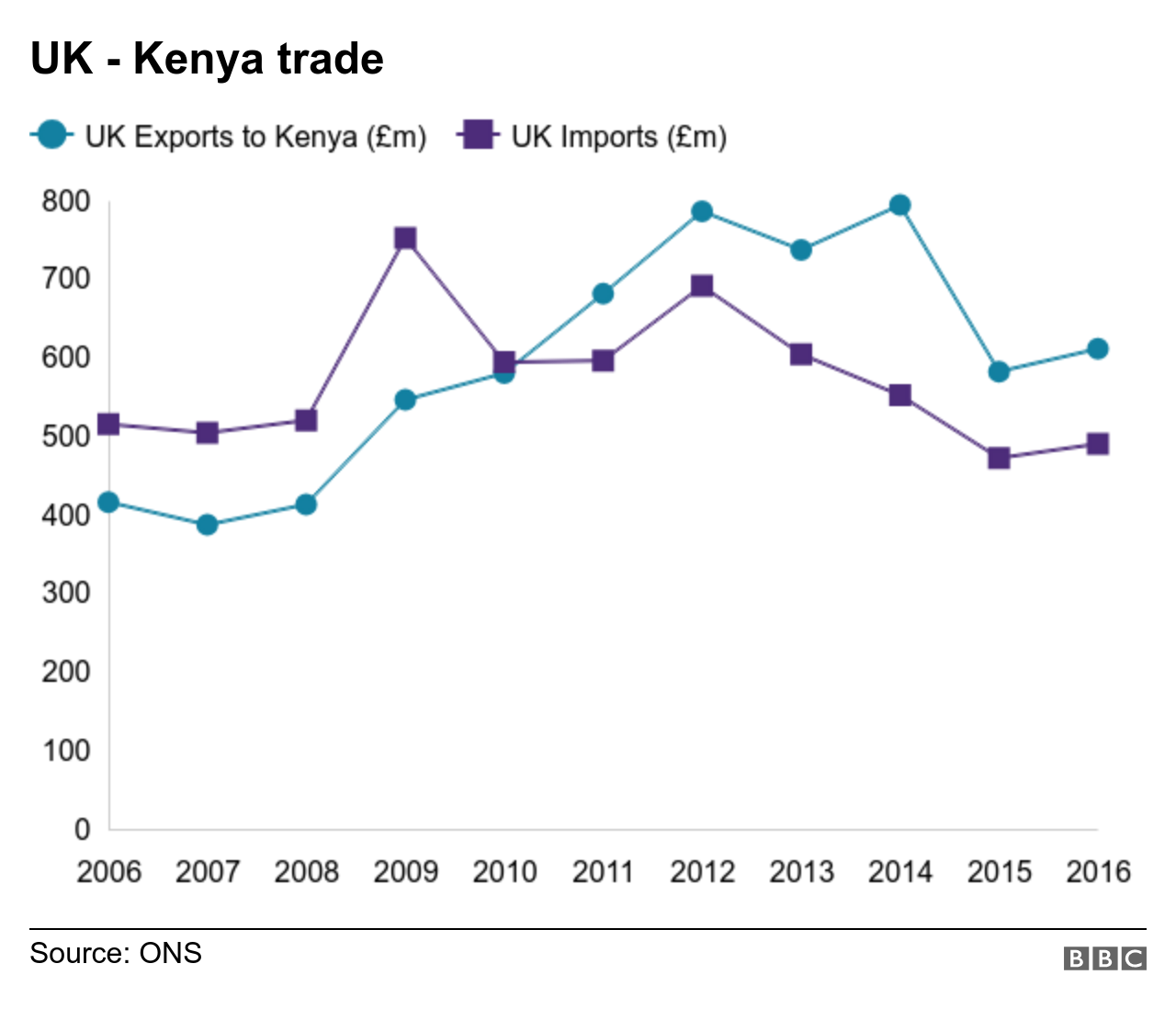

And although Britain remains a major trading partner for Kenya, overall trade between the two countries has been falling over the past few years.

Why worry about Brexit?

Kenya Flower Council chief executive Clement Tulezi said the infrastructure for handling flowers flown directly to the UK was not well developed, which left Amsterdam and Liege, in Belgium, as the most important entry points for flowers into Europe,

So, Kenyan flower-sellers are hoping the UK signs a deal with the EU before officially leaving on 29 March.

The deal proposed by the UK government would trigger a transition period that extends until 2020.

And during the transition period, Kenya would continue accessing the UK market as it does now while a future trade deal was negotiated.

This is what the Kenyan government is banking on.

Kenya's principal secretary in charge of trade, Chris Kiptoo, told BBC News: "We have all along got that assurance of no market disruption because of the fact that there will be an interim period up to 2020 December in which the UK will be operating under the EU law.

"Without a deal, it will not be just us, it will be everybody who has been trading with the UK. Everybody must find a way of trading with them."

A UK government official said: "The EU has temporary trade arrangements for Kenya and we intend to maintain the same level of access to retain Kenya's duty-free, quota-free access to the UK market."

During her visit to Kenya last year, Prime Minister Theresa May also said it would continue enjoying access to UK markets through the current duty free arrangement even after Brexit, before a new framework of trade is in place.

"Once we are outside the EU, we will have the opportunity to negotiate these trade deals on behalf of the UK rather than as part of the EU," she added.

The flower industry is one of the largest employers in the country, providing employment to more than 100,000 people

What about a no-deal Brexit?

Despite these assurances, there are concerns inside Kenya about what happens if the UK leaves without a deal.

The British government says it wants to replicate all the existing trade deals the EU has, with more than 70 countries, which the UK would lose in the event of leaving without a deal.

But in Africa, the UK government had by 21 February signed continuity deals only with member countries of the Eastern and Southern Africa (ESA) region, which covers Madagascar, Mauritius, Seychelles and Zimbabwe.

Without a trade deal in place for Kenya, the UK would have to set tariffs according to rules set by the World Trade Organization (WTO).

And Traidcraft Exchange and the Fairtrade Foundation say Kenya could face WTO tariffs of 8.5-12%, costing its flower exporters up to £3.6m annually.

This, say the charities in a joint report, "would undermine competitiveness in an already stressed supply chain" and would greatly affect revenue and workers' livelihoods.

There are also concerns over potential customs delays between the EU and UK for a product with critical delivery schedules.

Kenyan-based development economist Anzetse Were said a no-deal Brexit could see traders having to establish new distribution channels or use agents to sell the flowers in the UK.

"It will be work and money that they will have to spend figuring out how to reconfigure those supply chains that used to work seamlessly when everybody was united in one common market," she said.

Longer term, charities fear the UK may give priority to striking free trade agreements (FTAs) with richer countries, because of higher trade volumes.

But economically vulnerable countries, say the charities, need to know they will continue to be supported in trading their way out of poverty.